|

|

|

[HOME] |

AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION TO THE

ANCESTOR TABLES

NOTES ON THE ANCESTOR TABLES

|

|

|

|

Table 1. An Ancestor Table of the Ur-beings of

Germanic Mythology |

COLOR

CODE

Red = Jotuns

Orange = Daughters

of Mimir and Urd

Yellow = Dwarves

Green = Aesir

Blue = Vanir

Purple = Elves |

KEY

(Italics) = Female

beings.

(?) = Relationships or identities that are

speculative or uncertain

(????) = Names of unknown beings

(+) Marital or extramarital sexual relationships

(↓) Non-sexual or non-biological

relationships such as foster parentage |

|

|

|

|

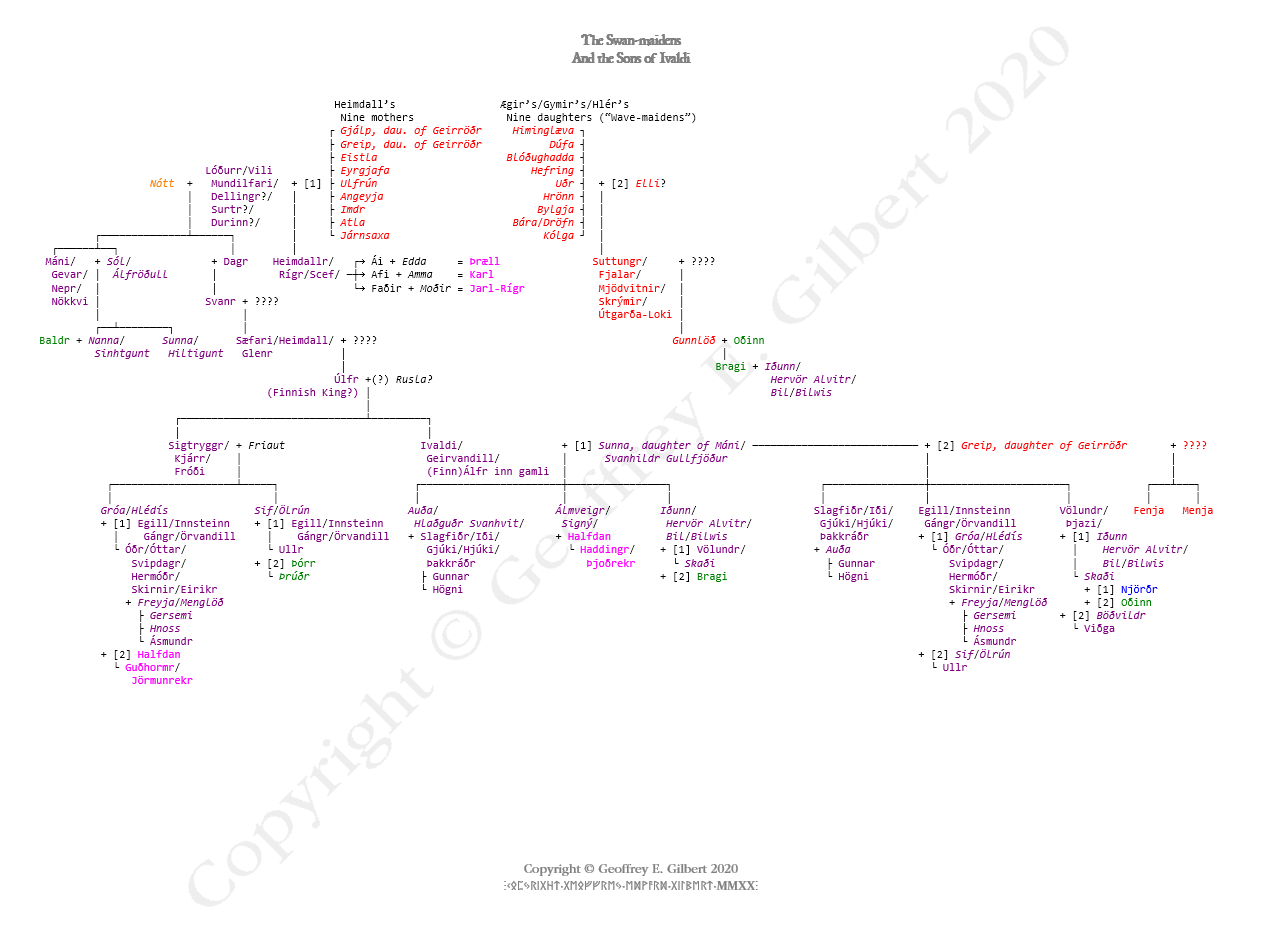

Table 2. The Swan-maidens and the Sons of Ivaldi

|

|

|

|

|

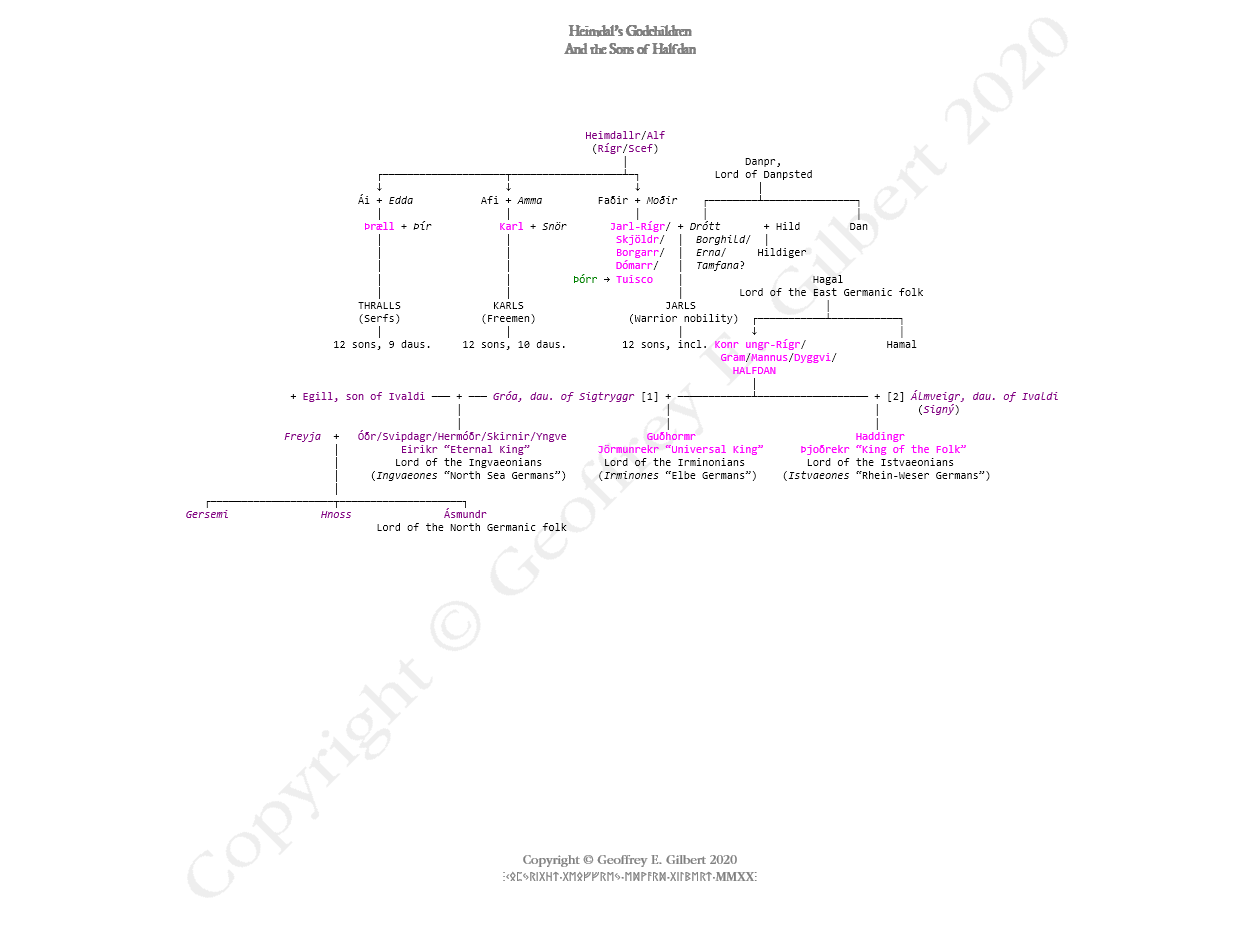

Table 3. Heimdall’s Godchildren and the Sons of

Halfdan |

|

|

|

|

AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION TO THE ANCESTOR TABLES

|

I created these Ancestor Tables (Ger.

Ahnentafeln) as part of a personal project to study

Germanic mythology more deliberately. As someone of

Germanic ancestry, I’ve always had what seems to me to

be an instinctive love for the subject going back to my

earliest memories. Now that I’m a father of my own

family, I wish to pass on my love of the myths of my

ancestors to my children. At the same time, I’ve come to

realize that my earlier understanding of the subject was

limited mostly to fairy tales, comic books, fantasy

role-playing games, and the works of J. R. R. Tolkien.

