| |

|

|

|

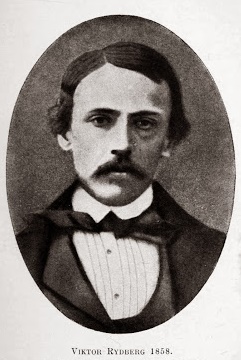

In recent decades, it is often stated that Viktor Rydberg was a

homosexual with an erotic interest in young boys. No direct evidence,

however, supports this sensational

claim. At its heart, the argument is literary, based on

selective readings of Rydberg's published works and personal

letters, interpreted through a modern lens. The core source material

consists of seven

handwritten copies of personal letters which Rydberg wrote to

his former student Rudolf Ström (born 1842) between 1856–1862, now found in the

collection of the Royal Library in Stockholm. The transcripts,

made by Rydberg's wife Susen, include, among other things,

expressions of affection toward the teenage Rudolf Ström. That

they are copies of the originals has aroused suspicions that

they were edited by Mrs. Rydberg, or worse censored. One of the

reasons for the speculation is that the envelope in which the

letters are filed states:

|

|

"The originals of these letters

have been searched for many times by the staff of the Royal

Library at the request of the librarian S. Hallberg in

Gothenburg. They were probably intentionally destroyed

by the Ström family."

|

|

|

|

|

The theory that Viktor Rydberg was homosexual with an interest

in young boys originated with Victor Svanberg, a self-professed

gay literary critic who based his claim solely on passages from

Rydberg's published works and personal letters, none of which

actually attest to Rydberg being gay. No new sources have been

cited since 1928 when Victor Svanberg, then an associate

professor at Uppsala University, first made the argument,

more than three decades after Rydberg's death in 1895. Thus,

these copies of Rydberg's letters are the sole source

behind the claim. The most compelling argument for Rydberg's

alleged same-sex orientation remains Svanberg's premise

assuming purposeful omissions in the letters and the willful

destruction of the originals. When Svanberg presented the

hand-copied letters as evidence in his book Novantiken i Den

siste atenaren ["Greek Antiquity in The Last Athenian"], he

emphasized their supposed censorship, noting: "The letters

were only been accessible to me in copies," adding that "In the

copying, certain omissions have been made and indicated.” Thus,

the argument is one of omission and innuendo. It isn't what the

letters say, but what has allegedly been left out that is

necessary to draw this conclusion.

With his seemingly secure statements about censorship of the

copies, Svanberg succeeded in raising suspicions that there was

something sensitive in the original letters which the Rydberg

and Ström families wished to conceal. Over seventy years later,

Greger Eman, writing for the gay publication Lambda Nordica, returned to the allegedly censored letters at the

Royal Library. Without evidence to substaniate his claim, Eman

states that large parts of the collection were burned. The

letters that remain are, he continues, "censored copies

from

Susan's hand". Eman's confident conviction that the originals were burnt

and that the copies are censored is crucial to his conclusion

that both Rydberg's and Ström's relatives tried to conceal that

Rydberg had a homosexual orientation.

|

Eman, Greger.

Gossen Snövit: Passioner och

förpliktelser hos Viktor Rydberg. Lambda

Nordica, 5:2-3, (1999), pp. 6-41. [This is a pdf download]

|

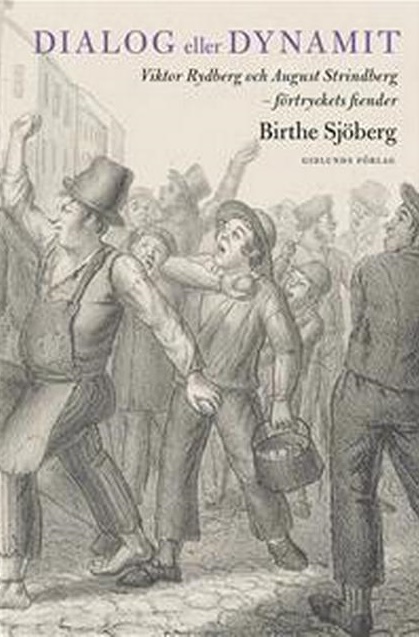

THE DISCOVERY of NEW EVIDENCE

|

The original letters have since been found in the Norwegian

Library of Letter Collections in Linköping. As detailed in

her 2018 book Dialog eller dynamit: Viktor Rydberg och

August Strindberg-förtryckets fiender, Professor Emeritus

Birthe Sjöberg of the University of Lund, following a tip from city archivist Åke

