The Poetic Edda: A Study Guide

The Speech of the Masked One

[PREVIOUS][GRIMNISMAL 31][NEXT]

[MAIN][HOME]

I. “...under one dwells Hel”

As we have seen, the lower world is divided into two distinct halves: the warm, green fields of Hel in the South and the cold, dismal Niflhel in the North. Mimir's Grove (Hoddmimis holt) lies between them. As demonstrated in the general commentary to this stanza, the root extending to Urd’s well best corresponds to the root “with Hel” . Clearly, it is not Mimir's well, and it is distinct from the northern root of the world-tree inhabited by giants, ogresses, dwarves, dark-elves, and the corpses of men (Hrafnagaldur Óðinns 25).

Plainly stated, Urd’s well is located in the green fields of Hel in the southern half of the underworld. Urd's thingstead, where the gods meet daily Grímnismál 29 and 30, is located in the warm southern regions on the great fields and grasslands of the lower world. To the north, across Nidi’s mountains (Nidafjöll) lies Niflhel (Mist-Hel) in the ancient wastes of Niflheim, the birthplace of the frost-giants and the home of the well Hvergelmir ("Roaring Kettle"), the mother of all waters, Grímnismál 27. Mimir’s well and realm occupy the mild, windless space between them, "where Ginungagap once was" (Gylfaginning 15), at the very center of all Creation. Together, these three realms form the underworld of the Old Norse cosmology. Midgard lies directly above them. And Asgard up above it ("upp í Goðheim", Sonatorrek).

Urd and her sisters are known collectively (but not exclusively) as “Norns”. They determine the fate of all living beings. Even the Æsir are subject to their edict, as Baldur’s death demonstrates. Odin himself is unable to prevent his son's or his own impending fate. Nor can he escape his own fate.

Yet, despite the three Norns' powerful position, we find relatively little information about them in the lore. The origin of the Norns is nowhere narrated. Their role is never clearly defined either in Snorri's Edda or the poems of the Poetic Edda. They remain shadowy figures shrouded in mystery. What we learn of them, we must glean from the various references to them. First, there are more than three Norns.

Fafnismál

|

Sigurðr kvað: |

Sigurd said: 12. "Tell me Fafnir, as you are said to be wise and know many things; who are those Norns, who help in need, and choose children for mothers." |

|

Fáfnir kvað: |

Fafnir said: 13. "Very diverse born I take those Norns to be; they have no common ætt, some are of the Aesir, some are of the elves, some are Dvalin's daughters." |

See Karen Bek-Pedersen, Are the Spinning Norns Just a Yarn?, 13th International Saga Conference, 2006

|

The Wierd Sisters

Foremost among

the Norns is Urd (Wierd) accompanied by her two sisters. Urd and her sisters,

Verdandi and Skuld, are named in Völuspá 20.

|

Þaðan koma meyjar |

Then came maids Much knowing Three out of the sea (or hall) That stands under the tree; Urd, one is named, another Verdandi, —scoring on boards— Skuld is the third; They lay down laws (lög). They choose life for the children of men, speak destiny (örlög). |

The two manuscript copies of this verse vary. In Codex Regius, the Norns are said to emerge from a sal (“feasting hall”), while in the Hauksbok manuscript, Urd and her sisters emerge from a sæ (“sea”) which stands beneath the world-tree. According to this verse, the Norns skáru á skíði, "etch or score pieces of wood", as a means of divination. They choose the fates of men, and determine the course of their lives. Snorri elaborates on this point in Gylfaginning 15, informing us that perform this important function at the birth of a child:

| Þar stendr salr einn fagr undir askinum við brunninn, ok ór þeim sal koma þrjár meyjar, þær er svá heita: Urðr, Verðandi, Skuld. Þessar meyjar skapa mönnum aldr. Þær köllum vér nornir. | A hall stands there, fair, under the ash by the well, and out of that hall come three maids, who are so called: Urdr, Verdandi, Skuld; these maids determine the period of men's lives: we call them norns. |

The function of the Norns to determine the fate of men is alluded to several times in the lore. Twice, we find instances of Norns visiting a child at birth and pronouncing his fate. One occurs in Helgakvida Hundingsbana I:

|

Nótt varð í bæ, |

2. It was night, Norns came who would shape the life of the prince They decreed him a prince, most famed to be, and of leaders accounted best. |

|

Sneru þær af afli |

3. With all their might they spun the fatal threads, that he should break burghs in Bralund. They stretched out the golden cord, and beneath the moon's hall fixed it in the middle. |

|

Þær austr ok vestr |

4. East and west they hid the ends, where the prince had lands between; Neri's kinswoman towards the north cast a chain, which she bade hold forever |

The second instance, partially euhemerized, occurs in the

Þáttr of

Nornagestr, ch. 11, which describes the Norns as visiting völvas who

bestow gifts on a child at birth and predict his future.