With that in mind, I’ve since taken upon myself the the

responsibility of gaining a more thorough understanding

of the subject by learning what those myths actually

are. Now that I have the time to do so, I’ve read and

continue to read as many of the sources and resources as

are available, and look for opportunities to discuss

them with others who share the same love so that I can

pass on this knowledge authentically. One particular

challenge that became obvious to me when learning about

Germanic mythology is that there is no one, single

sourcebook containing all the various Germanic myths and

legends — no Germanic “Bible”, as it were. The sources

are found in several different languages, in many

different forms (written, archaeological, or otherwise),

and are often rendered differently by those who’ve

attempted to translate them into modern English. A few

years ago, I was fortunate to have discovered William P.

Reaves’ excellent website

Germanic Mythology: Texts, Translations, Scholarship,

which is clearly a monumental labor of love. There,

Reaves has collected most if not all of the available

online sources, derivations, interpretations, analyses,

and items of tangential interest in one well-organized

location. I’ve spent countless hours reviewing this

website and learning more about the lore. At Germanic Mythology, I discovered XVIIIIth

century Swedish author Viktor Rydberg and learned that

he shared this same passion for the mythology; studied

it thoroughly not as a professional scholar, but as an

amateur poet determined to prove the independence of

Germanic mythology from the Christian; and attempted to

create one coherent epic beginning with the creation of

the Alheimur (Icel. “universe”) and extending all the

way to its destruction and rebirth at Ragnarök, the

well-known Germanic apocalypse. The final version of

Rydberg’s epic,

Our Father’s Godsaga, is now available in

English thanks to Reaves’ labors. I’d often wondered if

there was such a work: Rasmus Anderson, in Norse

Mythology: The Religion of Our Forefathers (1879), asked

if someone would take up the task of giving us “northern

art” (that is, a Germano-Norse epic) to complement the

“southern” (Greco-Roman) and the “oriental”

(Judaeo-Christian). I’ve since learned about a few other

attempts to do so, but I’m glad that Rydberg took up the

challenge... if he was even aware of it! The result is

an intriguing story that includes many elements that

were both familiar and new to me.

Rydberg was also responsible for perhaps a greater

literary achievement: Investigations into Germanic

Mythology, Volumes I and II (UGM, after the work’s

title in Swedish). Having read UGM (Vol. I was

translated into English by Anderson, and Vol. II by

Reaves), I’ve gained a profound appreciation for

Rydberg’s epic method and consider him, along with the

Brothers Grimm, to be essential reading for anyone

serious about studying authentic Germanic mythology.

Taken in conjunction with using an Eddic poetry-based

understanding of Norse Cosmology, as well as a healthy

dose of comparative Indo-European mythological studies,

I think that this is modern man’s best hope for gaining

as thorough an understanding of the subject as possible.

Another challenge to gaining a thorough understanding of

the mythology stems from the fact that the characters

found therein can have multiple names, even in the same

language, which can complicate identifying who he (or

she) is and how he relates to the other characters and

events in the stories. One of the purposes behind

creating these Tables is to help remove some of this

built-in confusion by providing a ready reference of

most if not all of the major characters and their

familial relationships. A second purpose was to help

force me to learn more about each, individual being.

Before including these characters from the mythology, I

researched each one, his relationship to the other

characters, his role and actions in the source material,

as well as his ultimate fate. By doing so, and by laying

it all out visually, I think I’ve gained a greater and

more thorough understanding and appreciation for each

character, his motivations, his biases, and (to me) some

possible insight as to why he might have taken the

decisions and actions that he did, for better or for

worse. Moreover, it has allowed me to create a more

solid foundation for extrapolating and imagining

possible motivations and actions for things that are not

found in the mythology... which brings me to my third

purpose. In accordance with my intent to pass these

stories along to my children, I’ve decided to write my

own version of Germanic mythology’s grand epic. To take

nothing away from the excellent, insightful, and

entertaining work done by others including Rydberg, just

as the process of drafting the family trees for all

these beings has helped me gain a greater understanding

for each of them, so too has it caused me to re-imagine

the course of events from beginning to end, fleshing out

the story itself. My starting point was Rydberg’s

Overview of Germanic Mythology’s Epic Order,

but I’ve gone well beyond that now. I’ve made some small progress in putting pen to