Carlsson, succeeded in locating all originals to the copied

letters in May 2017. The originals were not "deliberately

destroyed". Instead, they have been preserved with care,

as Rudolf Ström attests in a letter to Rydberg, dated October 26,

1892, how his "warm children's soul was attached" to Rydberg,

"the first real friend I acquired". He continues:

"Your subsequent affectionate letters to me bear the most

beautiful testimony thereof, letters which are now preserved

with envious tenderness by my dear, little wife." [Dina

sednare, kärleksfulla bref till mig bära därom det skönaste

vittnesbörd, bref, som numera med afundsjuk ömhet bevaras af min

kära, lilla hustru. ]

|

|

Rudolf Ström (born 1842) died in 1913, and in 1937, Abela Hallin, the aunt

of Rudolf Ström's wife Abela Wallenberg, donated the

well-preserved letters to Stiftsbiblioteket in Linköping.

The envelopes are postmarked "Gothenburg" plus the date, but the

stamps have been cut off. There are remnants of sealing wax on

the back. They are addressed to "The student Mr. Rudolf

Ström, Linköping, Bleckenstad". For a time, Rydberg added the

name Gustaf and wrote: "The student Mr. Gustaf Rudolf Ström,

Linköping, Bleckenstad". When Rudolf moved to Stockholm, the

letters were addressed to "Student at the Institute of

Technology, Mr. Rudolf Ström, Stockholm".