Þáttr of Nornagestr, ch. 11

|

Þar fóru þá um landit

völur, er kallaðar váru spákonur ok spáðu mönnum aldr. Því buðu

menn þeim ok gerðu þeim veizlur ok gáfu þeim gjafir at skilnaði.

Faðir minn gerði ok svá, ok kómu þær til hans með sveit manna,

ok skyldu þær spá mér örlög. Lá ek þá í vöggu, er þær skyldu

tala um mitt mál. Þá brunnu yfir mér tvau kertisljós. Þær mæltu

þá til mín ok sögðu mik mikinn auðnumann verða mundu ok meira en

aðra mína foreldra eða höfðingja syni þar í landi ok sögðu allt

svá skyldu fara um mitt ráð. In yngsta nornin þóttist of lítils

metin hjá hinum tveimr, er þær spurðu hana eigi eptir slíkum

spám, er svá váru mikils verðar. Var þar ok mikil ribbalda

sveit, er henni hratt ór sæti sínu, ok fell hún til jarðar. Af þessu varð hún

ákafa stygg. Kallar hún þá hátt ok reiðiliga ok bað hinar hætta

svá góðum ummælum við mik, --"því at ek skapa honum þat, at hann

skal eigi lifa lengr en kerti þat brennr, er upp er tendrat hjá

sveininum." Eptir þetta tók in

ellri völvan kertit ok slökkti ok biðr móður mína varðveita ok

kveykja eigi fyrr en á síðasta degi lífs míns. Eptir þetta fóru

spákonur í burt ok bundu ina ungu norn ok hafa hana svá í burt,

ok gaf faðir minn þeim góðar gjafir at skilnaði. Þá er ek em

roskinn maðr, fær móðir mín mér kerti þetta til varðveizlu.

|

At that time wise women (völur) used to go about the country.

They were called 'spae-wives,' and they foretold people's

futures. For this reason people used to invite them to their

houses and gave them hospitality and bestowed gifts on them at

parting. |

The heathen practice of visiting wise-women bestowing gifts on a child at birth continued to find expression several hundred years after the heathen era. A remarkably similar episode occurs at the beginning of the fairy-tale Dornröschen (Briar-Rose or Sleeping Beauty), first recorded in the 1800s:

“The Queen had a little girl who was so pretty that the King could not contain himself for joy, and ordered a great feast. He invited not only his kindred, friends and acquaintance, but also the Wise Women, in order that they might be kind and well-disposed towards the child. There were thirteen of them in his kingdom, but, as he had only twelve golden plates for them to eat out of, one of them had to be left at home. The feast was held with all manner of splendour and when it came to an end the Wise Women bestowed their magic gifts upon the baby: one gave virtue, another beauty, a third riches, and so on with everything in the world that one can wish for. When eleven of them had made their promises, suddenly the thirteenth came in. She wished to avenge herself for not having been invited, and without greeting, or even looking at any one, she cried with a loud voice, "The King's daughter shall in her fifteenth year prick herself with a spindle, and fall down dead." And, without saying a word more, she turned round and left the room.”

Throughout the Poetic Edda, we find numerous references to the Norns’

ability to shape the fates of men, instilling them with irresistable

desires to fullfill the destiny laid out for them:

Grougaldr 4

|

langir eru manna munir, |

“long last the yearnings of men, if it comes to pass that your wish be granted, then Skuld's decree is at fault.” |

The decree of the Norns is absolute. One’s fate cannot be avoided. In Hamðismál, Guðrún incites her sons to avenge the death of their sister Svanhild. Their expedition to the Gothic king Ermanaric to exact vengeance is doomed. Just before his death at the hands of the Goths in Guðrúnarhvöt 30, Gudrún’s son Sörli remarks “none outlives the night when the norns have spoken” (kveld lifir maðr ekki eftir kvið norna). The same sentiment is expressed in Fjölsvinnsmál 47:

|

Urðar orði |

No one can oppose, Urd's decree, even though it incurs blame. |

Even suicide is futile for one so fated. In Guðrúnarhvöt 13, Guðrún’s attempt to drown herself in order to escape the Norns’ wrath fails. She throws herself in the sea, but “the billows bear her undrowned.” The Norns alone determine the span of everyone's life.