paper, but the vast majority of the work is still ahead

of me. I’ve almost certainly made mistakes in drafting

these Tables; and while I consider the majority of the

information I’ve presented accurate to the sources, I

also consider them to be works-in-progress. They’re a

“95% solution”: I don’t know if anyone can ever render

the various identities and genealogical relationships of

these mythological beings with 100% accuracy, but I

think I’ve come pretty close. As an aspiring author,

I’ve also taken a bit of artistic license in attributing

spouses to certain beings that either don’t have them

otherwise, or where the sources are ambiguous, unclear,

or silent on the matter. I’ve indicated in the notes

below where I’ve done so and why. At face value, taking

this approach might seem to contradict my purpose of

passing on the tradition of Germanic Mythology

accurately: I leave it to the reader as to whether or

not this has compromised the overall effort. |

Geoffrey E. Gilbert

Winterfilleth 2020

|

[BACK

TO TOP][HOME]

|

|

NOTES ON THE

ANCESTOR TABLES

|

1 — The color code is: red for the Giants

(Jotuns and Thurses), orange for the daughters of Mimir

and Urd, yellow for the Dwarves, green for the Aesir,

blue for the Vanir, and purple for the Elves. This

“rainbow” ordering of colors mirrors, roughly, the order

in which each class of beings was created or came into

being. For simplicity, in the case of “mixed marriages”

the offspring take the father’s color unless otherwise

noted. Names in italics indicate females. Relationships

about which I’ve speculated or of which I’m unsure are

indicated by a single question mark (?). Names of

unknown beings are indicated by four question marks

(????). I’ve opted to use a plus sign (+) rather than an

equals sign (=) to indicate marital or extramarital

sexual relationships. Arrows (↓) indicate non-sexual or

non-biological relationships such as foster parentage,

as in the case of Vingnir, Hlora, and Thor; or

godparentage, as in the case of Heimdall.

2 — The names included in the Tables themselves, are

with few exceptions, in Old Norse or modern Icelandic.

I’ve tried to include the names of most of the more

prominent, well known, and otherwise relevant beings. In

many cases, I’ve given more than one name for the same

being to help in cross-referencing certain

relationships, though obviously I could not include them

all. Those names are presented in English

transliterations or other versions I prefer in these

notes. Some such versions might not be intuitively

obvious to those already familiar with the subject. For

example, for stylistic reasons I like to use the Old

High German name “Frija” for the name of Odin’s wife,

and the more English “Dwalin” for Mimir’s son Dvalin.

Where possible, I’ve tried to place each generation of

beings on the same horizontal level in order to give

further context to their relationship with each other.

For example, I put Bolthorn on the same level as

Aurgelmir in order to imply their identity with one

another. I put Fornjot at the same level, too, though

I’m not currently of the opinion that Fornjot is

Aurgelmir. The ordering from left to right of siblings

is meant to imply birth order, eldest to youngest. Thus,

Thrudgelmir on the left is shown to be the eldest of

Aurgelmir’s offspring, with Mimir and Urd being a

younger set of twins. Likewise, the common naming of

Odin, Vili, and Ve, or Odin, Hoenir, and Lodur is

instead set forth as Lodur, Hoenir, and Odin, with Lodur

as the eldest and Odin as the youngest son of Bor. This

has relevance in my own imagination and interpretation

of the theme of birth order and the role that

primogeniture and ultimogeniture appear to have in

causing enmity among siblings, particularly brothers.

3 — Also, I’ve used the theory “Lodur = Surt”. This

theory was introduced to me by William Reaves, who got

it from his friend and fellow-mythologist Carla O’Harris.

4 — Granted, not every aspect of the mythology needs a

rational explanation. Nonetheless, to aid in giving the

epic a greater sense of realism (as mentioned above),

I’ve provided certain beings with spouses who, as far as

I know, have never before received them. In the eldest

days, the possible candidates are quite limited, so some

improvisation was necessary. Perhaps the most unorthodox

suggestion I’ve made is to imply that Aurgelmir and

Audhumbla together are the natural parents of

Thrudgelmir, Mimir, and Urd. Thus, I’ve imagined

Audhumbla to be an actual female man-like (“humanoid”)

being whose milk gives Aurgelmir the potency to generate

their offspring. “Audhumbla + Buri” is likewise an

improvisation to identify Buri’s wife and Bor’s mother.

