A Greek Cognate to Ægir's Wife Rán

An Original Theory by Carla O'Harris

with research help from Siegfried Goodfellow

[Main][Home]

|

|

||

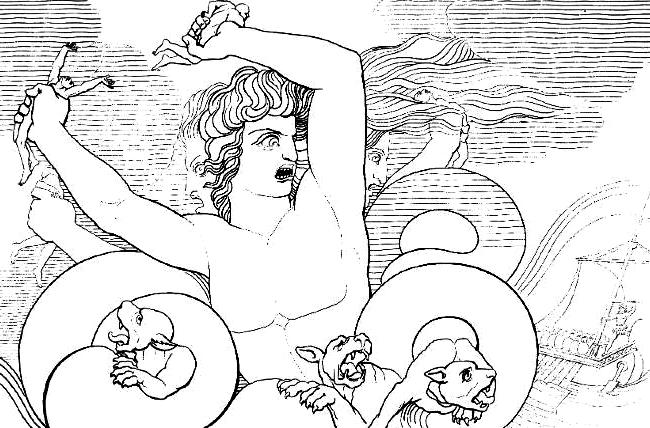

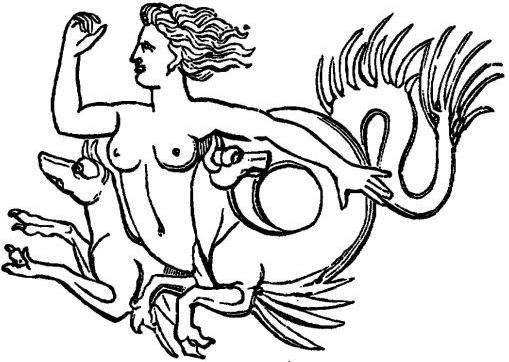

| Skilla from a Greek Coin | Ran and the Wave-maidens |

| Did Ægir's Wife Rán Have a Cognate in Greek Mythology? | |||||

It is here where we find Rán's cognate, because very close to Charbydis, the maelstrom-whirlpool, was a monster the Greeks called Skylla, and she fulfills a function very close to that of Rán. Our source for Scylla is Theoi.com, the most scholarly and reliable resource for Greek mythology on the web. Their article begins, “SKYLLA (or Scylla) was a monstrous sea goddess who haunted the rocks of a certain narrow strait opposite the whirlpool daemon Kharybdis.” Sailors who sailed too close would be devoured by her. Already we have a sea goddess who is monstrous, who is a threat to sailors, and who is found near the maelstrom. This fits Rán. But there is much more. One of the most striking features of Skylla is her imagery. Most often imagined from the waist up as an ordinary if striking woman, from the waist down, her iconography veers into the bizarre, for there, part of her body is either part fish or part serpent, with long serpentine tentacles, and part ferocious dogs. In other words, iconographically, she is associated (or even blended in the picture) with snakes and dogs or wolves. The reason this is significant is because Rán, as Angrboda, is the "Mother of three monsters": i.e. the World-Serpent, the Fenris Wolf, and her other child, Hel, who is monstrous on one half and human on the other half. Here we find Skylla with all three attributes. Although she is depicted as a chimeric monster with wolves and serpents parts of her body, we may understand this iconography as simply a clinging to her of motifs found deeper in the Indo-European strata.

