Medieval Text Messaging

and Early Encryption1, 2

This inscription from the early stone age found in an Orkney Isle burial chamber reads:

"Written by the most rune-literate man west of the sea."

[HOME]

|

The knowledge of cypher runes is best preserved in Icelandic manuscripts from the 17th and the 18th centuries. Icelandic scholars devoted several treatises to the subject. The most notable of these is the manuscript Runologia by Jón Ólafsson (1705–79), now preserved in the Copenhagen Arnamagnæan Collection, illustrating numerous cypher runes and runic cyphers. Jón's treatise presents the Younger Futhark in Viking Age order which means that the m-rune precedes the l-rune. This small detail is of utmost importance for the interpretation of Viking Age cypher runes. In the 13th century, the two runes had been transposed, so that l preceded m. Since the medieval runic calendar used the post-13th-century order, the early runologists of the 17th and the 18th centuries thought that the l-m order was the original. As they discovered, the order of the runes is of vital importance for the interpretation of cypher runes. |

||

|

CRACKING THE JÖTUNVILLIR CODE |

||

|

In April 2013, Runologist K. Jonas Nordby successfully

cracked the jötunvillur code, a runic encryption which had

previously baffled linguists and historians. His PhD

research has taken him to several countries to analyze runic

inscriptions dating back as far as 800 AD. Nordby was the first

person to study all of the runic code finds in Northern

Europe, around 80 inscriptions in all. |

||

|

||

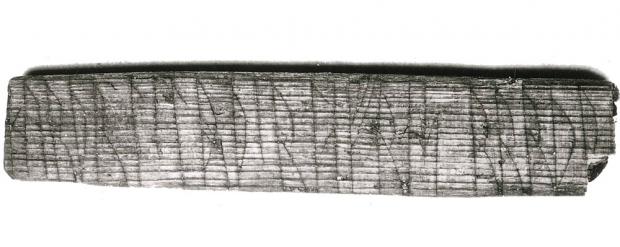

| Two men, Sigurd and Lavrans, carved their names in code and again in standard runes on this stick (above) found at Bergen Wharf and dating from the 13th century. This was the key Nordby used to crack the jötunvillur code. (Photo: Aslak Liestøl/Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo) | ||

|

|

||

|

Medieval Norse people carved runic inscriptions onto sticks of wood, stones and other objects. They have turned up all over Scandinavia, the British Isles and other places where runes were used, often etched on personal items such as weapons, brooch pins and combs. Personal names occur frequently. Among the many examples of ancient runic writing for study, we find that the use of code was common. “It was very common to use codes. Much of the population mastered them. That’s why I think they were something people picked up at the same time they learned the runic alphabet. If you had learned to read and write, you had also learned codes,” says Nordby. Knowledge of this system of written communication could be transferred from generation to generation by linking it to games, poetry, and codes, Nordby suggests. Even as we do today, when teaching children language in spoken and written forms, using time-tested games, songs and even simple cyphers. The rune poems, which appear in most of the Scandinavian languages, are another example of this kind of ancient Nordic popular instruction. Some think of it as a kind of medieval text message, encrypted to be read by a select few whom you knew understood the code— perhaps, but its also more than that. "We have little reason to believe the runic codes were used to conceal sensitive information. People often wrote short, routine messages," says Nordby. He continues, “I think the codes were used in play and for learning runes, rather than to communicate.” As with the rune songs, Nordby thinks that the Vikings may have memorized rune names with the help of the jötunvillur code. All runes have names, and the jötunvillur code works by exchanging the rune sign with the last sound in the rune’s name. For example, the rune for the letter m is called “maðr” so it is encoded with the rune for R. The difficulty comes determining exactly which runic letter the code intends, since many runes end in the same sound. "The thing that solved it for me was seeing these two old Norse names, Sigurd and Lavrans, and after each of them was this combination of runes which made no sense," said Nordby. The jötunvillur code is found on only nine inscriptions, from different parts of Scandinavia, and has never been interpreted before. So far, what Nordby calls his "Rosetta stone" is the only place in which it is possible to be sure what the jötunvillur code says, although he believes another rune stick may well have been inscribed with the name Thorstein, and another with the name Einar. The sticks on which the code has been written, said Nordby, are "everyday objects, so you often find names on them, either because they used them to communicate that it was something they wanted to keep or sell, or for practising writing, or because they were talking about people so names occur frequently". Many rune sticks have been excavated in Scandinavia, dating back to the 1100s and 1200s, he said. Just a few use codes, and even fewer use the jötunvillur code. "They were used to communicate, like the text messages of the Middle Ages – they were for frequent messages which had validity in the here and now," he said. "Maybe a message to a wife, or a transaction."

|

||

|

|

||

|

A message (c. 12-13th century AD) written in

cypher-runes which simply reads “Kiss me” is etched into a piece

of bone found in Sigtuna, Sweden. The code known as "Ice

Runes" dates from medieval Scandinavia. (Photo: Jonas Nordby). |

||

|

The rune codes were not just used for learning. Nordby

thinks the existing examples also indicate a whimsical use of

writing in the Viking Era and the Middle Ages. Coded messages such

as “Kiss me” demonstrate that the use of code was not limited to

political intrigue. Many messages in runic code include a

challenge to the reader to crack the code. “Interpret these

runes” was a common inscription. “People challenged one another with codes. It was a kind of competition in the art of rune making. This testifies to a playfulness with writing that we seldom see today,” says Nordby. Nine of the 80 or so coded runic writings that Nordby has examined are written in the jötunvillur code. The others are written in cypher runes or with the Caesar cypher, a substitution cypher involving a shifting of letters a few spaces backward or forward in the alphabet. The latter two codes have been understood for some time.

|

||

|

||

|

Another rune stick found at Bergen Wharf. Lines in

the beards of these figures comprise a message written in

cypher runes. (Photo: Aslak Liestøl/ Museum of Cultural

History, University of Oslo)

|

||

|

Clearly cypher-runes were used for much more than communication. They challenge the reader, demonstrate skill, and testify to a joy in reading and writing. "We still know very little about the use of runic codes, so that each new piece of information is important," concludes Nordby. |

|

Cypher, 14th century, a less common alternate spelling of cipher, still in use in English. From Old French cyfre, cyffre (French chiffre), ultimately from Arabic صفر (sifr, “zero, empty”), from صفر (safara, “to be empty”). Compare zero. |

||

| Rune, Old Norse rúni: secret, hidden lore, mystery [presumes a lost strong verb, rúna, raun, meaning to enquire; the original notion is scrutiny, mystery, secret conversation]; Gothic runa; Anglo-Saxon rún = a 'rowning' mystery, but also = writing, charter; cp. Old English to rown, German raunen. In Scandinavian writers and poets rún is chiefly used of magical characters, then of writing. |

[HOME]