Interpreting Audhumbla’s character in this manner seemed

fitting to me, among other reason but for the simple

fact that she is the only female being that we know of

who was present at the beginning of time; both Aurgelmir

and Buri are male beings who have children; and males by

definition do not bear children. I also think that the

idea of Audhumbla as one female desired by two males

sets up a natural tension borne of sexual jealousy among

this trio — not in a Romantic, Victorian “love triangle” sense, but from the standpoint of sheer

survival in an ancient, savage world. If left otherwise

unresolved, this tension could (and in my imagination

did) erupt in murderous violence. Moreover, in Vedic

tradition there is a motif of an evil king slaying the

first cow (Sw. Urkon) being considered the primary

offense. Likewise, I imagine the death of Audhumbla to

be the key event which causes the division of the gods

and the giants into mutually-opposed, hostile camps,

setting into motion the entire chain of events which

leads ultimately to the Götterdämmerung at the end of

time. It seems probable to me that Buri and probably Bor

were the primary objects of that violence during the

events leading to Audhumbla’s death. Thus, the slaying

of Ymir (Aurgelmir’s name among the gods) by Odin and

his brothers becomes justified: they were in fact

seeking vengeance for the murders of their father,

grandfather, and grandmother; and then the Sons of Bor

use the body of their defeated enemy to create the

world.

5 — Following this logic, Thrudgelmir likewise needed a

wife. I’ve suggested Urd, whom I think would most likely

have been espoused against her will. Bergelmir, as

Hrimnir, has a wife named Hyrja though her origin is not

explained. Therefore, I’ve identified her as one of

Mimir and Urd’s 12 daughters (see note 7, below, re:

Verdandi), whose espousal likewise might have occurred

against her will. The theme of taking brides without

their consent occurs elsewhere in the epic, so I think

it wouldn’t be unheard of at this point. For the purist,

these interpretations can be easily disregarded in the

Tables. Audhumbla may simply remain the primeval cosmic

cow, while Aurgelmir, Thrudgelmir, and Buri can somehow

remain fecund bachelors.

6 — I’m currently unsure of how to classify Buri and

Borr, so I’ve kept them in black (normal) text for now.

7 — My interpretation of the “Greater Norns” — the Fates

of Germanic mythology — is based on the “crone, mother,

maiden” motif which seems to fit the “past, present,

future” implied aspect of the Urd, Verdandi, Skuld trio

even if it isn’t explicitly defined that way in the

mythology. Urd is an ancient, powerful being, one of the

eldest in the mythology, so a “past”/“crone” aspect

seems easily justifiable. The Valkyries as unmarried

women/maidens also seems to leave room for Skuld (who is

also a Valkyrie) in the “maiden”/“future” role. The

“missing link” is Verdandi: who might she be? Mimir and

Urd together had 12 daughters, only two of whom are

named: Nott and Bodvild. It seems possible to me that

Verdandi could be one of the remaining ten. But who is

Skuld’s father? Skuld is the foremost Valkyrie listed in

Voluspa 30. This, taken together with her role as a

Norn, could imply that Skuld held some sort of primacy

amongst the Valkyries. If so, then who would be a likely

candidate to father the such a prominent Valkyrie? I’ve

omitted the Dwarves and the Giants as possible fathers,

which leaves the Sons of Bor. It’s perhaps significant

to point out that Mimir and Urd’s eldest daughter Nott

is already known for having been espoused to both Lodur

and Hoenir and becomes the ancestress of both the Elves

and the Vanir, respectively. Odin, the youngest son of

Borr, either could have taken or could have been

assigned Verdandi as his mate even if only for the

purpose of fathering Skuld, the third Norn but first of

the Valkyries. Again, there is no proof of this theory,

and the reader is welcome to dismiss it at his

discretion.

8 — Also, there are “Lesser Norns” who are drawn from

the Aesir, the Elves, and the Dwarves. As the Dwarven

Norns are drawn from “Dwalin’s daughters”, this also

implies that the Dwarves can take wives and that there

must be female Dwarves. (Whether or not they have

beards, I’ve not yet established!) Thus, I’ve included

Dwalin’s daughters, though none are named.

9 — I’ve assumed a total of seven and possibly nine

Dwarves created by Mimir without the aid of a wife or

lover. That there are seven Dwarven sons of Mimir is

implied by the medieval myth of the Seven Sleepers. The

possibility of nine sons of Mimir arises from the fact

that two unnamed sons were slain by Volund during the

latter’s captivity later in the epic, though there are

yet Seven Sleepers who will awaken at Ragnarok.

Moreover, multiples of three (3, 6, 9, 12) tend to be

more prevalent in Germanic Mythology; so it would be

fitting if there were nine Dwarves, at least originally,

rather than seven. It is equally possible that those two

sons were the natural sons of Mimir and Urd. For now,

however, I’ve included them in the Dvergar, under Mimir

alone.

