The Poetic Edda: A Study Guide

The Speech of the Masked One

[PREVIOUS][MAIN][NEXT]

[HOME]

MS No. 2365 4to [R]

AM 748 I 4to [A]

Normalized Text:

33. Hirtir eru ok fjórir,

þeirs af hefingar á

agaghalSir gnaga:

Dáinn ok Dvalinn,

Dvneyr ok Dvraþrór.

þeirs af hæfingiar á

gaghalsir gnaga:

Dáinn ok Dvalinn,

Dýneyr ok Dyraþrór.

33. Hirtir eru ok fjórir,

þeirs af hæfingar

gaghálsir gnaga:

Dáinn ok Dvalinn,

Duneyrr ok Duraþrór.

in Icelandic Poetry

“The Song of Grimnir”

The Yale Magazine, Vol. 16

“The Song of Grimner”

Four Stags[2] protected by its boughs,

With lifted foreheads daily browze.

[2] “Four Stags," --- Their names are, Dainn, Dualinn, Duneyrr, and Duradror.

Dainn, Dualin,

Duneyrr,'and Durathror—

Who, twisting their necks,

gnaw the boughs of the ash.

in Edda Sæmundar Hinns Frôða

“The Lay of Grimnir”

in Corpus Poeticum Boreale

“The Sayings of the Hooded One”

33. Harts there are also four,

which from its summits,

arch-necked, gnaw.

Dain and Dvalin,

Duneyr and Durathror.

There are four bow-necked Harts that gnaw the [high shoots]: Dain and Dwalin, Duneyr and Durathror.

in Edda Saemundar

“The Sayings of Grimnir”

in The Poetic Edda

“Grimnismol: The Ballad of Grimnir”

gnaw the topmost boughs of the tree :

Dainn the Dead One. Dvalin the Dallier,

Duneyr and Dyrathror.

that the [2] highest twigs

Nibble with necks bent back;

Dain and Dvalin, -lacuna-

Duneyr and Dyrathror.

[1] Stanzas 33-34 may well be interpolated and are certainly in bad shape in the manuscripts. Bugge points out that they are probably of later origin than those surrounding them.

[2] Highest twigs: a guess. The manuscripts' words are baffling. Something apparently has been lost between lines 3-4.

in The Poetic Edda

“The Lay of Grimnir”

in The Elder Edda

“The Lay of Grimnir”

34. [1][Four

harts also the highest shoots[2]

ay gnaw from beneath:

Dáin and Dvalin,[3]

Duneyr and Dyrathror.]

[1]

The following two stanzas are very likely interpolations.

[2] Conjecturally.

[3] These are, rather,

dwarf names.

33. Four the harts who the high boughs

Gnaw with necks thrown back:

Dain and Dvalin,

Duneyr and Durathror.

in The Poetic Edda

“Grimnir’s Sayings”

in The Poetic Edda, Vol. III: Mythological Poems

“The Lay of Grimnir”

33. 'There are four harts too, who gnaw with necks thrown

back

the highest boughs;

Dain and Dvalin,

Duneyr and Durathror.

33. There are also four stags who

from [their proper sweet pasture]

[perpetually] nibble with straining neck:

Dead One and Dawdling One,

Downy Beach and Door Stubborn.

The Elder Edda: A Book of Viking Lore

'The Lay of Grimnir"

they gnaw with necks thrown-back:

Dead-one and Dawdler,

Duneyr and Durathrór.

[HOME][GRÍMNISMÁL]

en fjórir hirtir renna í limum asksins ok bíta barr. Þeir heita svá: Dáinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr, Duraþrór. En svá margir ormar eru í Hvergelmi með Níðhögg, at engi tunga má telja. |

XVI. ...and four harts run in the limbs of the Ash and bite the leaves. They are called thus: Dáinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr, Durathrór. |

Of the four animals named here, only the first two can be translated with certianty. The last two names, Duneyrr ok Duraþrór, are of uncertain meaning. They have been translated variously as:

'Murmur' and 'Delay'; "The Symbolism of the Eddas", National Review Quarterly, 1865.

'Quiets-Noise' (Apaise-Bruit) and 'Drowsy' (Somnolent); Frederic Bergmann, Dits de Grimir, 1871

'The noisy, maker of din' and 'the door-breaker(?)'; Benjamin Thorpe, Northern Mythology, 1851

'Downy Beach' and 'Door Stubborn'; Ursula Dronke, Poetic Edda III, 2011

The names of the first and second hart, however, can be established. Dáinn means "the dead one", and is derived from the verb deyja, 'dead, deceased', (cp. Danish daane = 'to swoon') according to the Cleasby-Vigfusson Dictionary. Dáinn has been variously translated as:

'Swoon'; National Review Quarterly, 1865.

'Swooning'; Benjamin Thorpe, Northern Mythology, 1851

'Made-drowsy' (Assoupi); Frederic Bergmann, Dits de Grimir, 1871

'Dead one" Olive Bray, The Elder or Poetic Edda, 1908

'Dead-one'; Andy Orchard, The Elder Edda, 2011

'Dead One'; Ursula Dronke, Poetic Edda III, 2011

Dvalinn can be interpreted as "one who dallies", (Cleasby/Vigfusson, Dictionary) or as "one who lies in slumber" (Egilsson, Lexicon Poeticum), derived from dvala, 'to slow down' or dvelja, 'to delay.' The name has been variously translated as:

'Sleep'; National Review Quarterly, 1865.

'Torpid'; Benjamin Thorpe, Northern Mythology, 1851

'Fainting" (Défaillant); Frederic Bergmann, Dits de Grimir, 1871

'Dallier'; Olive Bray, The Elder or Poetic Edda, 1908

'Dawdling One'; Ursula Dronke, Poetic Edda III, 2011

'Dawdler'; Andy Orchard, The Elder Edda, 2011

Based on the meaning of their names, Dáinn and Dvalinn, may be the Germanic representatives of Death and Sleep. Notably, the names Dáinn and Dvalinn, are most often applied to dwarves found throughout the lore. Other than here in Grímnismál 33 and in a list of hart names in Skáldskaparmál, Dáinn and Dvalinn are named together as dwarves in Völuspá 11 and Hávamál 143.

Dáinn appears in Hyndluljóð 7 and Hrafnagaldur Óðinns 3.