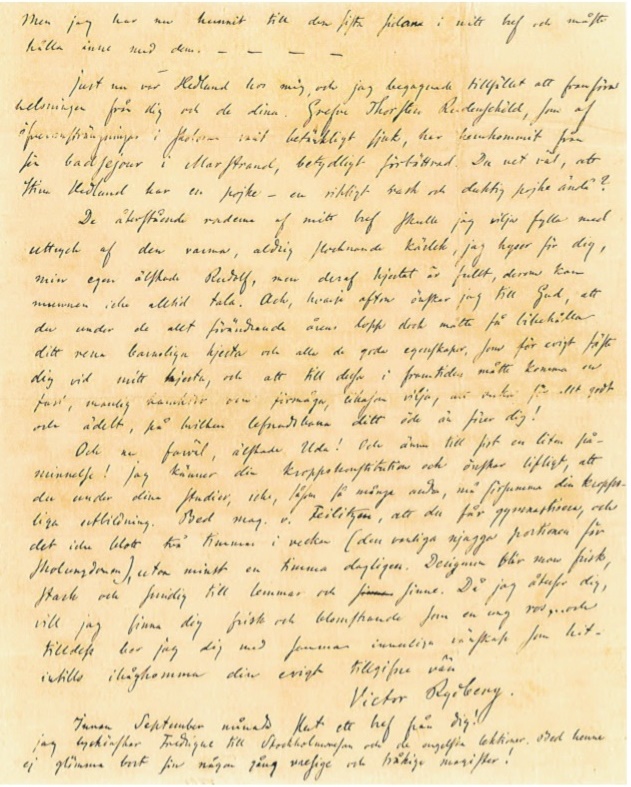

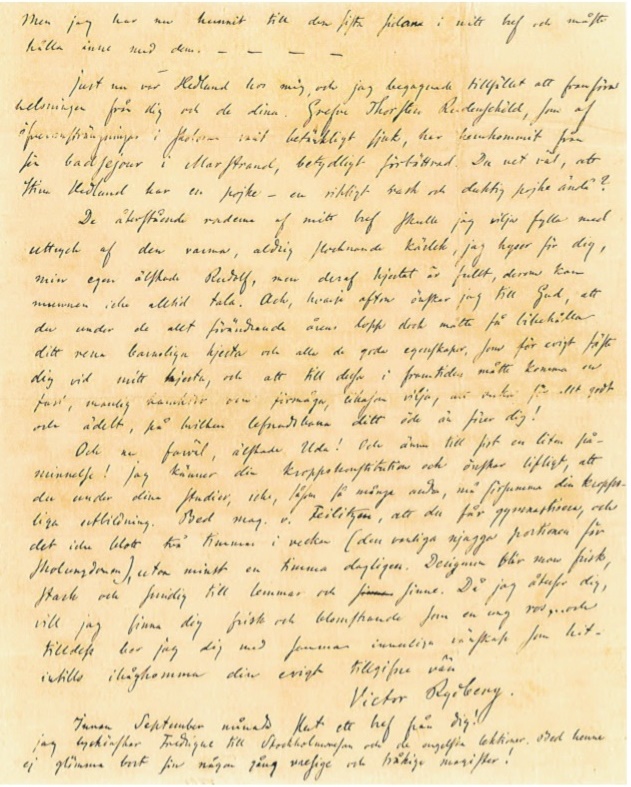

Having compared the originals with the transcripts found in the

Royal Library, Professor Sjöberg found every word

reproduced correctly. Thus, when he writes that "certain omissions

have been made and indicated" in the transcriptions, Svanberg is

incorrect. Some of the markings he refers to are also found in

the original, for example, in the oldest letter, Rydberg marked

one pause with four dashes in a row (see picture); other marks

are not found in the originals or in the transcriptions. Thus

claims about censorship of the letters in the Royal Library are

baseless. Susen Rydberg did not omit anything in the letters

she copied.

Source: Sjöberg, Birthe. Dialog

eller Dynamit? (2018), pp. 29-35.

|

Rydberg's Letter to Rudolf Ström,

dated September 2nd, 1856 as published in

Birthe Sjöberg's Dialog eller

Dynamit: Viktor Rydberg och August Strindberg

(2018).

|

|

Similar speculations have been made

about Rydberg's marriage to Susen Hasselblad. According to

Professor Sjöberg, the only 'safe' source on this subject is a

conversation that literature historian Olle Holmberg had with an

anonymous friend (dubbed "Mrs. L.") of Susen Rydberg in 1933,

over fifty years after the couple married. Interviewed just five

years after Svanberg published his theory about Rydberg's

supposed gossekärleken ('love for boys') which shocked

their contemporaries, "Mrs. L" story may have been influenced by

it. According to Holmberg, she said: “Viktor Rydberg lived

in asceticism for the first part of their marriage. His wife did

not understand this, and thought that it was somehow related to

his poetry. When he later wished to approach her, she was tired

of waiting and did not want to." Holmberg conducted the

interview when he was writing Viktor Rydberg's Lyric (1935), but

chose not to include it in the book. It was not until 1948 that

he included the interview together with other remaining material

in a Swedish literary journal. As for the veracity of the tale,

Holmberg's own words must be quoted:

"The obvious reservation

that should accompany all stories of this kind, that human

memory is fragile and that oral tradition has never been 100

percent reliable, need not be emphasized.”

The same interview got a bigger

audience twenty-five years later when Hans O. Granlid included it

in his oft-quoted anthology Vår Dröm är Frihet

[Our Dream is Freedom, 1973]. But Granlid too added a warning: "It should be read with

a criticial eye." As Professor Sjöberg observes, Holmberg and

Granlid likely would have been more critical of Mrs. L's story

if they had known Svanberg's theory lacked foundation. But

neither Svanberg, Holmberg nor Granlid knew of the existence of

the original letters. Nor were these three researchers unique in

that respect. Not one of Professor Sjöberg's forerunners in

Rydberg research knew about the original letters, and this is

probably why Svanberg's conclusions have been accepted by an

ever growing group of researchers. From their statements, it is apparent that the alleged 'love for

boys', as well as the alleged censorship and destruction of the

original letters underlies the speculation about Rydberg's

marriage.

Source: Sjöberg, Birthe. Dialog

eller Dynamit? (2018), pp. 29-35.

|

Viktor Rydberg (center) with the

Hasselblad Family

at their summer home in Bångsbo, Släp parish, near Särö.

|

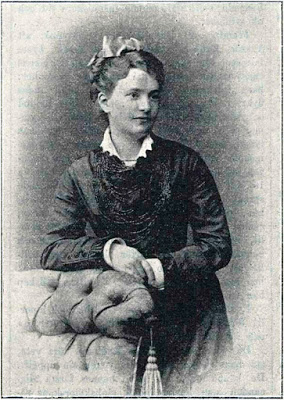

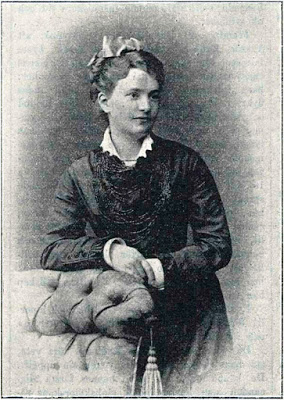

In a tribute to "Susen

Emilia Rydberg" (born 1849) published in the journal

Idun on October 4th, 1895 shortly after her husband's death,

author Nils Linder recounts a personal story about Viktor

Rydberg:

|

"So strong was Rydberg's love for his mother - which

he already lost when not yet fully six years old - so deeply

devoted was he to the memory of her, that on many occasions,

especially at the tender moments of his life he seemed to

see her in living form. From a scientific point of view,

such visions are nothing surprising or inexplicable.