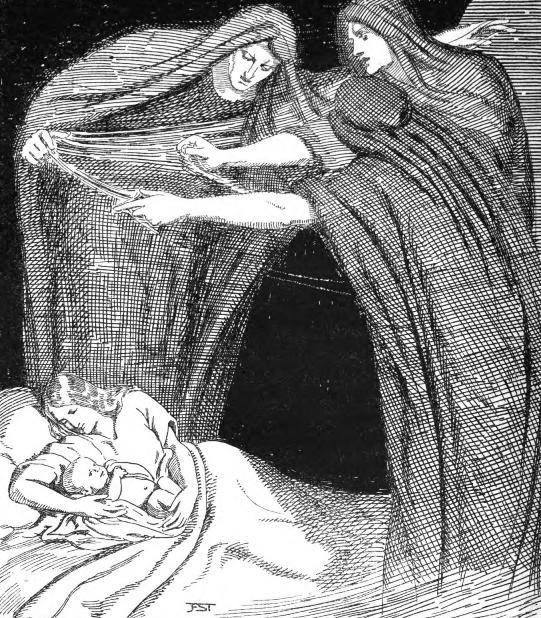

The Norns, an illustration from a book by Amalia Schoppe, 1832

Besides this important function, the Norns also tend Yggdrasil’s Ash, laving it with the holy waters from Urd’s well. Elaborating on a passage in Völuspá 19 (which he quotes), Snorri explains:

|

Enn er þat sagt, at nornir þær, er byggja við Urðarbrunn,

taka hvern dag vatn í brunninum ok með aurinn þann, er liggr um

brunninn, ok ausa upp yfir askinn, til þess at eigi skuli limar

hans tréna eða fúna. En þat vatn er svá heilagt, at allir

hlutir, þeir er þar koma í brunninn, verða svá hvítir sem hinna

sú, er skjall heitir, er innan liggr við eggskurn, svá sem hér

segir: |

It is further said that these Norns who dwell by the Well of Urdr take water of the well every day, and with it that clay which lies about the well, and sprinkle it over the Ash, to the end that its limbs shall not wither nor rot; for that water is so holy that all things which come there into the well become as white as the film which lies within the egg-shell,--as is here said: |

|

Ask veit ek ausinn, |

I know an Ash standing

|

The poem

Fjölsvinnsmál gives us additional insights

into the nature of the world-tree. There the young hero Svipdag approaches the

gates of Asgard, asking Fjölviður (Odin, cp. Grímnismál 47) about what he sees

there:

|

19. |

Now tell me, Fjolsvith, what I will ask you |

|

|

20. Mimameidur is its name, and few are they who know from what roots it grows; by what it will fall, few know; neither fire nor iron can fell it. |

Stanza 22 informs us about the special qualities of its fruit:

|

Út af hans aldni |

Its fruit is taken |

Of interest here, in the last stanza, the tree is said to “mete out fate among men”

(mönnum mjötuður). The word mjötuður is related to Old

English Metod (a name of the Christian God in Beowulf)

and its meaning is undisputed:

"one who metes out, force of destiny, fate". The World-Tree is actually

named mjötviður, ‘the tree of fate”, in

Völuspá 2.

Although stanza 22 is cryptic, it seems to suggest that the fruits of

this tree were seen as forming the embryos of human beings, the seed of

life. They are transported into the wombs of women, and there

transformed into human embryos upon a creative "fire" burning inside the

belly. The womb carries the unborn child (innar skýli) until the time

comes for it to be born (utar hverfa). In light of such an

interpretation, it becomes obvious why the tree “metes out fate among

men.” Human beings are literally born from it, grown upon its branches

as fruit. As weavers of fate, the norns were probably thought to oversee

this process.

The notion of apples becoming embryos has been preserved in Chapter 2 of Völsungasaga. Unable to have a child, King Rerir and his pray to the gods for a child. Frigg hears their prayer and gives one of Odin's valkyries an apple to bring it to the king. In the guise of a crow, she drops the apple into the king's lap, while he is sitting atop a grave-mound. After eating of the apple, his wife becomes pregnant.

In confirmation of this, Mimameidur means “Mimir’s Tree.” There can be little doubt that Mimameidur is Yggdrasill, the World-Tree, itself. This identification is supported by the use of a similar formulation in Hávamál 138 to describe a vindga meiði, “windy tree” that Odin hung himself on:

|

Veit ek, at ek hekk |

I know that I

hung on that windy tree, nine full nights, Given to Odin, me to myself, From what roots it grows |

According to the present interpretation of the ancient Germanic world-view (see Grímnismál 29, 30 and 31), all three roots of the World-Tree are located in the underworld: one in the spring Hvergelmir, one in Mimir's well, and one in Urd's well. At the apex of the tree, we find Asgard, the home of the gods. From Grímnismál 25-26, we learn that the goat Heiðrún and the hart Eikþyrnir stand on the roof of Odin's residence, Valhöll, grazing on the foliage of the tree. This suggests that Valhöll was situated at the center of the divine city, and was built around the tree's bole, which therefore must have penetrated the roof of the palace. The topmost part of the tree is thus seen as forming a leafy canopy over the home of the gods. We find evidence of this in the description of Völsung's palace in Völsunga saga, Chapter 2, where a great oak grows inside the palace, penetrating its roof, and the tree's verdant foliage adorned with beautiful blooms, spreads out over it (eik ein mikil stóð inni í höllinni, ok limar trésins með fögrum blómum stóðu út um ræfr hallarinnar, en leggurinn stóð niðr í höllina). Both Völuspa and Fjölsvinnsmál inform us that a golden roster perches in the uppermost branches. Völuspa calls him Gullinkambi (Gold-comb). The later poem describes him this way:

|

23/4-6: Hvað sá hani heitir |

What is the name of the cock who sits in the lofty tree, all aglow with gold? |

|

24/1-3: Víðófnir hann heitir,

|

His name is Vidofnir, and he stands upon Vedurglasir, the boughs of Mími's tree; |

From the context, Veðurglasir (“Weather-Glasir”) appears to be another designation for Mimir’s tree. Here it is used as a proper name. To properly understand its meaning, the word must be considered in the context of the poem. In verse 28, we are introduced to a parallel term, Aurglasir (“Mud-Glasir”).

|

Aftur mun koma, |

He who seeks the sword and desires to possess it, shall return, only if he brings a rare object to ‘Eir of Aurglasir’. |

"Why is gold called Glasir's foliage or leaves? In Asgard, in front of the doors of Valhöll, there stands a tree called Glasir, and all its foliage is red gold, as in this verse where it says that:

'Glasir stands

with golden leaves

before Odin's halls'.

"This tree is the most splendid one among gods and men."

"This name (Veðurglasir) seems to be a name of that part of Mímameiður, which rises above the earth, and is afflicted by the weather and the winds."

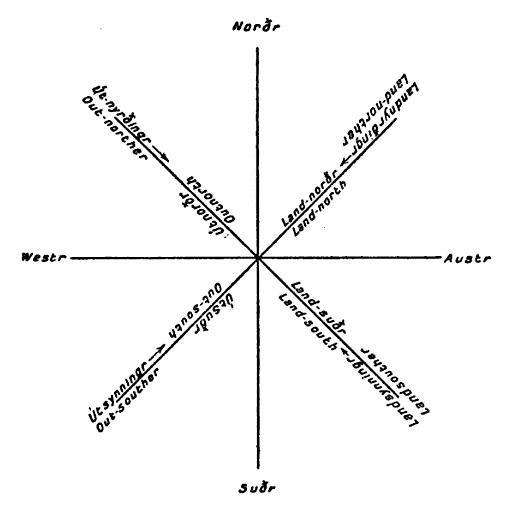

Thus the name Veðurglasir is a synonym of the term vindga meiði, “windy tree” (Hávamál 138). Such an interpretation might also explain the name Yggdrasill, "Odin's horse". Of course, Odin’s horse is the eight-legged Sleipnir. As the central point of the universe, the World-Tree was at the center of the eight directions, also known as the eight winds. Odin is its rider. As the great traveler of the lore, Odin was thus seen as riding the eight winds, symbolized as an eight-legged horse. (See Eiríkr Magnússon, Odin's Horse Yggdrasill, 1895, pp. 47 ff).

The Eight Winds |

||

Aurglasir is obviously another name for the World-Tree. In stanza 24 Veðurglasir was used as a name of that part of the Tree visible above-ground, the part exposed to the winds. Aurglasir is its opposite. Aur means "mud, soil, clay", thus Aurglasir must be the portion of Yggdrassil hidden below-ground, the lower half of the Tree.

All the occurrences of the word “aur” in the Eddic poems can be explained by the meaning "mud, wet clay, wet soil, loam". It signifies the richness of muddy soil as a source of growth and fertility. The primeval giant Ymir was known as Aurgelmir among the giants (Vafþrúðnismál 29, cp. Gylfaginning 5). The soil of the earth was made from his flesh, and was fertile because he sucked the milk of the primeval cow Audhumla. In Völuspá 19 we also find aur- intimately connected with the World-Tree. Here the tree is ausinn hvíta auri, “drenched with white mud.” Aur- is more accurately understood as "muddy water, water blended with mud", an interpretation supported by Snorri's account in Gylfaginning 16.

This mythological aur- was obviously no ordinary

brown mud, but a mud of pristine, white purity, which seems to have

suffused the World-Tree with life. The source of this hvíta auri,

snow-white clay, appears to be Urd’s well, as “these Norns who dwell by

the Well of Urd take water of the well every day, and with it that clay

which lies about the well, and sprinkle it over the Ash, to the end that

its limbs shall not wither nor rot” (at nornir þær, er byggja við

Urðarbrunn, taka hvern dag vatn í brunninum ok með aurinn þann, er liggr

um brunninn, ok ausa upp yfir askinn, til þess at eigi skuli limar hans

tréna eða fúna.) Everything it comes in contact with turns as white as

the inner lining of an eggshell. In confirmation of this, Gylfaginning

16 further informs us that snow-white birds swim in its waters:

“Two fowls are fed in Urd's Well: they are called Swans, and from those fowls has come the race of birds which is so called."