Dvalinn is named in Völuspá 14, Alvismál 16, Fafnismál 13, in a verse by Ormr Steinþórsson in Skáldskaparmál 10, a list of kennings in Skáldskaparmál 56, and as owner of the horse Móðnir in a fragment of the poem Alvinnsmál preserved in Skáldskaparmál 58. In the late Fornaldarsaga titled, Hervarar saga og Heiðreks, the dwarf Dvalin makes the sword Tyrfing. In Sörla Þáttur eða Héðins Saga ok Högna, the four dwarves who forge Freyja's necklace Brisingamen are named Álfrigg, Dvalinn, Berlingr, and Grérr. In Sólarljóð 78, we find the name Vig-Dvalin, in a poetic reference to a tale told of the dwarf Álfrigg in Þiðreks Saga af Bern ch. 40.

Thus, if the harts are symbolic, it seems most likely that they represent dwarves.

Dvergr: Dwarves in Germanic Lore

The author of the dwarf-list in Völuspá 11-16 makes all holy

powers assemble to consult as to who shall create "the dwarves," the

artist-clan of the mythology. The wording of

strophe 10 indicates that on a

being by name Móðsognir, Mótsognir, was bestowed the dignity of chief of the

proposed artist-clan [þar var Móðsognir mæztr um orðinn dverga allra] and

that he, with the assistance of Durin (Durinn), carried out the resolution

of the gods, and created dwarves resembling men. The author of the dwarf

list must have assumed -

That Modsognir was one of the older beings of the world, for the assembly of

gods here in question took place in the morning of time before the creation

was completed.

That Modsognir possessed a promethean power of creating.

That he either belonged to the circle of holy powers himself, or stood in a

close and friendly relation to them, since he carried out the resolve of the

gods.

Accordingly, we should take Modsognir to be one of the more remarkable

characters of the mythology. But either he is not mentioned anywhere else

than in this place - we look in vain for the name Modsognir elsewhere - or

this name is merely a skaldic epithet, which has taken the place of a more

common name, and which by reference to a familiar distinguishing

characteristic indicates a mythic person well known and mentioned elsewhere.

It cannot be disputed that the word looks like an epithet. Egilsson (Lexicon

Poeticum) defines it as the mead-drinker (‘one who sucks in mead’). If the

definition is correct, then the epithet was badly chosen if it did not refer

to Mimir, who originally was the sole possessor of the mythic mead, and who

daily drank of it (Völuspá 28 - drekkur mjöð Mímir morgun hverjan).

Still nothing can be built simply on the definition of a name, even if it is

correct beyond a doubt. All the indices which are calculated to shed light

on a question should be collected and examined. Only when they all point in

the same direction, and give evidence in favor of one and the same solution

of the problem, the latter can be regarded as settled.

Zuo siner (Mimir's)

meisterschefte

Several of the "dwarves" created by Modsognir are named in Völuspá 11-13.

Among them is Dvalin. In the opinion of the author of the list of dwarves,

Dvalin must have occupied a conspicuous place among them, for he is the only

one of all the dwarves who is mentioned as having a number of his own kind

as subjects (Völuspá 14 - dverga í Dvalins liði, “the dwarves in

Dvalin’s band”). Therefore, the problem as to whether Modsognir is identical

with Mimir should be decided by the answers to the following questions:

Is that which is said about Modsognir also said of Mimir?

Do the statements which we have about Dvalin show that he was particularly

connected with Mimir and with the lower world, the realm of Mimir?

Of Modsognir, it is said (Völuspá 10) that he

was mæztr um orðinn dverga allra: he became the chief of all dwarves, or, in

other words, the foremost among all artists. Have we any similar report of

Mimir?

The German middle-age poem, "Biterolf," relates that its hero possessed a

sword, made by Mimir the Old, Mime der alte, who was the most excellent

smith in the world. Even Wieland (Völund, Wayland was not to be

compared with him), still less anyone else, with the one exception of

Hertrich, who was Mimir's co-laborer, and assisted him in making all the

treasures he produced (Biterolf, 144 ff.):

ich nieman kan gelichen

in allen fürsten richen

an einen, den ich nenne,

daz man in dar bi erkenne:

Der war Hertrich genant.

. . . . . . .

Durch ir sinne craft

so hæten sie geselleschaft

an werke und an allen dingen. To his (Mimir's) mastery

I can compare no one

in all the princely realms

except the one that I name,

so that he is recognized thereby:

He was named Hertrich.

. . . . . . .

Through the power of their understanding

they were able to collaborate

on works and on all things

Þidreks Saga af Bern, which is based on both German and Norse sources,

states that Mimir was an artist, in whose workshop the sons of princes and

the most famous smiths learned the trade of the smith. Among his apprentices

are mentioned Velint (Völund), Sigurd-Sven, and Eckehard.

It should be remembered what Saxo also tells of incomparable treasures which

are preserved in Gudmund-Mimir's domain, among which are arma humanorum

corporum habitu grandiora, “arms laid out too great for those of human

stature” (Hist., Book 8) and about the satyr Mimingus (‘son of Mimir’), who

possesses the sword of victory, and an arm-ring which produces wealth

(Hist., Book 3). If we consult the poetic Edda, we find Mimir mentioned as

Hodd-Mimir, Treasure-Mimir (Vafþrúðnismál 45); as naddgöfugr jötunn, the

giant celebrated for his weapons (Gróugaldur 14); as Hoddrofnir, or

Hodd-dropnir, the treasure-dropping one (Sigurdrífumál 13); as Baugreginn,

the king of the gold-rings (Sólarljóð 56). And as shall be shown hereafter,

the chief smiths in the poetic Edda are put in connection with Mimir as the

one on whose fields they dwell, or in whose smithy they work.

In the Norse sagas of the Middle Ages, the dwarf Dvalin, created by

Modsognir, is remembered as an extraordinary artist. There he is said to

have assisted in the fashioning of the sword Tyrfing (Hervarar saga ch. 4-

nema sverð seljið, það er sló Dvalinn), of Freyja's splendid ornament

Brisingamen, celebrated also in Anglo-Saxon poetry (Sörla þáttur ch. 1). In

the poem Snjófríðardrápa, which is attributed to Harald Fairhair, the drapa

is likened to a work of art, which rings forth from beneath the fingers of

Dvalin (hrynr fram úr Dvalins greip; Flateybók., I. 582). This beautiful

poetical figure is all the more appropriately applied, since Dvalin was not

only the producer of the beautiful works of the smith, but also sage and

skald. He was one of the few chosen ones in time's morning who were

permitted to drink of Mimir's mead, which therefore is called his drink

(Dvalins drykkr - Skáldskaparmál 10).

