|

Niddhöggr, Yggdrassils Askr,

and the Swan Song of Cyngus

by Dr. Christopher E. Johnsen

© 2014

[HOME]

Death and birth are the two most fundamental parts of our experience on earth – both our own, and others’. Our multiple planetary cultures have created innumerable rituals, beliefs and myths about these two very deep mysteries.

The Swan Song (in ancient Greek: κύκνειον άσμα) is a metaphorical phrase for a final gesture, effort, or performance given just before death and refers to an ancient belief that swans sing a beautiful song in the moment just before death, having been silent during the rest of their lifetime. This belief was widespread in Ancient Greece by the 3rd century BC, and was repeated later in Western poetry and art.

In Greek mythology, the swan was a bird consecrated to Apollo (the Greek Odin), and it was therefore considered a symbol of harmony and beauty and its limited capabilities as a singer were sublimated to those of songbirds.

Aesop's fable of "The Swan Mistaken for a Goose" incorporates the swan song legend:

"The swan, who had been caught by mistake instead of the goose, began to sing as a prelude to its own demise. His voice was recognized and the song saved his life.”

In Aeschylus' Agamemnon from 458 BC, Clytemnestra compares the dead Cassandra to a swan who has "sung her last final lament". Plato's Phaedo records Socrates saying that, although swans sing in early life, they do not do so as beautifully as before they die. Aristotle also noted that swans "are musical, and sing chiefly at the approach of death". By the third century BC the belief had become a proverb.

Ovid mentions it in "The Story of Picus and Canens":

"There, she poured out her words of grief, tearfully, in faint tones, in harmony with sadness, just as the swan sings once, in dying, its own funeral song.”

The swan was also described as a singer in the works of the poets Virgil and Martial. Swans usually mate for life, unless there is a nesting failure. And if a mate dies, or is killed by a predator, the remaining mate will take up with another; however, if all goes well in the pairing, they will stay together for life.

In Norse Myth, we find Swans are very prominent. There are two swans that drink from the sacred Well of Urd. The water of this well is so pure and holy that all things that touch it turn white, including this original pair of swans and all others descended from them (according to Timothy Stephany – a moon picture of 2 swans in the moon). The poem Völundarkviða, or the Lay of Völund, in the Poetic Edda, also features swan maidens who are 3 dises (Rydberg says they are Sif, Idunn and Sigyn, I believe). We find mention of the “swan road” in Beowulf (swan-rād (Beowulf 200 a)) which I would imagine was a great name for the Milky Way since Cygnus is very prominent on it and it was also the road of the dead.

The Germanic Matres and Matrones, are female deities venerated in North-West Europe from the 1st to the 5th century AD depicted on votive objects and altars almost entirely in groups of three from the first to the fifth century AD have been proposed as connected with the later Germanic dísir, valkyries, and norns, which potentially descended from them, or perhaps were related depending upon how great the antiquity of the Norse Myths really are (in my personal view – probably thousands of years older than they are given credit for).

The Glastonbury zodiac is a great circle of landscape effigies 12 miles wide, formed by natural hills, old tracks, field boundaries and rivers in Glatonbury, a small town in Somerset, England. There are descriptive place-names and related folklore which bring to mind a zodiacal origin. Artist and sculptor Katherine Maltwood discovered it in the 1920’s by looking at local survey maps, searching for geographical features and place-names to get ideas for a book she was illustrating and she began to see landscape effigies on the survey maps. First she saw a lion around Somerton, a giant made of Dundon Beacon and Lollover Hill, and near Athelney a 'Girt Dog', noted in local folklore. She believed that the heavens were mirrored on the ground, and that she discovered a prehistoric terrestrial zodiac. She found a number of other effigies personifying the twelve zodiacal constellations, and published this in A Guide to Glastonbury's Temple of the Stars, in 1934.

|

|

In Glastonbury there is a swan effigy that straddles two signs of the zodiac. One is Aquarius, defined by her as a bird - the Phoenix - a symbol of rebirth, defined by hills and high ground, which forms its curled head and beak. The other sign is Pisces at Wearyall Hill, which was seen by her as one of two twin fish effigies. These two zodiac houses cover the periods between, respectively, 22 January to 21 February (Aquarius) and 22 February to 21 March (Pisces). The first embraces the feast of Brigid, held on February 1st , as well as the season that migrating swans journey north to their breeding grounds in Iceland and the Arctic regions.