We cannot be sure why Snorri chose the term skjall (the membrane of an egg) to clarify the image, but it should be noted that this membrane is semi-transparent. The same word was used of a translucent membrane, stretched over a frame, and used as a window (instead of glass). Snorri may have meant to imply that the Tree itself is transparent, effectively explaining why, even though it spreads over all lands, it remains invisible to the naked eye. According to medieval legend, shooting stars foretold the birth of a child. As the fruit of the world-tree, unborn souls that occasionally fell to earth as meteors (shooting stars). This opens the very real possibility that the stars were seen as the golden apples growing in the uppermost branches of the tree, visible as the twinkling stars at night. Glittering as it was, the uppermost part of the World-Tree was probably considered to be the most beautiful and precious part of the tree

|

Veit hon Heimdallar |

She knows that Heimdall’s hearing (his ear?) is hidden Under that 'brilliant' holy tree She sees a river surge with muddy stream From Val-father’s pledge, do ye know yet, or what? |

“heid-vanr: accustomed to brightness, Völuspá 27” from “heiðr, adj. bright, clear— used of days, the sky, the sun and the stars.”

“heiðvönum: probably a play on two sense of heið, ‘shining mead’ and ‘shining heaven,’ the tree’s roots being in the mead, its branches on the heavens."

In Fjölsvinnsmál 28, the phrase ‘Eir Aurglasis’ is best understood as a kenning for the pale giantess Sinmara (named in sts. 24, 26, and 30). Eir is the goddess of healing, the physician of the gods, according to Gylfaginning 35. As such, her name was frequently used as a base in synonyms for women in skaldic kennings. Sinmara is thus the woman, or perhaps even the 'healer' or 'physician' of Aurglasir. Since Urd and her sisters lave the tree with mud from her well, keeping the World-Tree healthy, Sinmara appears to be another name for Urd.

On the Norns' Seats:

The Judgment of the Dead

In the Norse sources, death is often spoken of as norna dómr, norna sköp, or norna kviðr —“the judgment of the Norns.” As shown above, their doom is inescapable. Because Snorri does not mention one, many have assumed that the Norse religion lacked a judgement seat for the dead. Yet, a careful examination of the sources reveals just such a process.

For example,

describing mál-runar (speech-runes), the Eddaic poem Sigurdrífumál 12

says:

|

12. Málrúnar

skaltu kunna ef þú vilt, at

manngi þér heiftum gjaldi

harm: þær of vindr, þær of vefr, þær of setr

allar saman, á því þingi, er þjóðir

skulu í fulla dóma

fara. |

12.

Mál-(speech-) runes you must know, if you would

that no one requite you

for injury with hate. Those you must

wind, those you must

wrap round, those you must

altogether place in that court

(Thing), where people

have to go into

full judgment.

|

|

77. Deyr fé deyja frændur, deyr sjálfur

ið sama. Eg veit einn að aldrei

deyr: dómur um

dauðan hvern. |

"Your cattle

shall die; your kindred

shall die; you yourself

shall die; one thing I

know which never

dies: the judgment

on each one dead." |

This stanza, in conjuction with Hávamál 76, is typically interpreted to mean that the fame one wins while alive is undying. A bit of reflection by a person with a few years under their belt reveals that is not the case. We know that the deeds of most of those who lived two or three generations before us are wholley forgotten. Yet, stanza 77 says that the judgment on "each one dead" never dies, not just the famous. Clearly, something else is meant.

Where and how this

judgment occurs is of great importance to determining the heathen belief

regarding the dead. Thankfully, the Eddaic poems also contain clues that

illuminate the process.

Fáfnismál 10 informs

us:

|

77. því at einu

sinni

hverr |

“For there is

a time when every man shall journey

hence to Hel." |

Since "every man" must fare to Hel, even those chosen for Valhöll are no exemption. In several sources, we find examples of warriors killed in the line of duty who are said to come “to Hel”. Thus, like all men, warriors too first travel “to Hel” before ascending to Valhöll. Hel is its antechamber. Gisli Surson's Saga (ch. 24) confirms this, when it says that it is custom to bind Hel-shoes on the feet of the dead; even those of whom there was no doubt that Valhöll was their final destiny received Hel-shoes like the rest, það er tíðska að binda mönnum helskó, sem menn skulu á ganga til Valhallar, ("It is custom to bind hel-shoes to men, so that they shall walk on to Valhöll"). Since the youngest Norn, Skuld, is also the foremost of the valkyries (cp. Völuspá 20, 30), we see that Urd and her sisters indeed have some role to play in the process. Similarly, in Gylfaginning 50, five fylki ('military troops') accompany Baldur to the underworld.