In the earliest antiquity, no one partook of this drink who did not get it from Mimir himself.

In Hávamál 143, arrangements are made for spreading runic

knowledge among all kinds of beings. Odin taught them to his own clan; Dáinn

taught them to the Elves; Dvalinn among the dwarfs; Ásviðr among the giants.

Even the giants became participants in the good gift, which, mixed with

sacred mead, was sent far and wide. It has since been found among the Aesir,

among the Elves, among the wise Vanir, and among the children of men

(Sigrdrífumál 18). The same Dvalinn, who spread the runes to his clan of

ancient artists, is the father of daughters, who are in possession of

bjargrúnar (helping-runes) and who, together with Asynjes and Vana-disar,

employ them in the service of man (Fáfnismál 12-13).

Therefore Dvalin is one of the most ancient rune-masters, one of those who

brought the knowledge of runes to those beings of creation who were endowed

with reason (Hávamál 143). But all knowledge of runes came originally from

Mimir. As skald and runic scholar, Dvalin, therefore, stood in the relation

of disciple under the ruler of the lower world.

The myth in regard to the runes mentioned three apprentices, who afterwards

each spread the knowledge of runes among his own class of beings. Odin, who

in the beginning was ignorant of the mighty and beneficent rune-songs

(Hávamál 138-143), was Mimir's chief disciple by birth, and taught the

knowledge of runes among his kinsmen, the Aesir (Hávamál 143), and among

men, his protégés (Sigurdrífumál 18 - sumar hafa mennskir men “and living

men have some”). The other disciples were Dain (Dáinn) and Dvalin (Dvalinn).

Dain, like Dvalin, is an artist created by Modsognir (Völuspá 11, Hauksbók

and Gylfaginning). He is mentioned side by side with Dvalin, and like him he

has tasted the mead of poesy (munnvigg Dáins - in a verse composed by the

poet Sighvat, preserved in the Flateybók, among additions to Ólaf's sögu

helga). Dain and Dvalin taught the runes to their clans, that is, to elves

and dwarves (Hávamál 143). Nor were the giants neglected. They learned the

runes from Ásviðr. Since the other teachers of runes belong to the clans, to

which they teach the knowledge of runes - "Odin among Aesir, Dain among

elves, Dvalin among dwarves" - there can be no danger of making a mistake,

if we assume that Ásviðr was a giant. And as Mimir himself is a giant, and

as the name Ásviðr (= Ásvinr) means “friend of the Aesir”, and as no one -

particularly among the giants - has so much right as Mimir to this epithet,

which has its counterpart in Odin's epithet, Míms vinr (“Mimir's friend”),

then caution dictates that we keep open the highly probable possibility that

Mimir himself is meant by Ásviðr.

All that has here been stated about Dvalin shows that the

mythology has referred him to a place within the domain of Mimir's activity.

We have still to point out two statements in regard to him. Sol is said to

have been his leika (Alvíssmál 16 - kalla dvergar Dvalins leika;

cp. Nafnaþulur). Today, this is commonly interpreted to mean

'Dvalin's toy" and understood as a ironic reference to sunlight turning

dwarves to stone. However, that need not be the case. The word leika,

"plaything", as a feminine noun referring to a personal object, can mean a

young girl, a maiden, whom one keeps at his side, and in whose amusement one

takes part at least as a spectator. The examples which we have of the use of

the word indicate that the leika herself, and the person whose

leika she is, are presupposed to have the same home. Sisters are called

leikur, since they live together. Parents can call a

foster-daughter their leika. In the neuter gender, leika

means a plaything, a doll or toy, and even in this sense it can rhetorically

be applied to a person. In the same manner as Sol is called Dvalin's

leika, so the son of Nat and Delling, Dag, is called leikr Dvalins,

the lad or youth with whom Dvalin amused himself (Hrafnagaldur Óðins 24.)

Niflhel in the lower world has its counterpart in Niflheim in chaos.

Gylfaginning identifies the two (ch. 5 and 34). Hrafnagaldur Óðinns does the

same, and locates Niflheim far to the north in the lower world (norður

að Niflheim - st. 26), behind Yggdrasil's farthest root, under which

the poem makes the goddess of night, after completing her journey around the

heavens, rest for a new journey. When Night has completed such a journey and

come to the lower world, she goes northward in the direction towards

Niflheim, to remain in her hall, until Dag with his chariot gets down to the

western horizon and in his turn rides through the "horse doors" of Hades

into the lower world.

|

Dýrum settan |

24. Delling's son urged on his horse, well adorned with precious stones; The horse's mane glows above Man-world (Midgard). In his chariot, the steed draws Dvalin's playmate (the sun). |

|

Jörmungrundar |

25. At Jormungrund's northern horse-door under the outermost root of the noble Tree, to their couches went giantesses and giants dead men and dwarves and dark-elves. |

|

Risu raknar, |

26. The gods arose, Alfrodull (the sun) ran. Night advanced north toward Niflheim Ulfrun's son (Heimdall) lifted up Argjoll (his horn), the mighty hornblower in Himinbjorg. |

Thus the whole group of persons among whom Dvalin is placed -

Mimir, who is his teacher; Sol, who is his leika; Dag, who is his

leikr; Night, who is the mother of his leikr; Delling, who is the

father of his leikr - have their dwellings in Mimir's domain, and

belong to the subterranean class of divine beings in the Germanic religion.

From regions situated below Midgard's horizon, Night, Sol, and Dag draw

their chariots upon the heavens. On the eastern border of the lower world is

the point of departure for their regular journeys over the heavens of the

upper world ("the upper heavens," upphiminn - Völuspá 3;

Vafþrúðnismál 20, and elsewhere; uppheimur - Alvíssmál 12).