Brigid's feast day embraced the time that swans migrated North and in the Scottish Western Isles it was believed that swans were responsible for carrying the souls of those who had died over the winter months. The connection between swans and death is very ancient for swans' wings have been found beneath the burial of a child lying next to the skeleton of a woman, probably his mother, at the 7,000-year-old Vadbaek cemetery in Denmark, while swan pendants have repeatedly been found in Upper Palaeolithic grave sites in Siberia, which date to c. 13,000 BC. So, is Glastonbury's swan effigy to be seen as a soul-carrier, taking the deceased beyond the land of the living to the Celtic Otherworld, envisioned as an Island of the Dead existing in the Western Sea? Glastonbury was originally called Ynys Witrin, meaning the Glass Isle, a place synonymous with such an otherworldly location.

|

|

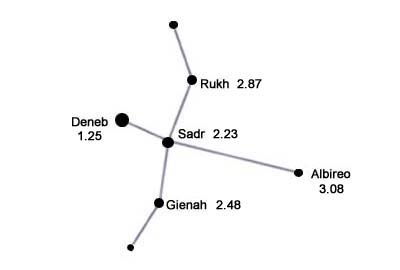

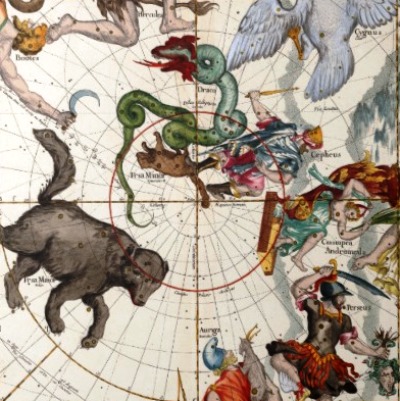

In astronomy, as mentioned above, Cygnus the swan, is right on the Milky Way – right at the cosmic rift where Cygnus, also known as the Northern Cross, looks like it is flying on the Milky Way towards Sagittarius. As we know it is extremely likely that the Milky Way was seen as a road or river where the dead crossed over or traveled upon to reach the land of the dead. Cygnus is located at the northern-most reaches of the Milky Way, reflecting how migrating swans were seen to journey each spring over the earth.

Worldwide in many mythologies, Cygnus was seen as the entrance and exit to the sky-world and perhaps the original location of heaven. The extreme north was where the dead went in the afterlife and they reached it by going to the Pole Star along the north-south meridian line, which splits the heavens in two along its longitudinal zenith. This cosmic axis of the Northern Hemisphere was seen as linked with the axis mundi of the terrestrial world, via a sky-pole, which has featured extensively in shamanic practices across Europe and Asia.

The Tungus reindeer shamans of Siberia constructed sky-poles topped by swans, up which they would climb in order to reach the sky-world. The Sami shamans in the far North of Sweden, Norway and Finland also practiced similar shamanism where they would dry the Amanita muscaria mushrooms on strings over the hearth and they would enter and exit their dwellings via these cosmic birch poles (progenitors of Santa Claus). The shaman would enter a trance state and rise up the axis mundi, represented by the birch pole and enter the Milky Way via Cygnus a few hours before dawn.

|

|

Cygnus was at the northern celestial pole from 16,000-13,000 BC, and is shown in Paleolithic cave art as early as 15,000 BCE as a bird on a pole in the painting of the Dead Man (which I have mentioned in my posts before in relation to Audhumla, Ymir and Buri) at Lascaux cave. The 11,500-year-old megaliths at Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, target Deneb, Cygnus's brightest star, and this was probably a complex where the dead were placed on top of the “t-shaped” structures to be consumed by vultures (Cygnus was probably seen as a vulture in Egypt and Mesopotamia and was part of a Snake and Vulture cult that was passed down from earlier vulture cults that sacrificed their dead to Vultures on pillars and raised structures to be ex-carnated (i.e. eaten by vultures and the bones buried) eventually to Egypt where they were featured on the Pharaohs’ nemes headdresses and represented the maxim “as above: so below”).

Similar megalithic structures and alignments are to be found at Avebury, Wayland’s Smithy, Callanish and Newgrange and according to Andrew Collins (who I have relied heavily upon in this essay) in Egypt at Cairo (Cygnus fits the pyramid alignments better than Orion).