Credible stories about such things are abundant, and Rydberg

was just one of the many great and reputable personalities,

who believed they received revelations in this way.

From 1876 to '78, Rydberg gave public lectures in

Gothenburg. For these he always prepared with utmost care,

i.e. through writing down every word he would say and

through carefully reading his concept. Thus, the audience

did not have to fear any involuntary omissions by the

lecturer or any stuttering attempt to recover a lost thread

in the presentation. But once - probably in the Spring of

1878 - the audience of these lectures was surprised to see

the man in the chair come undone for a few moments. The

cause of this incident was never known to the larger public,

but individual friends heard Rydberg's own explanation of

what had happened:

Once, when he looked out into the lecture hall, he saw a

vision that made him forget everything else in the world:

before his eyes he saw his mother, alive. She stood beside a

young woman present in the hall, whom Rydberg had met a few

times with the family where he spent most of his time in

Gothenburg and was treated as a member. If my memory does

not fail, Rydberg, when he talked to me about this vision,

added that the figure had, by some special means,

brought attention to the young woman, who not long

afterwards became his betrothed and later his wife.

In my collection of Rydbergiana I have found a newspaper

clipping dated the 16th of May 1878. Under the rubric

"Viktor Rydberg on Visions" it is said that a couple of

weeks prior, he had halted during a series of public

lectures he held in Gothenburg - which discuss, among other

things, sensory phenomena — with an explanation of

'visions', most often manifested in the visual field of the

mind, but which also can effect other senses— that

they are due to 'a process within the soul itself, in which

a memory emerges or an image is reproduced with such

extraordinary strength that it acts on the senses in the

same way a real object would.'"

|

Abraham Viktor Rydberg,

1876

48 years old

|

Susen Emilia Hasselblad, 1878

29 years old

|

|

One day at the end of August 1878 Susen Emilia Hasselblad and

Viktor Rydberg, already then widely celebrated as an author,

plighted their troth to one another at Bångsbo, not far from

Särö, in Halland. A few weeks later the engagement was

announced, in the customary manner, for kinsmen and friends. The

wedding was celebrated on March 14, 1879 in Gothenburg, at the

home of the bride's parents. This day commenced a period of

marital bliss for both spouses. The union was made in mutual

love, high regard and trust. But nevertheless, Viktor Rydberg's

wife had a difficult and responsible role to fill. At that

time Rydberg celebrated his wedding, his health was far

from satisfactory. Among her first duties as wife, Susen

considered the role of nurse to be the highest. Immersed in his

research and writing, the noble scientist and poet was generally

uninterested in external affairs. His wife took care of

the cardinal issues of life, remaining constantly and

incessantly vigilant in her duties. She kept his promises and

connections, remembering them and making sure they were

completed. That she had a heart for service to others is

clear. In her own words to an admired friend, Julia von Vollmar,

dated October 24, 1887, Susen says:

"If I were not where I am — if Viktor did not need me, no

matter how insignificant I am, I would, of all things in the

world, want to be your maidservant."

*

Rydberg often spoke with pride and heartfelt

satisfaction about his excellent "secretary" and "librarian".

For more than 16 years, Susen contributed, infinitely more than

anyone else, to the artist's learning and thought-life, by

preparing a home and a home life, which met all his needs and

desires, and which he therefore became increasingly reluctant to

leave, when it came to visits with relatives and friends.

To this period belong the vast majority of Rydberg's poems, his

Investigations into Germanic Mythology (1884-1889)

and Our Fathers' Godsaga, his last novel

Vapensmeden (The Gunsmith) and Varia. Almost

the entire time, Rydberg also conducted college lectures, which

claimed a large part of his time. His wife's role was critical

to his work; even those who stood outside their circle of family

and friends could draw this conclusion from the volume and

nature of his writings.

In the same issue of Idun mentioned above, Eva Fryzell,

a member of the Svenska Literatursällskapet,

memorialised the poet in this manner:

|

"Viktor Rydberg received as his lot,

priceless happiness born in noble women's hands. With

reverence and love, he spoke of the early passing of his

mother, and during life's most important moments he thought

he could see her guiding hand. He had many female

friends; and she who stood closest to his heart, his devoted

wife, herself co-joined a spouse's and a mother's tenderness.