As Gullveig-Heid, the Æsir repeatedly try to destroy Rán by fire, but each time she is reborn. "Thrice burnt and thrice reborn. Yet she lives!' declares Völuspá. When Odysseus asks Circe about Scilla, Homer puts these words into Circe's mouth (tr. Robert Fitzgerald) : “That nightmare cannot die, being eternal / evil itself – horror, and pain, and chaos ; / there is no fighting her, no power can fight her, / all that avails is flight.” The Greek words Homer uses are athanaton kakon, the “undying evil”. This becomes significant when we consider the words Lycophron says of her in his Alexandra44. When she was once killed by Heracles, Lycophron says of her, “whom her father restored to life, burning her flesh with brands”. In other words, in order to restore her to life, her father burned her. Additionally, she is said alternately to be the daughter of Echidna, a mother of monsters we have already associated with Angrboda, or of Trienos, “Three Times”, a name of Ceto, the sea goddess who is the mother of sharks and sea-monsters, and sometimes even of Echidna herself. These are all relations receiving different genealogies across Indo-European spans of time, but the essentials here are her connections. They are: Scylla is an undying monster brought back to life after being thrown on the flames, drawn into connection with a “Three-Time” breeder of monsters, which include ferocious wolves or wild dogs and serpents. There is no way any serious student of Norse mythology could miss the convergence of motifs upon Gullveig-Heid, who is thrice burned but lives ever afterwards, whose evil cannot be killed, who is the mother of Fenris wolves, as well as of the great serpent, and who, as Rán, pulls poor sailors down to their deaths. Hyndlujóð says that Heid is the daughter of Hrimnir, one of the chief storm-giants in Norse mythology; while Pseudo-Hyginus in Fabulae 125 avers that Scylla's father was “Typhon”, the chief opponent of Zeus amongst the giants. He is a monstrous storm giant whom Zeus imprisoned in Tartaros. In other words, at multiple points the motifs converge. Too many to be mere conicidence. Such convergence of evidence is one of the major tests Viktor Rydberg sets for confirming identity of two different figures. To find such across the Indo-European divide is only confirmation of how deep these myths go. Those who have read Rydberg's second volume, which focuses on these deep cognates, will not be surprised, but the Indo-European identity of Ran and Scylla only adds to the catalogue Rydberg has pioneered here.

There may be further convergence in another Scylla, the daughter of King Nisos. Some have insisted this figure has been conflated with the raging sea-monster, but Ovid calls Scylla the “dogs of Nisos”, and Ovid is no mean mythologist. It is possible the story of King Nisos is a legendary figure of heroic myth, a historical figure who has passed into legend, or even a euhemerization of some kind of once-mythic figure, and that his daughter, with the same name as the monster, has been confused. However, be that as it may, it may prove of some interest that in this story, Scylla's father is said to be a rival or enemy of King Minos, a figure Rydberg has identified with Mimir, and Minos tempts Scylla to kill her father with a golden necklace. This is significant, because it would mean that the figure the Greeks called Scylla was the daughter of a great enemy of Mimir, the friend of the Gods. Moreover, that she might be enticed by a golden necklace is also of curiosity because in Saxo, we find another heiti of Gullveig, Gotvara, possessed of a golden necklace she loses to Ericus, the husband of Gunvara-Freya. Rydberg demonstrates that the artisan dwarves who created Freyja's necklace are Mimir's sons (See 'Brisingamen's Smiths'). In the story as Ovid tells it, Scylla, knowing she is the daughter of Minos' enemy, hopes to be taken hostage “as a pledge of peace” and as part of a “desired alliance”. We do not know how Heid came to Asgard from her father Hrimnir's home, but she would appear to be there as a kind of treaty-hostage or allied guest. But Minos says to Scylla, “May the Gods, O thou reproach of our age, banish thee from their universe; and may both earth and sea be denied to thee. At least, I will not allow so great a monster to come into Crete, the birth-place of Jupiter, which is my realm.” If this is Mimir, he is recommending in no uncertain terms that the Gods have nothing to do with her. Scylla, feeling scorned, flies into a rage and frenzy. Minos' ships take sail and launch. She mourns that having betrayed her people, they will never take her back, so she has no place to go. She leaps into the sea after Minos' ships, and hangs onto the ship of Minos. But her father, transformed into a sea eagle, comes to tear her into pieces. Now Ovid has her transform into a small bird and fly away. But if this story does indeed enter in to the sea monster's myth, it may well be a variant origin tale, and perhaps in the original, this is where she was transformed into the sea-monster. Being scorned by a fleeing fleet could also explain her vengeance in drowning sailors from that point on. To sum up, in Skylla we have an undying evil who cannot be killed, but who when burned, revives, from whose womb barks ferocious dogs or wolves, and who is associated with a serpent; who is herself a sea monster who kills passing sailors near a swallowing whirlpool that drags sailors down to the bottom of the ocean. On every one of these motifs we find written the signature, although in Greek and not Old Norse, of Gullveig-Heid. Thus, it would seem apparent that Skylla is the Greek cognate of Rán. |

|||||

|

FINI [Main][Home] |