In the poem

Sólarljóð, after traveling the road to Hel, the deceased poet informs us

that after entering the Hel-gates, dead men must sit on “Norns’ seats”

for nine days. What they wait for is not stated.

|

51. Á norna

stóli Sat ek níu

daga, þaðan var ek á

hest hafinn, gýgjar sólir skinu

grimmliga ór skýdrúpnis

skýjum. |

51. In the

Norns' seat nine day I

sat, thence I was

mounted on a horse: there the

giantess's sun shone grimly through the

dripping clouds of heaven.

|

In Sólarljóð 44, he informs us that his

tongue “became like wood,”

(tunga

mín var til trés metin), making it impossible to speak.

Hávamál 111

describes a similar scene:

|

112. Mál er að

þylja þular stóli á Urðarbrunni

að. Sá eg og

þagða'g, sá eg og

hugða'g, hlydda eg á

manna mál. |

112. ‘Tis time

to speak from the

sage’s chair. - By the well of

Urd I sat

silently, I saw and

meditated, I listened to

men’s words. |

|

113. Of rúnar

heyrða eg dæma, né um ráðum

þögðu Háva höllu að, Háva höllu í, heyrða eg

segja svá: |

113. Of runes

I heard discourse, nor of sage

counsels were they silent, at the High

One’s hall. In the High

One’s hall Thus I heard

them speak. |

This is consistent with several heathen accounts, where runes are required to loosen the tongue of a dead man allowing him the power of speech. In Hávamál 157, Odin employs speech-runes when he carves í rúnum, so that a corpse from the gallows comes down and mælir (speaks) with him. According to Saxo (Book 1), Hadding’s companion Hardgrep places a piece of wood carved with runes under the tongue of a dead man. The corpse recovers consciousness and the power of speech, and sings a terrible song, cursing her for it. In Guðrúnarkviða in fyrsta, it is told how Gudrun, mute and almost lifeless (gerðist að deyja), sat near Sigurd's dead body. One of the kinswomen present lifts the veil from Sigurd's head. At the sight of her loved one, Gudrun awakens, bursts into tears, and is able to speak. Brynhild then curses the being (vættur) which "gave speech-runes to Gudrun" (st. 23), that is to say, freed her tongue, until then sealed as in death. Thus it follows that the dead pass silently into Hel. We have additional confirmation of this in Gyfaginning 50, when Hermod rides to Hel on Sleipnir, seeking Baldur. Madgud, the watch at the golden bridge over Gjöll says he alone makes more noise that five fylki, "military troops," who preceded him the day before.

In Hávamál 112-113, the speaker “sits silently” meditating by Urd’s well, listening to discourse, just as in Sólarljóð, where the dead man sits with wooden tongue “on the Norns’ seats.” Since this is the place speech-runes are most useful, it must be the court where men go into “full judgment” (Sigurdrífumál 12).

Without drawing any

conclusions, let’s restate what we have learned according to these

heathen sources:

1. All men eventually come to Hel, even warriors whose final destination is Valhöll (Fafnismál 10, Gisli Súrsson's Saga, ch. 24, etc). |

Based on this, it is reasonable to conclude that in the genuine heathen conception, the dead first gather in Hel by Urd’s well, and more specifically at a court found there, awaiting judgment, their final fate not yet determined. From a wide variety of sources, we know that those who die on the battlefield will eventually pass over Bifröst to Valhöll (located in the celestial city of Asgard), while “wicked” people will “die” again and be sent northward to Niflhel (Vafþrúðnismál 44). Presumably, the rest will remain in Hel, the warm green fields surrounding Urd’s thingstead, to dwell with their families. These, Völuspá speaks of "those on the hel-ways". Saxo (Book 1) tells us this realm is sunny and fertile.

At this juncture, the

destination of the dead is not certain, apparently even for those killed

on the battlefield. In Njáls Saga, ch. 88, of the heathen Hrapp, who had

burnt a heathen temple and stripped the idols of their riches, Hakon

says: "The gods are in no haste to seek vengeance, the man who did this

shall be driven out of Valhöll forever," (Magnus Magnusson and Hermann

Pálsson translation)

If the purpose of the

journey to Hel is to appear at the court by Urd’s well and wait for

judgment and even warriors chosen for Valhöll must stop here before

passing over Bifröst to Asgard and Valhöll, we might suspect that the

gods have some involvement in the matter, since ultimately it is Odin

and Freyja who decides who enters their halls, Valhöll and Sessrumnir.