Female love was devoted to him in rich measure. No Swedish

skald ought to live as long as he in the grateful memory of

Swedish

women. "

|

*Source: Lund, Tore. "Brev från

Susen (nyupptäckta brev från Susen Rydberg till väninnan Julia

von Vollmar)",

Veritas, 26, Dec. 2010. Julia's

father was the wealthy wholesaler Victor Abraham Kjellberg

(1814-1875), brother of Susen's mother Susanna. Two of Julia's

siblings married siblings of Susen.

|

Viktor and Susen Rydberg

|

By all accounts, Rydberg

was a private person who never spoke of his personal affairs.

His personal letters therefore remain the best window in his

soul. He was a deeply spiritual man whose novels and poems have

often been described as ideally philosophical in nature, and

less kindly as "sexless". If he had homosexual tendencies, there

is no direct evidence of it, and none that he ever acted on them

with anyone, much less with his young pupil Rudolf Ström! Even

Svanberg doesn't make that ugly accusation. Those who make this

claim have strayed far from the source material. As Rydberg's

recent biographer, Judith Moffett (2001), writes:

|

|

"We can construct a story of backdoor

illicit liasons and front door respectability from these

fragments and others— Rydberg would hardly be the first, if it

were true— but he never spoke openly about his personal life at

any time, and so our best guess would still be guesswork."

|

|

Viktor Rydberg's most comprehensive biographer, Karl

Warburg, author of Viktor Rydberg: A

Biography (1900), wrote of Rydberg's

marriage:

"In his personal and public life and position,

an important change occurred towards the end of the

1870s: his engagement and marriage. The idea of

forming a home of his own had been a good dream as a

bright future for him in his youth; but conditions had

not allowed him to realize it. Now that he was at the

height of maturity and approaching the half-century

mark, it came to pass when he was engaged in October of

1878 and married on March 14, 1879 to Susen Emilia

Hasselblad, daughter of the wholesaler Fritz V.

Hasselblad and his wife, Susen Kjellberg, in Gothenburg.

Viktor Rydberg's wife had an eye for the importance of

providing him with peace to work, and did what she could

to remove disruptions and obstacles. She took on the

burdens of the practical duties, adapting the poet

and thinker to domestic life as much as possible. His

female companion during these years was certainly an

essential part of the harmonious mood which so favorably

marked Rydberg's last days, and in these

conditions, Rydberg produced rich work during his last

fifteen years— in calm and quiet. With all fervor he

called her 'his very best friend on earth' and 'his

other self in all things good'. With feminine sacrifice,

she gave everything to his work and lived only to meet

his needs."

S. E. Hedlund also wrote well of her: "What pleases and

warms my heart to think of the tranquil harbor, in which my

friend was allowed to rest his joys under the care of his

faithful companion."

Rydberg himself, in a letter to his sister Hedda Clark,

writes about his living conditions the year after his

marriage in January 1880:

"I am a sluggish letter writer, because I have to

sit at the desk so much, and even during my free time, it is

difficult for me to turn off the thoughts that then occupy

me; ...Although I am not able, but must work and exert

myself to acquire my bread, I am happy, because I have been

able to follow my inner calling, which is one of the

greatest benefits that can befall a man, and because I have

the most cordial, nicest and in every respect the best

little wife imaginable. We have a neat home, one that suits

a writer, in a beautiful neighborhood of the city.

My wife's parents and siblings with their family members

constitute a lovable circle of friendship, which I enjoy and

who show the greatest affection for me. My old society with

the Hedlund family is as intimate as it always has been, and

I have so far gained respect and kindness even in the most

extensive circles with which I come into contact, and my

writing business has gained recognition nationally in my

country. All of this means that I should feel grateful for

the higher powers that govern our lives. My gratitude also

includes you, dear, little sister, who was my benevolent

angel during the difficult days of my youth."

|

|

With this in mind, let us return to where the rumor started. As

you read, note the author's suggestive tone and his use of

overt innuendos throughout the text:

|

|

|

|

|

1928 Victor Svanberg

Associate Professor, Uppsala University

Novantiken i Den Siste Atenaren,

p. 24

Translated from Swedish

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1855,

Rydberg came to his position in the Handelstidning newspaper from a

Captain Ström at Senäte near Kinnekulle, where he was tutor to a

son in the house. In the following years, a series of letters

were exchanged between him and his former teacher, that over all

are the most important documents for Rydberg’s biography of this

time. The letters were only been accessible to me in copies,

preserved in the great collection of Rydbergiana in the Royal

Library. In the copying, certain omissions have been made and

indicated. The letters printed in Haverman’s edition are in the

most extremely edited condition.[1]

On Sept. 2nd, 1855, Rydberg responds to a letter that has not been

preserved (or copied). The older friend requites the boy’s

declaration that he often thought of his 'Yberg':

“— — as far as I remember, [has] no day gone past that I haven’t thought

of you. Perhaps our thoughts have met halfway and embraced one

another as heartily as I shall embrace you when next I meet you.