10 — The genealogy of the Elves is perhaps the most

difficult to establish. Using Rydberg’s theory that the

Elves originate with Lodur (as Mundilfari) via Heimdall,

Heimdall’s identity and relationships become important

to establish. Heimdall had nine mothers. Somehow, Lodur

begat Heimdall upon those nine beings collectively: how

he did so is a “mystery of the faith”. Lodur (as Delling

“Dawn”) together with Nott (“Night”) created Dag

(“Day”). From Reaves’ website, Eysteinn Björnsson

suggested that Heimdall is actually Dag. However, it

seems impossible for Heimdall to be both the son of nine

mothers and of one, especially when the one is not named

as one of the nine. To resolve this discrepancy, I’ve

imagined that Heimdall was “born twice”, at two

different times: by the same father, but by different

mothers. Following Rydberg, we know that Heimdall was

born of the holy friction fire created by Lodur

(Mundilfori) with Heimdall’s nine mothers. After a time,

Heimdall (as Scef) was sent to Midgard in a boat as a

child to bring that same fire, as well as culture,

social hierarchy, and organization to the early Germanic

people. After his mission to Midgard was completed, he

died, and his body was set in the same boat in which he

arrived and pushed out to sea. And yet, that is not the

end of Heimdall’s story. He is alive later in the epic

as guardian of the Bifrost, and will confront Loki at

the final battle during Ragnarok. Thus, somehow Heimdall

must have returned to life after dying in Midgard. I

imagine it’s possible that Lodur (Delling) and Nott

“recreated” Heimdall in his second incarnation as the

“Day”, allowing him to reclaim Sol as his wife (perhaps

after some adventure) and earning the epithet “Glen”

(“the Gleaming One”) for literally having brought light

and enlightenment to Mankind. This of course begs the

question how this is possible and under what

circumstances; for now, I’ve left the matter unresolved.

Heimdall is, afterall, something of an enigma.

11 — As an aside, while Lodur is considered to be the

forefather of the Elves, and Lodur is also Heimdall’s

father, Heimdall is considered to be one of the Vanir:

not the Elves. Hoenir is the forefather of the Vanir.

Consequently, I’ve “corrected” this discrepancy by

putting Heimdall’s name in purple text — that is, as one

of the Elves. I listed Aegir’s nine daughters alongside

Heimdall’s nine mothers, though there’s no known direct

correlation between any of them. Two of Heimdall’s

mothers — Gjalp and Greip — are the daughters of a being

named “Geirrod” (not Aegir), so it’s unclear to me if

all of the daughters are siblings. Greip is also the

mother of the Sons of Ivaldi. Thor slew both Gjalp and

Greip during his adventure to Geirrod’s homestead. This

would, to me, be a factor contributing to the enmity

between the Aesir and the Elves, though Heimdall himself

is not recorded as having become hostile to Thor.

Jarnsaxa (another of Heimdall’s nine mothers) becomes

Thor’s lover, and by him the mother of Magni. The

identity of Modi’s (Thor’s son’s) mother is not stated

in any of the sources: I’ve simply assumed that Magni

and Modi are twins solely upon the basis that their

names alliterate; and therefore, Jarnsaxa is Modi’s

mother as well.

12 — Concerning Aegir (a Sea-jotun), he is apparently

the son of a being named Fornjot, and he has brothers

Logi (a Fire-jotun) and Kari (an Air- or Wind-jotun).

I’ve seen Fornjot identified as possibly Aurgelmir/Ymir,

but that would have to mean that Aurgelmir had more

children than Thrudgelmir, Mimir, and Urd; and there’s

no evidence to suggest that, that is the case. Perhaps

Fornjot is either Mimir or Thrudgelmir. I think it’s

unlikely that Fornjot = Mimir. I’m not sure about

Fornjot = Thrudgelmir, but I don’t think so at this

time. Thus, for now, Fornjot is noted as being distinct

from Aurgelmir and Thrudgelmir, though this does leave

open the question of his ancestry. Interestingly, Logi

also appears among Suttung/Skrymir/Utgard-Loki’s retinue

in the Mythology.

13 — Concerning Suttung (Surt ungr or “Surt the

Younger”), as the son of Surt/Lodur he must have a

mother, but none is given. I’ve used Elli, the old Jotun

who wrestles with Thor, as Suttung’s mother even though

she does not seem to command the respect that a mother

would be expected to have at Suttung’s court. Also, I

have no answer as of yet as to Elli’s origin. However,

she wrestles successfully against Thor, so she must be a

being of immense power, of a greater order than Thor.

This implies to me very ancient giant, possibly

Fornjot’s unnamed wife. (Fornjot is, literally, “ancient

giant”, and Elli means “old age”.) To a certain extent,

that might also explain why Logi appears in the company

of Suttung: they could be half-brothers through their

mother.

14 — The names of the nine valkyries listed as Odin’s

daughters by Frija are taken from Wagner’s Der Ring des

Nibelungen (RN) and I’ve translated them into Old Norse.