From this it follows that Niflhel is to be referred to the north of the

mountain Hvergelmir, Hel to the south of it. Thus this mountain is the wall

separating Hel from Niflhel. On that mountain is the gate, or gates, which

in the Gorm story separates Gudmund-Mimir's abode from those dwellings which

resemble a "cloud of vapor," and up there is the boundary, at which halir

die for the second time, when they are transferred from Hel to Niflhel.

The immense water-reservoir on the brow of the mountain, which stands under

Yggdrasil's northern root, as already stated, sends rivers down to

both sides - to Niflhel in the North and to Hel in the South. Of the

majority of these rivers we know nothing but their names. But those of which we

do know more are characterized in such a manner that we find that it is a

sacred land to which those flowing to the South towards Hel hasten their

course, and that it is an unholy land which is sought by those which send

their streams to the north down into Niflhel. The rivers Gjöll and Leiftur

fall down into Hel, and Gjöll is, as already indicated, characterized by a

bridge of gold, Leiftur by a shining, clear, and most holy water. Down there

in the South is found the mystic

hodd goða, surrounded by other Hel-rivers;

Baldur's and Lif and

Lifthrasir's citadel (perhaps identical with hodd goda);

Mimir's fountain, seven times overlaid with gold, the fountain of

inspiration and of the creative force, over which the "brilliant holy tree"

spreads its branches (Völuspá 27),

and around whose reed-wreathed edge the seed of poetry grows (Eilífr

Guðrúnarson, Skáldskaparmál 10, Jónsson edition); the Glittering Fields,

with flowers which never fade and with harvests which never are gathered;

Urd's fountain, over which Yggdrasil stands for ever green (Völuspá 20), and

in whose silver-white waters swans swim; and the sacred thing-stead of the

Aesir, to which they daily ride down over Bifrost. North of the mountain

roars the weapon-hurling Slíður, and doubtless is the same river as that in

whose "heavy streams" the souls of nithings must wade. In the North,

sólu fjarri ('far from the sun') stands, also at Nastrond, that

hall, the walls of which are braided of serpents (Völuspá 37). Thus Hel is

described as an Elysium, Niflhel with its subject regions as a realm of

unhappiness.

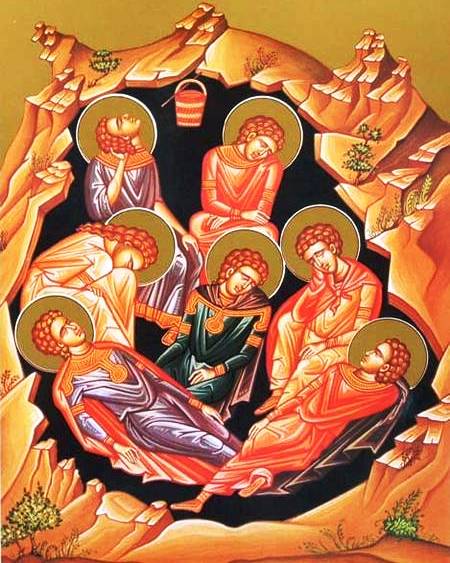

The Medieval Legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus

Christian legend concerning the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus may have its

chief, if not its only, root in a Germanic myth popularized in Europe in the

second half of the fifth or in the first half of the sixth century. At that time

large portions of the Germanic tribes had already been converted to

Christianity: the Goths, Vandals, Gepidians, Rugians, Burgundians, and Swabians

were Christians. Considerable parts of the Roman Empire were settled by the

Germans or governed by their swords. The Franks were on the point of entering

the Christian Church, and behind them the Alamannians and Longobardians. Their

myths and sagas were reconstructed so far as they could be adapted to the new

forms and ideas, and if they, more or less transformed, assumed the garb of a

Christian legend, then this guise enabled them to travel to the utmost limits of

Christendom; and if they also contained ideas that were not entirely foreign to

the Greek-Roman world, then they might the more easily acquire the right of

Roman nativity.

In its oldest form the legend of the “Seven Sleepers" takes the following form

in 587 AD in Gregory of Tours’ De Gloria Martyrum ("The Glory of the Martyrs”)

I. 92):

Seven brothers (‘germani’) have their place of rest near

the city of Ephesus, and the story of them is as follows: In the time of the

Emperor Decius, while the persecution of the Christians took place, seven men

were captured and brought before the ruler. Their names were Maximianus,

Malchus, Martinianus, Constantius, Dionysius, Joannes, and Serapion. All sorts

of persuasion was attempted, but they would not yield. The emperor, who was

pleased with their courteous manners, gave them time for reflection, so that

they should not at once fall under the sentence of death. But they concealed

themselves in a cave and remained there many days. Still, one of them went out

to get provisions and attend to other necessary matters. But when the emperor

returned to the same city, these men prayed to God, asking Him in His mercy to

save them out of this danger, and when, lying on the ground, they had finished

their prayers, they fell asleep. When the emperor learned that they were in the

above-mentioned cave, he, under divine influence, commanded that the entrance of

the cave should be closed with large stones, "for," said he, "as they are

unwilling to offer sacrifices to our gods, they must perish there." While this

transpired a Christian man had engraved the names of the seven men on a leaden

tablet, and also their testimony in regard to their belief, and he had secretly

laid the tablet in the entrance of the cave before the latter was closed. After

many years, the congregations having secured peace and the Christian Theodosius

having gained the imperial dignity, the false doctrine of the Sadducees, who

denied resurrection, was spread among the people. At this time it happens that a

citizen of Ephesus is about to make an enclosure for his sheep on the mountain

in question, and for this purpose he loosens the stones at the entrance of the

cave, so that the cave was opened, but without his becoming aware of what was

concealed within. But the Lord sent a breath of life into the seven men and they

arose. Thinking they had slept only one night, they sent one of their number, a

youth, to buy food. When he came to the city gate he was astonished, for he saw

the glorious sign of the Cross, and he heard people aver by the name of Christ.