“— — wonder, if you exercise much, if you can still swim.”

“If you know, how I long to see your small, dear face. Many times

have I attempted to draw your portrait on paper from memory

without success.” He sends Rudolf 2 rdr[2]

to photograph himself and send him a picture. “I shall hang it

over my bed, give it a look every morning when I wake and keep

it until you become a grown man in order to show you how you

look as a boy.

"— — My kind Uda! You may not have been in Stockholm a week,

before you fulfilled my prayer! I have reckoned that before

September 20th I can have your picture on my wall; if it takes

longer than that I shall send a reproachful thought to your room

in Stockholm every night that shall haunt you and not give you

peace until that happens.”

Rydberg sends assurances of his “warm, never dying love.” He

says that he enjoys his new work, but not his new city. He

speaks of Rudolf’s future and returns from this to his appeal to

exercise diligently:

“Through this, one becomes healthy, strong, and supple in body

and mind. When I see you again, I will find you healthy and as

prosperous as a young rose…”[3]

During the summer of 1856, Rydberg expects a visit from the

Ströms. For this reason, Rudolf writes on November 11th, 1856:

“for every day that someone came, I imagined, before I received

word who it was, that it was Mr. Rydberg.”

He (Rudolf) has been upbraided for writing so rarely — Rydberg

believes himself neglected for new school-comrades — and he

declares now that he shall write every month and that he will

not neglect his friend:

“How could my devout friend ever believe that I could forget

Yberg, no never, never could I do that; and I have no friends

yet and likely will not ever have a real and true friend.”

In the response letter dated January 18th 1857 (Rudolf’s

letter has been lost), Rydberg takes notice of the promise of

more frequent letters:

“I shall hold you to this promise, but will, in order that it

may not become heavy and burdensome, gladly be satisfied with a

few lines every time. You have no one else to write, so write

only how you feel and your dear name there under. I save every

letter from you as a memento.” “Your portrait, which

hangs on the wall by my work-table, I consider most often during

free hours and recognize with joy every feature in your face;

even the look in your eyes has not changed. You are still my

Rudolf.”

“ — — your water-color was very nice. I keep it in a box beside

two other small pictures you drew, the one a genre-piece,

representing how you toiled in the life-belt, while I stood in

the boat before the life-belt-pole, the other a landscape— or

more correctly a seascape with forest-covered islands and the

moon.”

The following summer Rydberg thought to make a journey on foot in

Västergötland with a friend:

“since I intend to separate from them and continue the journey

on my own, in order to meet a certain little friend that I keep

more by than some other. “— — While I now write, I have your

[portrait] lying before me. But it is not the same as seeing you

in person, and I really long to hug you vigorously in my

armsonce again. I think of you daily, my best friend Uda! And do

with this letter what you said you did with my previous one.”

The last request refers to the following passage in Rudolf’s

letter: “So many times I have given Mr. Rydberg’s letter a

devout Spormosa” It is evidently a paraphrase for kiss, and

Rydberg has used a paraphrase of the paraphrase.

In a P.S., he says that he dwells upon a novel. It is

“The Freebooter on the Baltic” in which he indicates his

infatuation for a “meagerly grown boy”. On August 1st, 1857,

when Rudolf Ström receives the book and thanks him for it, he

writes that he recognizes part of its contents: In many places,

I recognize the stories Rydberg tells me of the witch-trails.”

The relations of the two friends must actually have been very

intimate. By the side of a tutor’s ordinary duties has Rydberg

taken time to give his little friend swimming lessons but also

to teach him part of his cultural history studies, hardly

suitable for a child.

In the same letter, Rydberg is invited to the Ström’s

new property, Bleckenstad in Östergotland. The boy wanted to

make the invitation as tempting as possible: “Pappa himself

(!) builds the residence-house here at home, and there it is so

furnished that Yberg can come and stay in the room beside me — —

I hope and wish so much to get to see my Yberg at Bleckenstad.”