I know RN is derivative and is not considered canonical.

In RN, Odin begets the Valkyries on Erda, instead; and

Erda (OHG “earth”) = Jord (ON “earth”), so it didn’t

seem completely unbelievable to me that Odin could have

fathered Valkyries with his actual wife. Again, this is

artistic license on my part. I do like the idea of nine

“riders”; again, nine being an important and perhaps

holy number to the ancient Germanic peoples. Also, the

Jotun Aegir has nine daughters as well, so it wouldn’t

be unprecedented for another being of similar stature to

have nine daughters. In any case, if the reader thinks

this idea problematic, he can substitute names of other

Valkyries of his choosing, or ignore the idea

altogether.

15 — Using the proposed genealogy of the Elves at

Reaves’ website (http://www.germanicmythology.com/original/GeneologyoftheElves.html),

I’ve made Sigtryg and Ivaldi the sons of Ulf.

Furthermore, Rydberg stated that Ivaldi’s mother was

Rusla “the Red Maiden”, the mortal daughter of King Rieg

of Telemark. I’ve included her name in the Tables as a

placeholder: I’m not sure that the timing will make

sense with her identified thusly, although the name

could be based on some other mythological character.

16 — I’ve named Loki’s daughter “Leikin-Hel”, in a

manner similar to how Suttung is also named

“Utgard-Loki”. It was Rydberg who identified Loki’s

daughter not as Hel (“Hel” is another name for Urd), but

as “Leikin”. As she has no other name, one could easily

drop the suffix and simply refer to her as “Leikin”,

though this is currently an unfamiliar name for this

particular being. My use of “Leikin-Hel” will hopefully

help the reader maintain the link between Loki’s dauther

and her role as the queen of Niflhel (where damned souls

go for torment in the Germanic afterlife). The being Hel

(that is, Urd) is distinct from Leikin-Hel: Hel is

Mimir’s wife and thus queen of Jormungrund (the

Underworld); she is the mother of Natt, Bodvild, and

their sisters; she’s the mother of the sons of Bor; and

she’s the foremost of the Norns. “Hel” is also another

name for the Underworld.

17 — Also, with regard to Loki’s and Gullveig’s

genealogy... Gullveig, as Heid, is the daughter of

Hrimnir; and I’ve seen Hrimnir identified as Bergelmir.

Hrimnir’s wife is identified as Hyrja (whom I’ve

suggested is a daughter of Mimir and Urd). Loki is the

son of Farbauti and Laufey/Nal. It’s possible that Loki

= Hrossthjof, and that would mean Hrimnir = Farbauti:

possible, and if so, either Laufey/Nal is another name

for Hyrja or she is another female being altogether.

(Perhaps another of Mimir’s unnamed daughters?) I think

that if Farbauti = Hrimnir, then it’s more likely that

Laufey/Nal and Hyrja are two distinct female beings,

since Loki is also supposed to have two brothers

(Byleist and Helblindi) who are not listed as sons of

either Hrimnir or Bergelmir. Either way, that would make

Loki and Gullveig either full siblings or half-siblings.

Of course, Loki and Gullveig could not be siblings at

all. Loki and Gullveig’s children — Fenrir, Jormungand,

and Leikin-Hel — are listed. As Gullveig is identified

as Ran (the wife of Aegir), Loki and Gullveig’s

monstrous children are half-siblings to Aegir’s nine

daughters, the nine Wave-maidens.

18 — Of minor note,

Rind (whom Odin bewitches and rapes in order to father

Vali) is the daughter of Billing; and Billing can be

identified with Hoenir, Odin’s brother. If true, this

would make Rind not a Jotun, but one of the Vanir,

possibly another daughter of Hoenir and Natt.

19 — With regard to Eir, I’ve listed her as a sister to

Njord and Frija, though this is nowhere stated in the

lore. She could simply be part of Frija’s entourage.

20 — Also, I’ve indicated Grid the mother of Vidar (by

Odin) as possibly the (bastard?) daughter of Geirrod. As

such or perhaps because of her relationship with Odin,

she could have been excluded from her kinsmen; and that

could explain why she was willing to give Thor aid and

comfort during his adventure to Geirrod’s homestead.

21 — Regarding the matter of Tyr’s unnamed wife, I’ve

included her as Sigyn, known to be Loki’s wife from

Lokasenna. This is a theory advanced by William Reaves.