But when he produced his money, which was from the time of Decius, he was seized

by the vendor, who insisted that he must have found secreted treasures from

former times, and who, as the youth made a stout denial, brought him before the

bishop and the judge. Pressed by them, he was forced to reveal his secret, and

he conducted them to the cave where the men were. At the entrance the bishop

then finds the leaden tablet, on which all that concerned their case was noted

down, and when he had talked with the men a messenger was dispatched to the

Emperor Theodosius. He came and kneeled on the ground and worshipped them, and

they said to the ruler: "Most august Augustus! There has sprung up a false

doctrine which tries to turn the Christian people from the promises of God,

claiming that there is no resurrection of the dead. In order that you may know

that we are all to appear before the judgment-seat of Christ according to the

words of the Apostle Paul, the Lord God has raised us from the dead and

commanded us to make this statement to you. See to it that you are not deceived

and excluded from the kingdom of God." When the Emperor Theodosius heard this he

praised the Lord for not permitting His people to perish. But the men again lay

down on the ground and fell asleep. The Emperor Theodosius wanted to make graves

of gold for them, but in a vision he was prohibited from doing this. And until

this very day these men rest in the same place, wrapped in fine linen mantles.”

However the historian of the Franks, Bishop Gregory of Tours (born 538 or 539), is the first one who presented in writing the legend regarding the seven sleepers. His story is a faithful translation of a tale found less than a century earlier in the homilies of Saint James of Sarugh (452-521 AD), a bishop in Syria, a region also well acquainted with Germanic tribes. His account is not written before the year 571 or 572. As the legend itself claims to date from the first years of the reign of Theodosius, it cannot be older than his kingdom, 379-395 AD.

The next time we learn anything about the seven sleepers in

occidental literature is in the Longobardian historian Paul the Deacon

(723-799 AD). What he relates has greatly surprised investigators; for

although he must have been acquainted with the Christian version in

regard to the seven men who sleep for generations in a cave, and

although he entertained no doubt as to its truth, he nevertheless

relates another - and a Germanic - seven sleepers' legend, the scene of

which he places in the remotest part of Germania. He narrates (I. 4):

"As my pen is still occupied

with Germany, I deem it proper, in connection with some other miracles,

to mention one which there is on the lips of everybody. In the remotest

western boundaries of Germany is to be seen near the sea-strand under a

high rock a cave where seven men have been sleeping no one knows how

long. They are in the deepest sleep and uninfluenced by time, not only

as to their bodies but also as to their garments, so that they are held

in great honor by the savage and ignorant people, since time for so many

years has left no trace either on their bodies or on their clothes. To

judge from their dress they must be Romans. When a man from curiosity

tried to undress one of them, it is said that his arm at once withered,

and this punishment spread such a terror that nobody has since then

dared to touch them. Doubtless it will some day be apparent why Divine

Providence has so long preserved them. Perhaps by their preaching - for

they are believed to be none other than Christians -- this people shall

once more be called to salvation. In the vicinity of this place dwell

the race of the Skritobinians ('the Ski-Finns')."

In chapter 6 Paul makes the following additions, which will be found to be of importance to our theme:

"Not far from that sea-strand which I

mentioned as lying far to the west (in the most remote Germany), where

the boundless ocean extends, is found the unfathomably deep eddy which

we traditionally call the navel of the sea. Twice a day it swallows the

waves, and twice it vomits them forth again. Often, we are assured,

ships are drawn into this eddy so violently that they look like arrows

flying through the air, and frequently they perish in this abyss. But

sometimes, when they are on the point of being swallowed up, they are

driven back with the same terrible swiftness."

From what Paul relates we learn that in the eighth century the

common belief ('on the lips of everybody') prevailed among the heathen

Germans that in the

neighborhood of that ocean-maelstrom, caused by Hvergelmir ("the roaring

kettle"), seven men slept from time immemorial under a rock. How far the

heathens believed that these men were Romans and Christians, or

whether this feature is to be attributed to a conjecture by Christianized

Germans, and came through influence from the Christian version of the

legend of the seven sleepers, is a question which it is not necessary to

discuss at present. That they are some day to awake to preach

Christianity to "the stubborn," still heathen Germanic tribes is

manifestly a supposition on the part of Paul himself, and he does not

present it as anything else. It has nothing to do with the saga in its

heathen form.

The first question now is: Has the heathen tradition in regard to the

seven sleepers, which, according to the testimony of the Longobardian

historian, was common among the heathens of the eighth century,

since then disappeared without leaving any traces in our mythic records?

The answer is: Traces of it reappear in Saxo, in Adam of Bremen, in Norse and German popular belief, and in Völuspá. When compared with one another these traces are sufficient to determine the character and original place of the tradition in the epic of the Germanic mythology.

In Saxo's account of King Gorm's and Thorkil's journey to and in the lower world, they and their companions are permitted to visit the abodes of the damned and the fields of bliss, along with the world-fountains, and to see the treasures preserved in their vicinity. In the same realm where these fountains are found there is, says Saxo, a tabernaculum within which still more precious treasures are preserved. It is an uberioris thesauri secretarium, "a private chamber with a yet richer treasure." The Danish adventurers also entered here. The treasury was also an armory, and contained weapons suited to be borne by warriors of superhuman size. The owners and makers of these arms were also there, but they were perfectly quiet and as immovable as lifeless figures. Still they were not dead, but made the impression of being half-dead (semineces). By the enticing beauty and value of the treasures, and partly, too, by the dormant condition of the owners, the Danes were betrayed into an attempt to secure some of these precious things. Even the usually cautious Thorkil set a bad example and put his hand on a garment (amiculo manum inserens). We are not told by Saxo whether the garment covered anyone of those sleeping in the treasury, nor is it directly stated that the touching with the hand produced any disagreeable consequences for Thorkil. But further on Saxo relates that Thorkil became unrecognizable, because a withering or emaciation (marcor) had changed his body and the features of his face.

With this account in Saxo we must compare what we read in Adam of Bremen (Book 4) about the Frisian adventurers who tried to plunder treasures belonging to giants who in the middle of the day lay concealed in subterranean caves (meridiano tempore latitantes antris subterraneis). This account must also have conceived the owners of the treasures as sleeping while the plundering took place, for not before they were on their way back were the Frisians pursued by the plundered party or by other lower-world beings. Still, all but one succeeded in getting back to their ships. Adam asserts that they were such beings quos nostri cyclopes appellant ("which among us are called cyclops"), that they, in other words, were gigantic smiths, who accordingly themselves had made the untold amount of golden treasures which the Frisians saw there. These northern cyclops, he says, dwelt within solid walls, surrounded by a water, to which, according to Adam of Bremen, one first comes after traversing the land of frost (provincia frigoris), and after passing that Euripus, "in which the water of the ocean flows back to its mysterious fountain" (ad initia quaedam fontis sui arcani recurrens), "this deep subterranean abyss wherein the ebbing streams of the sea, according to report, were swallowed up to return," and which "with most violent force drew the unfortunate seamen down into the lower world" (infelices nautos vehementissimo impetu traxit ad Chaos).