In an undated letter, responding to one of August 15th 1857,

Rudolf explains excitedly: “I weep with joy to have such a

friend, the only one whose friendship I could previously

acquire.” One year later on August 8th 1858, Rydberg has

experiences from Norway to relate. What he has to say there

about the connection between his love and his feelings for

nature is confirmed by his contemporary poetry:[4]

“From Dovre mountain we climbed down into Romsdale. Oh, my

Uda, there you should walk by my side. — — — During the journey,

as on others, I often thought of you: a beautiful regions meet

the walker’s eyes, leading his thoughts back to a friend with

which he should want to try to live in that place.”

In the next letter, he renews the association between journeys

to beautiful regions and the friend: It is now a question of

Greece, where the poet, near the end of the year 1858, tarries

in imagination during his work on The Last Athenian, which he

mentions in the letter:

“I have big travel-plans for myself and have thought of nothing

less than a journey to Italy and Greece. But I may well put off

the journey until 1860, if I am alive then. In 1859, instead, I

shall travel to Rudolf Ström who competes with Italy and Greece

for my favor, and the first thing I shall do is take him in my

arms and the second — no the third, to drink a brorskål[5]

with him, because now he is no longer the little stripling whose

hair I could pull and spank, if I chose, but a young man that

unpunished nobody dares to be at loggerheads.”

One takes note that Rydberg has as before evaded to speak about

the kiss — but that he covets it, firmly saying to himself that

the boy has become a man. The letter concludes: “Now ten

thousand hugs and farewells”, and under his signature adds: “If

you do not write immediately, I shall haunt you in your dreams

(December 20th 1858)."

Rydberg has no difficulty intertwining that in his

love-explanations in the same manner braided into his subsequent

idealistic interest: the sharp-shooter’s movement. The Autumn

1859, when he was occupied with his brochure about a

popular-arming, based on sports-exercise in schools, he writes

to Rudolf Ström, expecting interest of him for the voluntary

marksman-movement:

“Our friendship-connection, so delightful for me and dear also

to you, could then also bear a fruit for others.”

In feeling of that the union of minds now approached its

conclusion, since its object ceased to be a child, in the same

letter he gives a melancholy look back on their old life

together:

“I still recall the time at Senäte when I working on

an astronomy problem, drew differentials and integrals and

constantly looked up my logarithmic tables, scarcely allowing

myself a night’s rest, before I solved it. But still gladly

taking time with the picture of my little slender dark-haired

boy, whose countenance the photograph you sent me, preserved and

I often looked at with a feeling of sadness. Why it should be

with one such feeling, I will not seek to investigate; I do not

want to have the whole time when we were together, again, but an

hour of the time I want to relive and have you by my side,

precisely as you were then, a little pale, skinny, but in my

opinion, a very beautiful boy. It was something in your face

that occupied me; I think about it now, moreover with the

child-expression with which it was devoutly united, was entirely

gone, when I saw you again.” (November 29th, 1859).

The letter concludes with the usual wish about a substitute

in the world of dreams for a meeting which could not happen in

the real world: “I now go to bed, perhaps to dream of you.”

|

|

|

Footnotes:

[1] [Svanberg’s footnote] Brev

II, s. 3 ff.

[2] “rdr” is short for the

former currency in Sweden, riksdaler.

[3] [Svanberg’s footnote] An

omission is indicated in the transcript.

[4] [Svanberg’s footnote:] See

“Rydberg’s Singoalla, a Study” p. 78.

[5] Brorskål,

literally “brothers’ cheers”, a drink to seal a formal bond

of friendship.

|

|

I will point out once more: the copied letters in the Royal

Library have not been censored. All the affectionate phrases

were faithfully reproduced by Rydberg's wife. In thier original

context, her husband's words are best read as signs of great affection

for the young student he had tutored and not as an erotic

expression. Susen Rydberg, of course, was aware of the

connotations of words and did not see fit to censor the

letters. Likewise, Rudolf Ström shared the letters with his

wife, and preserved them faithfully until his own death. The

evidence simply does not support the conclusion that Rydberg was

a homosexual or a pedophile. Svanberg, who created a sensation

with the accusation on the centennial of the author's birth,

appears to have seen what he wanted to in Rydberg's work. His

was a deeply personal reading. In "Strindberg and Genre" (1991),

Michael Robinson writes:

"Victor Svanberg (1896-1985) was a literary critic who

became a professor at the provincial university of Uppsala.