We know that the pole star was not always Polaris, at 2800 BC, it was a star in Draco, Thuban, (due to the precession of the equinoxes) and earlier, around 9500 BC, there was no pole star, and the constellation Cygnus circled around an empty hole in the sky which we could think of as the entrance to the otherworld or perhaps Val-halla, where the Valkyrie swan maidens would serve the honored dead their Cosmic Mead from the Milky Way.

In 11,000 BC, the pole star was Vega in the constellation Lyra – in Sumerian Raditartakhu - and was one of three birds (Lyra, Aquila and Cygnus) attacking the god Marduk (the constellation Hercules) and Lyra was also known as the “Eagle of the Arabians” but Lyra was also known as the “falling grype” or vulture. The old claws of Scorpius which became known as Libra, were also once known as a celestial serpent or dragon.

So in 9500 BC there was just a hole in the center of the northern circumpolar stars, where now we see the Big Bear and the Little Bear and the Lynx and all those other constellations. Many of these ancient cultures built huge monuments in stone that tracked the stars. The time period when these structures were erected is uncertain. Since the Vedic, Greek, Babylonian, Egyptian and Norse myths have survived and been transmitted for thousands of years, and we still can see ancient cave paintings from 13,000 to 30,000 years ago (Lascaux cave may have been chipped away to form a representation of the Milky Way in stone – its layout closely resembles the Milky Way), it seems probable that myths could have been transmitted from 9500 BC to a few thousand years later, particularly if the population at the time was much smaller. I believe that it is possible that we see the remnants of incredibly ancient star worship in the myths that we are investigating today from a few thousand years ago.

This was probably the original conception of the entrance to the underworld and later when the precession of the equinoxes changed the polestar, the ideas changed too and the concept of Yggdrasils askr developed. If we look at Eirikr Magnússon’s work, Odin's Horse Yggdrasill, he says we see two forms of the name — “We meet it in the form of Yggdrasill [Völuspá 20] and in the form of Yggdrasils askr or askr Yggdrasils” – “This term is composed of two elements Ygg, grammatically Yggs, and dra-sill. Ygg is the stem of Yggr a palatal of uggr, fear, awe, meaning Awer the Terrible and is one of Odin's many names.” “Drasill is an exclusively poetical word meaning a horse a steed. Yggdrasill therefore means Awer's horse or the horse of Awer Hence since askr means an ash, ash-tree, the longer term askr Yggdrasils signifies the Ash of Awer's horse or the Ash of the horse of Awer. This is the only possible rendering of the term due regard being had to grammar.” – “I go into these obvious and simple details in order to remove all doubt as to the correctness of this translation and to make it quite clear at the same time how utterly at fault is the rendering of the term in the Corpus Poeticum Boreale where throughout it reads the Ash Ygg's steed a genitive governed by a noun being treated as in apposition to that noun!” –

This is a fairly long paper but he basically says that “Yggdrasils askr” is the correct term not Yggdrasill and that the late, common (mis)conception is that it means the “gallows” where Odin was hanged. In a footnote he also states “The real point here seems to be this: the gallows tree from which the hanged is suspended is a horizontally rigged up beam from what roots such a tree springs no one knows since it has got no soil even to stand in. The appearance of a gallows (TT) naturally suggested to an imaginative race the outlines of a horse hence the kennings for gallows into which words meaning 'horse', 'steed' do enter.”