It is evident that what Paul the Deacon, Adam of Bremen, and Saxo here relate must be referred to the same tradition. All three refer the scene of these strange things and events to the "most remote part of Germany". According to all three reports, the boundless ocean washes the shores of this saga-land which has to be traversed in order to get to "the sleepers," to "the men half-dead and resembling lifeless images," to "those concealed in the middle of the day in subterranean caves." Paul assures us that they are in a cave under a rock in the neighborhood of the famous maelstrom which sucks the billows of the sea into itself and spews them out again. Adam makes his Frisian adventurers come near being swallowed up by this maelstrom before they reach the caves of treasures where the cyclops in question dwell; and Saxo locates their tabernacle, filled with weapons and treasures, to a region which we have already recognized as belonging to Mimir's lower-world realm, and situated in the neighborhood of the sacred subterranean fountains (See Gudmund of Glæsisvellir).

In the northern part of Mimir's domain, consequently in the

vicinity of the Hvergelmir fountain, from and to which all waters find

their way, and which is the source of the famous maelstrom, there

stands, according to Völuspá 37, a golden hall in which Sindri's kinsmen

have their home. Sindri is, as we know, like his brother Brokk and

others of his kinsmen, an artist of antiquity, a cyclops, to use the

language of Adam of Bremen. The Northern records and the Latin

chronicles thus correspond in the statement that in the neighborhood of

the maelstrom or of its subterranean fountain, beneath a rock and in a

golden hall, or in subterranean caves filled with gold, certain men who

are subterranean artisans dwell. Paul the Deacon makes a "curious"

person who had penetrated into this abode disrobe one of the sleepers

clad in "Roman" clothes, and for this he is punished with a withered

arm. Saxo makes Thorkil put his hand on a splendid garment which he sees

there, and Thorkil returns from his journey with an emaciated body, and

is so lean and lank as not to be recognized.

The legend has preserved the connection found in the myth between the

above meaning and the idea of a resurrection of the dead. But in the

myth concerning Mimir's seven sons (the seven dwarves) this idea is most

intimately connected with the myth itself, and is, with epic logic,

united with the whole mythological system. In the legend, on the other

hand, the resurrection idea is put on as a trade-mark. The seven men in

Ephesus are lulled into their long sleep, and are waked again to appear

before Theodosius, the emperor, to preach a sermon illustrated by their

own fate against the false doctrine which tries to deny the resurrection

of the dead.

Gregorius says that he is the first who recorded in the Latin language

this miracle, as yet unknown to the Church of Western Europe. As his

authority he quotes "a certain Syrian" who had interpreted the story for

him. The story appeared in several Syrian sources before Gregory's

lifetime (Jacob of Sarug in Acta Santorum, Symeon Metaphrastes, Land's

Anecdota, iii. 87ff, Barhebraeus, Chron. eccles. i. 142ff., and

Assemani, Bib. Or. i. 335ff.). Another 6th-century version, in a Syrian

manuscript in the British Museum (Cat. Syr. Mss, p. 1090), gives eight

sleepers. There are considerable variations as to their names.

Even so, the contents may well be borrowed from the Germanic mythology. That Syria or Asia Minor was the scene of its transformation into a Christian legend is possible, and is not surprising. During and immediately after the time to which the legend itself refers the resurrection of the seven sleepers, the time of Theodosius, the Roman Orient, Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt were full of Germanic warriors who had permanent quarters there. A Notitia dignitatu [Register of Dignitaries] from this age speaks of hosts of Goths, Alamannians, Franks, Chamavians, and Vandals, who there had fixed military quarters. There then stood an ala Francorum, a cohors Alamannorum, a cohors Chamavorum, an ala Vandilorum, a cohors Gothorum, and no doubt there, as elsewhere in the Roman Empire, great provinces were colonized by Germanic veterans and other immigrants. Nor must we neglect to remark that the legend refers the falling asleep of the seven men to the time of Decius. Decius fell in battle against the Goths, who, a few years later, invaded Asia Minor and captured among other places also Ephesus. The influence of the Germanic tribes in this region is confirmed by Gibbons in his Of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Míms Sýnir: The Sons of Mimir

In Skáldskaparmál 43, Loki pits two rival bands of smiths

against each other. They are the Sons of Ivaldi and the brothers, Brokk and

Sindri. The latter forge Thor’s hammer Mjöllnir, and thereby win the competition.

Völuspá 36 informs us that Sindri's golden hall stands on Nidavellir, "Nidi's

plains" near the giant Brimir (Mimir or Ymir's) beer-hall in Hel. There are

compelling reasons for assuming that the ancient artisans Brokk and Sindri are

identical with Dáinn and Dvalinn, the ancient artisans created by Mimir. This

conclusion is based on the following:

Dvalinn is mentioned by the side of Dáinn both in Hávamál 143 and in Grímnismál

33; also in the sagas, where they make treasures in company. Both the names are

clearly epithets which point to the mythic destiny of the ancient artists in

question. Dáinn means "the dead one," and in analogy with this we must interpret

Dvalinn as "the dormant one," "the one slumbering" (cp. the Old Swedish dvale,

sleep, unconscious condition). Their fates have made them the representatives of

death and sleep, a sort of equivalent of the Greek Thanatos and Hypnos.

In Hyndluljóð 7, the artists who made Frey's golden boar are called Dáinn and

Nabbi. In the Prose Edda (Skáldskaparmál 43) they are called Brokk and Sindri.

Thus we arrive at the following parallels:

Dáinn and Dvalinn made treasures together;

Brokk and Sindri made Frey's golden boar;

Dáinn and Nabbi made Frey's golden boar;

and the conclusion we draw from this is that in our mythology, in which there is

such a plurality of names, Dvalinn, Sindri, and Nabbi are the same person, and

that Dáinn and Brokk are identical. It should be noted that while Dáinn while is

found as the name for a grazing four-footed animal in Grímnismál 33, that

Brokkur too has a similar signification (See Vigfusson, Dictionary, where Brokkr

is defined as "trotter" i.e. a horse from the verb brokka, to trot, a word of

foreign origin). This may point to an original identity of these epithets.