22 — Concerning Heimdall’s godchildren, I use the term

"godchildren" to describe the relationship between

Heimdall, Thrall, Karl, and Jarl. It could be that he

was their natural father, or it could be that he just

hallowed their parents marriage by virtue of visiting

them and accepting their hospitality. Rigsthula suggests

fairly strongly the possibility of Heimdall (interpreted

as Rig) having fathered Thrall, Karl, and Jarl by

sleeping between their parents, while their mothers

nonetheless became pregnant; yet it does not state this

explicitly. To me, any tale of serial, divine cuckoldry

would bring dishonor upon the fathers and could not be

portrayed in a positive light. Consequently, I interpret

the events of Rigsthula as Heimdall visiting Ai’s,

Afi’s, and Fadhir’s households, spending time with them

as an honored guest, blessing each marital union, and

thereby sanctioning the three traditional classes of

ancient Germanic society. Again, the chart can be read

and interpreted either way.

23 — With regard to the Sons of Halfdan, it’s important

to remember that there are two, not three, natural sons:

Gudhorm (by Groa) and Hadding (by Almveig). Swipdag/Od

is Groa’s son by Egil whom Halfdan slew before taking

Groa captive and later impregnating her with Gudhorm.

It’s highly doubtful that Swipdag considered himself

Halfdan’s son in any meaningful way. Moreover, the fact

of Egil’s slaying and Groa’s captivity and impregnation

is what sets up the conflict among Swipdag and Halfdan’s

sons.

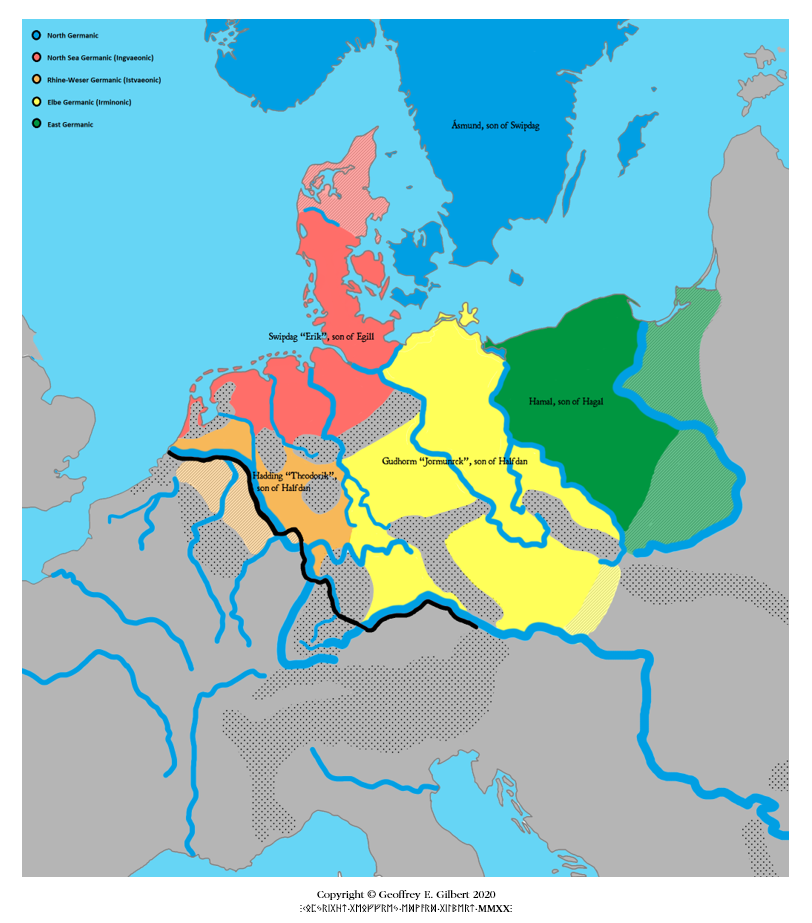

24 — Another item of possible interest is the alignment

of Swipdag, Gudhorm, and Hadding as lords (jarls?) of

the Ingvaeonians, Irminonians, and Istvaeonians with the

three branches of the Northwestern Germanic languages:

North Sea Germanic (“Ingvaeonic”), Elbe Germanic

(“Irminonic”), and Rhine-Weser Germanic (“Istvaeonic”).

I’ve provided a map (“Epic Heroes and Germanic

Dialects”) to supplement these Tables that demonstrates

how and where these lords and languages would be found,

roughly. The map includes the Eastern Germanic

(“Gothic”?) people under Hamal son of Hagal (who

fostered Halfdan at Skjold’s request and was present

during Halfdan’s kidnapping of Groa, and later provided

refuge to Hadding during the war between Swipdag and

Halfdan’s sons) as well as the Northern Germanic

(“Norse”?) people under the kingship of Asmund son of

Swipdag.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|