The Complete

Fornaldarsögur Norðurlanda

Legendary Sagas of the Northland

in English Translation

Both the family and the kings’ sagas, as well as other Norse sources, offer a good deal of evidence suggesting that the fornaldarsögur, or similar prose narratives, were told orally by Icelanders both before and after writing became common in the twelfth century. Sturlu þáttr, from the Sturlunga saga compendium (1946), contains a description of such oral storytelling. It records the following tale about Sturla Þórðarson, who journeyed to Norway in the mid-thirteenth century. Sturla undertook his trip hoping to restore his standing with the king, to whom he had been slandered. As fate would have it, Sturla, though gaining access to the royal ship, found the king displeased with him, and the Icelander was lodged in the forward part of the vessel away from the king (vol. 2:232-33).

And when the men lay down to sleep, the king’s forecastleman asked who should entertain them. Most remained silent at this. Then he asked: “Sturla the Icelander, will you entertain us?”

“You decide,” says Sturla. Then he told Huldar saga, better and more cleverly than any of them who were there had heard before.

Many thronged forward on the deck and wanted to hear it clearly, so that there was a great throng there.

The queen asked, “What is that crowd of men on the foredeck?”

A man says, “The men want to hear the saga that the Icelander is telling.” She said, “What saga is that?”

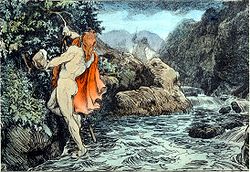

He replied, “It's about a great troll-woman, and it is a good story, and it is being well told.”

The king told her to pay no heed to this but to sleep. She said, “I think this Icelander must be a good man and much less to blame than he is reported to be.” The king remained silent. People went to sleep for the night. The following morning there was no wind, and the king's ship was in the same place. When the men were sitting at table during the day the king sent to Sturla some dishes from his table. Sturla's messmates were pleased as this, and said, “Things look better with you here than we thought, if this sort of thing goes on.”

When the men had eaten, the queen sent a message to Sturla asking him to come to her and have with him the saga about the troll-woman. Sturla went aft to the quarterdeck then and greeted the king and queen. The king received his greeting shortly but the queen received it well and easily. The queen then asked him to tell that same story that he had told in the evening. He did so, and told the saga for much of the day. When he had told it, the queen and many others thanked him and understood that he was a knowledgeable and wise man.

Although individuals like Sturla Þórðarson

may have been famed as raconteurs of fantastic stories such as the lost

Huldar saga, much remains unclear about the provenance and the

transmission of the fornaldarsögur. Even the naming of this group of

texts has caused confusion. The term “sagas of antiquity” was coined by

the first scholarly editor, presumably because the tales are set mostly

in the ancient pre-Viking and early Viking past, that is, from the fifth

to the tenth century. What the medieval Icelanders called these sagas is

not known, but, in modern times, there have been numerous attempts to

name and categorize all or parts of the fornaldarsögur. Groupings have

alternately been referred to as “legendary sagas,” “mythical-heroic

sagas,” or “legendary fiction,” and other rubrics, such as “Viking

romances” and “Viking sagas,” have been proposed. These latter

suggestions reflect the fact that many of the texts deal with Viking

forays; some of them are set in the west, as far away as Ireland, but

most take place in the East (including Finland, Bjarmaland, and

Garðaríki-Russia).

Stephen A. Mitchell, in Heroic Sagas and Ballads (1991), chooses to

stick with the term fornaldarsögur. To this end he delineates (in

chapter 2, “Definitions and Assessments”) five traits that contribute to

a definition of the texts: grounding in traditional heroic themes, their

fabulous nature, inclusion of verse, distinct temporal and spatial

frames, and a tendency toward monodimensional figures. Traditionally,

scholars in search of ancient mythic and historical information have

been the primary investigators of these texts. Such an exploration is a

time-honored pursuit. The fornaldarsögur have supplied numerous pieces

of information crucial to the unfinished jigsaw puzzle that forms our

understanding of early Scandinavia.

Halldór Hermannsson, Bibliography of the Sagas of the Kings of Norway and related sagas and tales, 1894.

Huldar saga is mentioned in the Sturlunga saga (Vigfusson's ed. II. p. 270), but it has not been preserved in writing. There exists, however, a Huldar saga in three recensions, all of which date from the l8th century, but it probably has no connection with the old saga. One of these recensions has been printed in Icelandic (recension II; ascribed to Jón Espólin), and another in Danish version (recension I; a late 18th cent. MS. of this recension is in the Fiske Icelandic collection).

Sagan af Huld hinni miklu og fjolkunnugu trölldrotningu.

Akureyri, (Oddur Bjornsson), 1911. 8°. pp. 60. Danish.—Hulde. Fragment af en romantisk Fortælling, hidtil

udtrykt [!], oversat af det gamle Skandinaviske ved W. H. F. Abrahamson. In Det Skandinaviske Literatur-Selskabs

Skrifter. 1805. I. Bd. pp. 262-334.

Maurer, Konrad. Die Huldar saga. Aus den Abhandlungen der k. bayer. Akademie der Wiss. I. Cl. XX. Bd. II. Abth. [pp. 223-321]. München 1894. 40. pp. 99.

Review: Lit. Cbl. XLV. 1894. coll. 1774-75, by E. Mogk.

“'Die Huldar Saga' by Konrad Maurer, a reprint from the Proceedings of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, is an admirable and exhaustive study of one of the latest and perhaps least important of the Icelandic sagas. Prof. Maurer’s researches as to the origin, age, and value of this apocryphal work lead to some interesting observations on the peculiar literary condition of Iceland at the present day, as manifested in the still vigorous vitality and often too exhuberant growth of the sage.”

Huldar saga hinnar miklu (manuscripts)

Huld. Fragment of a romantic tale translated from the Old Scandinavian by Capt. W.H.F. Abrahamson, 1805. Skandinaviske Literatur-Selskabs Skrifter. 1805. I. Bd. pp. 262-334.

Die Huldar Saga by Konrad Mauer, 1894 (scanned version).

Weitere Mittheilungen über die Huldar saga by Konrad Mauer, 1894 (scanned version).

Special thanks to my friend Carla O'Harris for inspiring and developing this line of research.