Below, I will present further evidence of this identity.

It has already been demonstrated that Dvalinn is a son of Mimir. Sindri-Dvalin

and his kinsmen are therefore Mimir's offspring (Míms synir—Völuspá 45). The golden citadel

situated near the fountain of the maelstrom is therefore inhabited by the sons

of Mimir.

According to Sólarljóð 56, the sons of Niði come toward Hel from this region

(from the north in Mimir's domain). They are seven in number, as are the

famous band of dwarves in Grimm's fairy-tales:

Norðan sá eg ríða

Niðja sonu,

og voru sjö saman;

hornum fullum

drukku þeir inn hreina mjöð

ór brunni Baugregins.

From the North I saw ride

Nidi's sons,

They were seven together;

from full horns,

the pure mead they drank

from the ring-maker's well.

The name Nidi appears three times in Völuspá, first in the dwarf-list (st. 11).

Völuspá 37 places the golden hall of the master-artist Sindri (who forged

Mjöllnir for Thor) on Nidavellir, "Nidi's plains". Nearby, it also locates the

"beer-hall" of the giant Brimir, an alternate name of both Ymir and his son

Mimir. In Völuspá 66, Nidhögg (the serpent mentioned along with the four harts

in Grímnismál 33) flies up from Nidafjöll ('Nidi's mountains'), the dividing

wall between Hel and Niflhel. As the ruler of this land, Mimir himself

must be Nidi, "the lower one".

In the same region Mimir's daughter Night has her hall, where

she takes her rest after her journey across the heavens is done. As

Mimir's son, Dvalin, "the sleeper," is Night's brother. Her citadel is

probably identical with the one in which Dvalin and his brothers sleep.

According to Saxo (Book 8), voices of women are heard in the

tabernaculum glittering with weapons and treasures, belonging to

men who sleep among weapons too large for those of human stature, when

Thorkil and his men come to plunder the treasures there. If not the

voices of Night and her sisters, then those of the wave-giantesses who

turn the great

World-Mill. Solarljóð 57 and 58 speak of these tormented women,

slaving near Hvergelmir under Yggdrasil's northern root.

Night has her court and her attendant sisters in the Germanic mythology,

the daughters of Gudmund-Mimir are said to be twelve in number. The

"sleeping castle" of Germanic mythology is therefore situated in Night's

native land.

Mimir, as we know, was the ward of the middle root of the world-tree. His seven sons, representing the changes experienced by the world-tree and nature annually, have with him guarded and tended the holy tree and watered its root with aurgum forsi from the subterranean horn, "Valfather's pledge.' [Völuspá 27 and 28]. When the god-clans became foes, and the Vanir seized weapons against the Aesir, Mimir was slain, and the world-tree, losing its wise guardian, became subject to the influence of time. It suffers in crown and root (Grímnismál), and as it is ideally identical with creation itself, both the natural and the moral, so toward the close of the period of this world it will exhibit the same dilapidated condition as nature and the moral world then are to reveal.

Logic demanded that when the world-tree lost its chief ward, the lord of the well of wisdom, it should also lose that care which under his direction was bestowed upon it by his seven sons. These, voluntarily or involuntarily, retired, and the story of the seven men who sleep in the citadel full of treasures informs us how they thenceforth spend their time until Ragnarok. The details of the myth telling how they entered into this condition cannot now be found; but it may be in order to point out, as a possible connection with this matter, that one of the older Vanir, Njörd's father, and possibly the same as Mundilfari, had the epithet Svafur, Svafurþorinn (Fjölsvinnsmál 8). Svafur means sopitor, the sleeper, and Svafurþorinn seems to refer to svefnþorn, "sleep-thorn." According to the traditions, a person could be put to sleep by laying a "sleep-thorn" in his ear, and he then slept until it was taken out or fell out, (Hrólfs saga kraka ok kappa hans ch. 7 and in Fáfnismál 43).

Popular traditions scattered over Sweden, Denmark, and

Germany have to this very day been preserved, on the lips of the common

people, of the men sleeping among weapons and treasures in underground

chambers or in rocky halls. A Swedish tradition makes them equipped not

only with weapons, but also with horses which in their stalls abide the

day when their masters are to awake and sally forth. Common to the most

of these traditions, both the Northern and the German, is the feature

that this is to happen when the greatest distress is at hand, or when

the end of the world approaches and the day of judgment comes. Jakob

Grimm in his Deutsche Mythologie, chapter 32, discusses the various

legends of heroes sleeping in hills. Of special importance to the

subject under discussion, the popular tradition in certain parts of

Germany seems to have preserved a feature from the heathen myths. When

the heroes who have slept through centuries awake and come forth, the

trumpets of the last day sound and a great battle with the powers of

evil is imminent, an immensely old tree, which has withered, grows green

again, and a happier age begins. The same concepts are contained in the

Ragnarök sequence at the end of Völuspá.

This immensely old tree, which is withered at the close of the present

period of the world, and which is to become green again in a happier age

after a decisive conflict between the good and evil, can be no other

than the world-tree of Germanic mythology, the Yggdrasil of our Eddas.

The angel trumpets, at whose blasts the men who sleep within the

mountains sally forth, have their prototype in Heimdall's horn, which

proclaims the destruction of the world; and the battle to be fought is

the Ragnarök conflict, clad in Christian robes, between the gods and the

destroyers of the world.

Here Mimir's seven sons also have their task to perform. The last great struggle also concerns the lower world, whose regions of bliss demand protection against the thurs-clans of Niflhel, the more so since these very regions of bliss constitute the new earth, which after Ragnarok rises from the sea to become the abode of a better race of men. The "wall rock" of the Hvergelmir fountain, known as Nidafjöll ("Nidi's mountains') and its "stone gates" (Völuspá 48 - veggberg, steindyr) require defenders able to wield those immensely large swords which are kept in the sleeping castle on Night's native land, and Sindri-Dvalin is remembered not only as the artist of antiquity, spreader of Mimir's runic wisdom, enemy of Loki, and father of the man-loving dises, but also as a hero. The name of the horse he rode, and probably is to ride in the Ragnarök conflict, is, according to a strophe cited in Skáldskaparmál 72, Móðinn.