Hávamál 113 equates this court with the "High One's", Odin's hall, while

Grímnismál 14 states:

|

14. Fólkvangr

er inn níundi, en þar Freyja

ræðr sessa kostum í

sal; hálfan val hún

kýss hverjan dag, en hálfan

Óðinn á. |

14. “Folkvang

is the ninth, there Freyja

directs the sittings

in the hall. She chooses

half the fallen each day, but Odin the

other half.” |

Since the gods are in

no hurry to seek vengeance against those who desecrate their shrines,

this suggests they expect there will be a time for certain redress in

the future. Such a view might give comfort to the faithful heathen who

saw such men prosper in life, seemingly unpunished for their

violations of heathen moral laws.

They could take solace in their knowledge that the gods would act

in the due course of time, if not in this lifetime, then the next.

While other Eddaic

poems speak of a judgment on each one dead, place dead men “on

Norn’s seats,” and speak of a court at Urd’s well, the Eddaic poem

Grímnismál, stanzas 29 and 30, inform us that the gods ride over Bifröst

“every day” to sit in judgment by Urd’s well.

Your Own Personal Hel |

||||

|

Although the Eddic poems most frequently speak of Hel as a place,

Grímnismál 31's expression regarding the root as being

"with Hel" implies a personal being. Skaldic passages found in

Heimskringla also make it clear that the ancient religion knew of a

female being by this name. From the investigations above, it

is clear that the name Hel, when used of an individual entity, must

refer to Urd, as the goddess of fate and death.

Yet, in Snorri's Edda (Gylfaginning 36), we find the name attributed

to one of Loki's children:

|

||||

|

INTERLUDE: "Permit me to

present a brief sketch of how the cosmography and eschatology of

Gylfaginning developed from the assumption that the Aesir were

originally men, and dwelt in the city of Troy which was situated on the

center of the earth, and which was identical with Asgard (Gylfaginning

9). (—Undersökningar i Germanisk Mytologi, no. 67) |

||||

| The tale of Hermod's Hel-Ride is found in Gylfaginning 50. Here, as in the poem Baldur's Dreams, the palace of Hel has a much different feel. In the poem Baldur's Dreams, st. 2 and 3, Odin rides through Niflhel, and upon crossing into Hel, where he is met by a dog, bloody about the breast, he sees Heljar rann, "Hel's high hall." As described in stanza 6, the benches are draped with ring-mail and the costly couches are decked with gold. In stanza 7, golden goblets, covered by shields, stand filled with 'clear mead' awaiting Baldur's arrival. In Gylfaginning 50, Baldur and Nanna are allowed to receive a visitor and send him off with costly objects of gold and linen as gifts for Odin and Frigg. | ||||

|

||||

| Christopher Abram, in 'Snorri's

Invention of Hermóðr's helreið', 13th International Saga

Conference, 2006 remarks that "many scholars have accepted the existence

of a lost poetic archetype of this myth." The evidence for this is

"primarily stylistic, and focuses on alliteration in Snorri's prose."

The inclusion of a stanza, found nowhere else, may also indicate a

poetic source lurking in the background. However, that aside, "outside

of Snorri's account, there is no extant version of this or any other

myth that features a personification of pagan Hel," Abrahm concludes

that "it is sufficient to recognize that a personification of the

underworld is an important character in Christian descent narratives

that are typologically cognate with Hermóðr's helreið." In Gylfaginning 36, Snorri says, Odin give Loki's daughter power over all who come to her realm, men dead of sickness or of old age. He casts her into Niflheim. Baldur and Hödur, however, both were killed with weapons, and come to Hel. As we have seen, Hel and Niflhel are distinct realms in the eddic poems. Nor does Loki's daughter have the power to grant life, once it has been taken. That power is reserved exclusively for Urd (the real Hel). Loki's daughter is most likely one of Urd's maid-servants. Since the beings for whom Urd determines birth, position in life, and death, are countless, so too her servants, who perform the tasks commanded by her as queen, must also be innumerable. They belong to two classes: the one class is active in her service in regard to life, the other in regard to death. Most intimately associated with her are her two sisters, Verdandi and Skuld. With her they have authority as judges. They dwell with her under the world-tree, (Völuspá 20). As

maid-servants under Urd, there are also countless

hamingjur

and fylgjur. The hamingjur are

fostered among beings of giant-race

(Vafþrúðnismál

48, 49). There every child of man is to have a

hamingja as a companion and

guardian spirit. The testimony of the Icelandic sagas of the Middle Ages

are confirmed in this regard by phrases and forms of speech which have

their root in heathendom. The

hamingjur belong to that large circle of feminine beings which are

called dises (dísir).

What Urd is on a grand scale as the guardian of the mighty Yggdrasil,

the hamingja is on a smaller

scale when she protects the separate fruit produced on the world-tree

and placed in her care. She does not appear to her favorite excepting

perhaps in dreams or shortly before his death (the latter according to

Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar, the

prose at 35; Njal's saga, 62;

Hallfreðar Saga

Vandræðskálds ch. 11, etc) That the

hamingjur were noble beings

was a belief preserved through the Christian centuries in Another

division of this class of maid-servants under Urd are those who attend

the entrance of a child into the world, and who weave the threads of the

new-born babe's life into the web of its family. Like Urd and her

sisters, they too are called norns. If the child is to be a great and

famous man, Urd herself may be present.