Some people — he himself at least — considered him daring

and radical because he stated openly that the great liberal

Swedish nineteenth-century writer Viktor Rydberg (1825-1895)

was homosexual and loved boys."

Svanberg was the first to highlight what he saw as the

underlying personal motives for Rydberg's interest in the

antiquities. According to Greger Eman, who earned degrees in

social anthropology and literature, Svanberg's motive for

highlighting Rydberg's sexuality "was based in both a general

political and sexual radicalism' with the hope that "his book

would serve as a blow to the culturally conservative

establishment". Eman concludes:

"He did so on the 100th anniversary of Rydberg's birth, a

poorly-chosen occasion, as the audience expected praises and

honorary memorials. At that time, Viktor Rydberg's name was

more acclaimed than before or since. He was not just a role

model for youth, but came to represent the whole of

Swedish literture in the 1800s from Romanticism through

Liberalism's efforts to enlighten to a foreshadowing of 20th

century expressionist painting. Against this

background, it may not be considered strange, that a few

years earlier Svanberg was forced by his supervisor,

Professor Blanck, to omit a chapter in his dissertation

where he discussed the 'homosexual' relationship between the

knights Erland and Sorgbarn (in Rydberg's masterwork

Singoalla). Blanck refused to contribute to making 'the

noble Swedish idealist' look like Oscar Wilde."*

*Svanberg,

Victor. Leva för att leva. Memoarer, Stockholm, 1970,

p. 50.

According to modern literary theory, Svanberg's personal

interpretion of the letters' contents can be explained in that

he, as a researcher, unconsciously applied his own opinions and

experiences to the text. As Professor Sjöberg points out, Greger

Eman, himself a leader in the LGBTQ movement, indirectly

admitted as much, when he said:

"In his memoirs, Leva för att leva (1970), Svanberg

admitted his own attraction to men. It is likely that,

thanks to his own homosexuality, he was well positioned to

do what would today be called a queer reading of Rydberg's

half-queer visions and the many aesthetic descriptions of

the

athletic

male

body."

To make his

case, Svanberg, isolated passages in a series of friendly

letters between the sickly adolescent and his former tutor,

citing them as the basis for his theory of a same-sex attraction

between Rydberg (then 27) and teenager Rudolf Ström. In the

letters, Rydberg expresses great concern for the boy's

well-being and health, encouraging him to get outdoors and

exercise, as they had once done together. He also requests a

picture of the boy, and praises his artistic talent. In

response, Rudolf laments that he has no other friends because of

his poor health, and longs for Rydberg, now a rising cultural

figure, to visit him. Considering Rydberg's own tragic childhood

and his repeated bouts of ill-health and depression, it seems

more likely that Rydberg saw himself in this young man, feeling

the need to befriend and encourage the boy in a way that no one

had done for him at that age. Rather than a same-sex attraction,

Rydberg more likely felt deep sympathy for this young man's

plight, having overcome similar hardships in his own life.

Notably, when Rydberg first received the offer from Sven

Hedlund to work for the newspaper in Gothenburg where he

would remain employed for many years, Rudolf's father,

Captain Ström offered to extend his position as tutor for

another year, causing Viktor Rydberg to write his brother

Carl, a teacher who had recommended him to the Ströms,

asking for advice in a letter dated February 2, 1855:

|

"When I showed the letter to Captain Ström and asked him

what he thought, what I should do, he explained that if

I wanted to remain as a tutor for Rudolf, I could

definitely expect to accompany Rudolf to Stockholm next

September, where we would live with the

expedition-secretary[1]

Hellman, and I would receive room and board for my

supervision of Rudolf's studies. Thus Providence has now

opened two prospects for me, when just before I thought

I had none. But in this dilemma, what I shall decide on,

I do not yet know, and I now want to claim your

brotherly friendship for good advice. Before that, I

cannot write to Master Hedlund, but ask you to convey my

cordial greetings and thanks for his offer.

"Much speaks both for and against one and the other of

the proposals. I have become very attached to Captain

Ström's family and to my little pupil, who is an

unusually kind boy; his studies could possibly suffer if

he had to change tutors at this particular juncture. But

if, on the other hand, I have the indisputable advantage

of changing places, this apprehension must give way,

because a poor chap such as myself must seize the

opportunity in flight—; otherwise it might never be

offered again."

[1]

expeditionssekreterare:

"expedition-secretary", until the end of 1878,

a designation for the second highest official in the State

Department.

|

See also:

The 'Outing' of Viktor Rydberg

|

|

|