This seems to underpin the sense of Völuspá 45: Leika Míms synir,

en mjötuður kyndist

að inu gamla

Gjallarhorni;

hátt blæs Heimdallur,

horn er á lofti. "Mimir's sons spring up,

for the fate of the world

is proclaimed by the old

Gjallarhorn.

Loud blows Heimdall

-- the horn is raised."

We have previously seen the word leika associated with Mimir’s

son Dvalinn. Sol is his leika, play-thing. In regard to

leika, it is to be remembered that its older meaning, "to jump,"

"to leap," "to fly up," reappears not only in Ulfilas, who translates

skirtan of the New Testament with laikan. (Luke I. 41, 44, and

VI. 23; in the former passage in reference to the child slumbering in

Elizabeth's womb; the child "leaps" at her meeting with Mary), but also

in another passage in Völuspá, where it is said in regard to Ragnarok,

leikur hár hiti við himin sjálfan -- "high leaps" (plays) "the

fire against heaven itself." Further, we must point out the preterit

form kyndisk (from kynna, to make known) by the side of the present form

leika. This juxtaposition indicates that the sons of Mimir "rush

up," while the fate of the world, the final destiny of creation in

advance and immediately beforehand, was proclaimed "by the old

Gjallarhorn." The bounding up of Mimir's sons is the effect of the first

powerful blast. One or more of these follow: "Loud blows Heimdall -- the

horn is raised; and Odin speaks with Mimir's head." Thus we have found

the meaning of leika Míms synir. Their waking and appearance is one of

the signs best remembered in the chronicles in popular traditions of

Ragnarok's approach and the return of the dead, and in this strophe

Völuspá has preserved the memory of the "sleeping castle" of Germanic

mythology.

Thus a comparison of the mythic fragments extant with the popular

traditions gives us the following outline of the Germanic myth

concerning the seven sleepers:

The world-tree -- the representative of the physical and moral laws of

the world -- grew in time's morning gloriously out of the fields of the

three world-fountains, and during the first epochs of the mythological

events (ár alda) it stood fresh and green, cared for by the

subterranean guardians of these fountains. But the times became worse.

Gullveig-Heid, spreads evil runes in Asgard and Midgard, and she causes

a dispute and war between those god-clans whose task it is to watch over

and sustain the order of the world in harmony. In the war between the

Aesir and Vanir, the middle and most important world-fountain -- the

fountain of wisdom, the one from which the good runes were drawn --

became robbed of its watchman. Mimir was slain, and his seven sons, the

superintendents of the seven seasons, who saw to it that these

season-changes followed each other within the limits prescribed by the

world-laws, were put to sleep, and fell into a stupor, which continues

throughout the historical time until Ragnarok. Consequently the

world-tree cannot help withering and growing old during the historical

age. Still it is not to perish. Neither fire nor sword can harm it; and

when evil has reached its climax, and when the present world is ended in

the Ragnarok conflict and in Surt's flames, then it is to regain that

freshness and splendor which it had in time's morning.

Until that time Sindri-Dvalin and Mimir's six other sons slumber in that

golden hall which stands toward the north in the lower world, on Mimir's

fields. Nott, their sister, dwells in the same region, and shrouds the

chambers of those slumbering in darkness. Standing toward the north

beneath the Nida mountains, the hall is near Hvergelmir's fountain,

which causes the famous maelstrom. As sons of Mimir, the great smith of

antiquity, the seven brothers were themselves great smiths of antiquity,

who, during the first happy epoch, gave to the gods and to nature the

most beautiful treasures (Mjölnir, Brisingamen, Gullinbursti, Draupnir).

The hall where they now rest is also a treasure-chamber, which preserves

a number of splendid products of their skill as smiths, and among these

are weapons, too large to be wielded by human hands, but intended to be

employed by the brothers themselves when Ragnarok is at hand and the

great decisive conflict comes between the powers of good and of evil.

The seven sleepers are there clad in splendid mantles of another cut

than those common among men. Certain mortals have had the privilege of

seeing the realms of the lower world and of inspecting the hall where

the seven brothers have their abode. But whoever ventured to touch their

treasures, or was allured by the splendor of their mantles to attempt to

secure any of them, was punished by the drooping and withering of his

limbs.

When Ragnarok is at hand, the aged and abused world-tree

trembles, and Heimdall's trumpet, until then kept in the deepest shade

of the tree, is once more in the hand of the god, and at a

world-piercing blast from this trumpet Mimir's seven sons start up from

their sleep and arm themselves to take part in the last conflict. This

is to end with the victory of the good; the world-tree will grow green

again and flourish under the care of its former keepers; "all evil shall

then cease, and Baldur shall come back." The Germanic myth in regard to

the seven sleepers is thus most intimately connected with the myth

concerning the return of the dead Baldur and of the other dead men from

the lower world, with the idea of resurrection and the regeneration of

the world. It forms an integral part of the great epic of Germanic

mythology, and could not be spared. If the world-tree is to age during

the historical epoch, and if the present period of time is to progress

toward ruin, then this must have its epic cause in the fact that the

keepers of the chief root of the tree were severed by the course of

events from their important occupation. Therefore Mimir dies; therefore

his sons sink into the sleep of ages. But it is necessary that they

should wake and resume their occupation, for there is to be a

regeneration, and the world-tree is to bloom with new freshness.

Dvalinn is mentioned by the side of Dáinn both in Hávamál 143 and in

Grímnismál 33; also in the Fornaldarsagas, where they make treasures in

company. Both the names are clearly epithets which point to the mythic

destiny of the ancient artists in question. Dáinn means "the dead one,"

and in analogy with this we must interpret Dvalinn as "the dormant one,"

"the one slumbering" (cp. the Old Swedish dvale, sleep,

unconscious condition). Their fates have made them the representatives

of death and sleep, a sort of equivalent of the Greek Thanatos and

Hypnos. As such they appear in the allegorical strophes incorporated in

Grímnismál 33, which, describing how the world-tree suffers and grows

old, make Dáinn and Dvalinn, "death" and "slumber," get their food from

its branches, while Nidhogg and other serpents devour its roots.

From a 17th century mss. of the Poetic Edda

AM 738 4to, Árni Magnússon Institute, Iceland.

[PREVIOUS][MAIN][NEXT]

[HOME]