Fáfnismál 12-13 speak of norns

whose task it is to determine and assist the arrival of the child into

this world. They are said "to choose mothers from descendants," to

select a seed from the indefinate crowd of eventual descendants, who at

the threshold of life are waiting for mothers to become born into this

world. These norns are, according to

Fáfnismál 13, of different

birth. Some are Asynjes, others of elf-race, and again others are

daughters of Dvalin.

To the other

class of Urd's maid-servants belong those beings which execute her

death-decrees and conduct the souls of the departed to the lower world.

Since all the dead, whether they are destined for Valhöll, for Hel (the realms of bliss), or for Niflhel, must first report to Urd's thingstead in Hel, their psychopomps, whether they dwell in Valhöll, Hel, or Niflhel, must do likewise. This arrangement is necessary so that the damned who, a second time, "die from Hel into Niflhel" (Vafþrúðnismál 44) must have attendants to conduct them from the realms of bliss to the Nagrindr ('Corpse-gates) and into the realms of torture. Those dead from disease, who have the kinswoman of Loki as a guide, may be destined for the realms of bliss. If so, she delivers them there and departs for her hom ein Niflhel; or if her charge is destined for Niflhel -- then they die under her care and are brought by her through the Nagrindr to the places of torture in Niflhel (Völuspá 36-38). So if Loki's daughter is not the personal Hel, what is her name? It may still be possible to recover it from the fragmentary sources, although not with any degree of certianty. In our mythical records there is mention made of a giantess whose name, Leikn, is immediately connected with the power which Loki's kinswoman exercises when she appears to a dying person. In its strophe about King Dyggvi, who died from disease, Ynglingatal says (Ynglingingasaga 17) that, as the lower world dis had chosen him, Loki's kinswoman came and made him leikinn (alvald Yngva þjóðar Loka mær um leikinn hefir). She deludes (leikinn) him, bringing on mental or physical disease. Of this personal Leikn, we get the following information in our ancient records: 1. Like Loki, she is of giant race (Prose Edda, Nafnaþulur 15). 2. She has once fared badly at Thor's hands. He broke her legs (Leggi brauzt þú Leiknar - Skáldskaparmál 11, after a song by Veturliði). 3. She is kveldriða, an "evening-rider, a nighthag, a witch." Akin to kvelja (to torment). 4. The horse which this giantess rides is black, untamed, difficult to manage (styggr), and ugly-grown (ljótvaxinn). It drinks human blood, and is accompanied by other horses, black and bloodthirsty like it. (Hallfreður Vandræðaskáld in Heimskringla, Ólafs saga Tryggv., ch. 29.) Popular traditions have preserved the remembrance of a three-legged horse, which on its appearance brings sickness, epidemics, and plagues. According to popular belief in Schleswig (Arnkiel, I. 55; cp. J. Grimm, Deutsche Myth., Vol. II, Ch. 27), Hel rides on a three-legged horse during the time of plague and kills people. Grimm, DM Vol. II, Ch. 27 says "In Denmark, one who blunders about clumsily is said to 'gaaer som en helhest,' go about like a hel-horse. According to folklore, this hel-horse walks around the churchyard on three legs, fetching the dead." Theile, 137: A custom is mentioned in which a live horse is buried in a churchyard before the first human body is buried, so that it may become the walking dead horse. Theile, 138: One who has survived a serious illness will say "Jeg gav Döden en skiäppe havre," I gave Death a bushel of oats (for his horse). Ankeil quotes I, 55, that according to superstition in times of plague "the Hell rides about on a three-legged horse destroying men," and when the plague is over it is said "Hell is driven away." Thus the ugly-grown horse is not forgotten in traditions from the heathen time. While there is no doubt that the Loki-daughter is a distinct personality separate from Hel-Urd, evidence for her actual name is weak. The most compelling evidence for this conclusion is the statement that Thor broke Leikn's legs, and the statement that Odin cast her into Niflheim, Hel kastaði hann í Niflheim. (For a similar statement in regard to Thjazi's eyes cp. Skáldskaparmál 4, and Harbardsljóð 19). For want of a better name, I can accept Leikn as a name of Loki's daughter, but each reader must decide how valid this conclusion is. |

||||

|

|

||||

For additional insights into Urd and her character

see verses 2, 9, 11, 12, 15, 20, and 21 of

Hrafnagaldur Óðinns

[PREVIOUS][GRIMNISMAL 31][NEXT]

[MAIN][HOME]