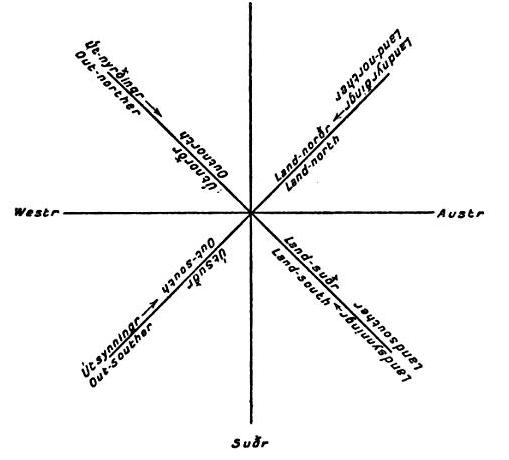

This goes on and on and is GREAT – you have to read the whole thing – but finally, he writes that everything he just wrote is wrong and the original conception can’t possibly mean “gallows” and what he just wrote is a mistake that has been perpetuated from faulty translation down the ages and finally says “Askr Yggdrasils we have seen means the ash of Odin's horse. On that point all must be agreed. The myth knows of only one horse belonging to Odin and that the best of all horses. This was the eight footed steed Sleipner of which so little has been made hitherto.” And further on “And Sleipner Odin's eight footed horse means unquestionably as I shall show presently the WIND.” – “The ancient Northmen believed that wind could blow from only eight points of the horizon compass” He follows this with a diagram – pg. 53 – and shows the myth could only have developed in Western Norway due to the eastern mountains and the sea to the West.

He says ultimately that “Yggdrasils” is a kenning for “Sleipner” and the Askr is Sleipner’s ash. The question I ask myself about it thus becomes “What windy horse in the sky would live under a canopy of starry leaves and fruits?” Pegasus is the only one that comes to my mind.

“The great world ash is mentioned in only two poems of the Older Edda the Völuspá and Grímnismál and in the prose paraphrase of these songs in the Younger Edda in Codex Regius of the Older Edda the name of Yggdrasill is applied to it only once but that of askr Yggdrasils seven times.”

Yggdrasils askr would then be more or less like a horse’s hitching pole rather than a gallows. Pegasus is visible in the autumn and rides around the pole star as if the pole star was a hitching pole for the windy horse. The Milky Way could not possibly be the ash’s trunk – it was a road or a river, not a tree trunk, and it is curved. But it could be seen as the roots of the tree since there are 3 parts to the Milky Way and three roots to Yggdrasils ash. Roots can curve. The axis mundi was the invisible pillar that held up the heavens or as Hohenöcker (1973) says “In every work of Germanic mythology one reads of the gods that they were called Aesir, i.e. ‘Pillars of the world.’”

|

|

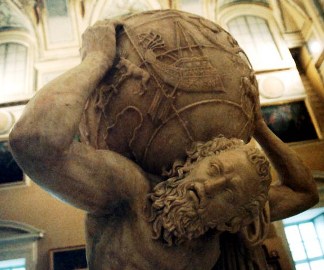

Professor Willy Worth (1966) describes the outstretched arms of Atlas as the “volutes” that we see on the Irminsul (the golden apples of the Hesperides are both the stars and multi-dimensionally they are also the “fruits” or mushrooms that grow only beneath certain trees, and are the same as Idunn’s golden apples of eternal youth). This is the Germanic world pillar.

Jurgen Spanuth says in his Atlantis of the North (pg. 92) “Atlas, the god of the world pillar, is said to hold up the heavens with his two upraised arms” and “The Romans called such pillars ‘metae’. This was also the word for the turning post in the circus, round which the chariots had to swing. Since the distance covered in the race was reckoned by ‘metae’ they serve also as measuring posts, hence their name, from the Latin metri (Greek metrein), to measure. The metae were, then, both turning posts and measuring posts. The use of the same term for the heaven-pillars shows that they were similarly held to measure the revolutions of the heavens. Likewise in Völuspa (7.2), the heaven-pillar or world-tree is called mjöt-viðr, i.e. ‘measuring tree’. “

|

Thus, Draco is probably Nidhöggr since it is a very old constellation and also a true Wyrm and I believe that Ratatoskr is the little bear with the long tail (since long tails don’t exist on bears) Ursa minor. They both revolve around Polaris but Draco is closer to the Milky Way and could be envisioned as lower down the trunk while the squirrel’s tail is at the very tip. Polaris is the tip of the canopy and as you go out further away from it, it is as if you are looking up the trunk, the lower down on the tree’s trunk you are, the wider it gets, until you get to the roots which are represented by the Milky Way. The Norns dish out the white milky substance from the moon well and drip it onto the Milky Way (the roots of the ash tree) to keep it white. The stars are the fruits that Hoënir, the stork god, delivers to the mother that has just conceived a child and implants in her belly. Nidhögg bites the roots and Ratatosk is at the top. One of the three birds (Cygnus, Lyra or Aquila) could be Odin as the eagle at the top from Grímnismál and one of the others the falcon on its beak.

Well, all said and done this is conjecture but it all works conceptually. I know it was a pretty long essay this time, but it would have been difficult to put this whole set of ideas into a small post. Hope you enjoyed it!