The Master and the Mistress of

THE WILD HUNT

ODIN'S WIFE:

Mother Earth in Germanic Mythology

[HOME]

| HISTORIC BELIEF IN THE WILD HUNT |

In 1673, Johannes Scheffer author of Lapponia, describes belief in the Wild Hunt, by the Laplanders (Sami) in his day. His account includes details of an offering made by the people to the so-called “Yule Folk”:

“They believe Thirdly, That there is a certain kind of good and evil Genius's, wandring in the Air, especially about Christmas Eve, of which we have said something before. The before-mentioned Author speaking of certain Sacrifices they used to offer to them lays: Those they offer to the Juhlian Company, which they suppose are wandring, about that time in the Air. These they call the Juhlian Company deriving their Name from the word Juhli (Yule), which now signifies as much as the Feast of the Nativity of Christ, but in former Ages was used for the time of the new Year, as I have sufficiently demonstrated in my Treatise of Upsal. But it being their Opinion, that more especially about this time the Air is filled with Spectres and Genius's, they have given it this Name.The Wild Hunt, or Furious Host, called the Juhlfolket or Yule Folk by the Lapps are well-known across Northern Europe and are thought to originate from heathen times.

“Besides those three Gods (i.e. Thor, Storjunkare and the Sun), which are accounted of the first Rank, they have others of a lower Degree, as we have shewn before; especially the Manes of the Dead, and the Juhlian Company. They don't give any particular Names to those Ghosts, but in general call them Sitte. Neither do they erect them any Images, as they do to Thor and Storjunkare, only they offer them some certain Sacrifices.

“We will now come to the Juhlian Company, whom, as I have shewn before, they call Juhlafolket [Yule Folk]. These, as well as the Ghosts, have no Statues or Images allotted for their Worship, the Place where they are worshipped being a Tree, at about a Bow shot from the back-side of their Huts. They likewise worship them by Sacrifices, a Description of which has been left us by Samuel Rheen, in the following Words; The Day before the Feast of the Juhlian Company, being Christmass-Eve, and on Christmass-Day it self, they offer superstitious Sacrifices, in Honour of the Juhlian Company, whom they suppose wandring at that time thro' the neighbouring Forests and Mountains. The manner thus: On Christmass-Eve they Fast, or rather abstain from all sorts of Flesh; but of every thing else they eat, they carefully preserve a small quantity. The same they perform on Christmass Day, when they live very Plentiful. All the Bits they have preserved for these two Days, they put in a small Chest made of the Bark of Birch, in the shape of a Boat, with its Sails and Oars; they pour also some of the Fat of the Broth upon it, and thus hang it on a Tree, about a Bow Shot distant from the backside of their Huts, for the use of the Juhlian Company, wandring at that time about the Forests, Mountains, and the Air. Thus we have also given you an account of this kind of sacrifices, which resemble in a great measure the Libations of the Ancients to their Genius's. But why they do this in a Boat, they know not, nor can give the least reason for it. In my Opinion, this seems to intimate, that they had it first from foreign Parts, where perhaps they used to pay a certain Reverence to the Company of Angels, who brought the News of Christ's Birth; as I told you before, of this they could not be inform'd but by Christians, who probably might come thither in ancient Times by Sea and consequently in Vessels. So much concerning the Idolatry and superstitious Worship of the Lapland Gods, which is continued to this Day, if not by all, at least among a great many of the Laplanders, as far as we have been able to discover them by the experience and inquiry of those, who have frequented and lived a considerable time in these Parts.”

1902 P. D. Chantepie de la Saussaye, The Religion of the Teutons, Vol. II:

The conception of the Wild Hunt or the Furious Host plays an important part in popular belief. Since the Middle Ages, such conceptions are met with under various names, the former more commonly in North, the latter in South, Germany.

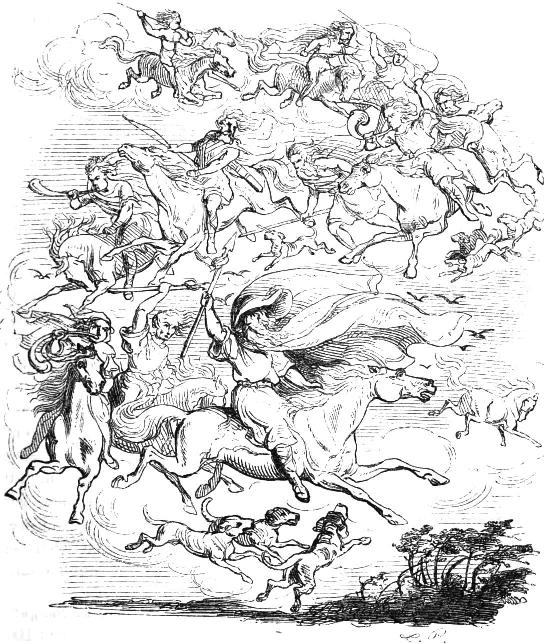

The general notion underlying this conception may easily be determined. In the raging and howling of the tempest the wild hunter and his train are recognized. This hunter is usually Wodan, the god of the wind, who is at the same time the god of the dead. This train is made up of the souls of the departed. Dying we find occasionally designated as "joining the old host." While the elements that enter into the conception are therefore two in number, the wind and the company of souls, there have not only been added a number of other features, but in many places and in various localities the conception has assumed a special character. In one place the train issues from a particular mountain, in another particular individuals are designated as forming a part of it.

…We do not, of course, claim that the enormous mass of material gathered on this subject in the way of popular tales and stories, of observances and superstitions, admits of strictly historical arrangement. Nor is it maintained that all of it, as existing in the Christian Middle Ages and in the life of the peasantry in modern times, has been handed down from Teutonic heathendom. The popular imagination has given further development to an already existing germ. It is clear, at any rate, that in this Wild Hunt the great "hell-hunter," Wodan, still survives among the people. If not necessarily, the Wild Hunt is at least frequently, directly connected with the god Wodan, and the whole conception attains among the Teutons a vividness, clearness, and variety that is equalled nowhere else. The historical element in folklore, therefore, implies that, apart from the numerous historical reminiscences to be found in the hunt or the host, one or more of its members may be identified with persons of whose memory the people still stand in awe.1895 Hélène Adeline Guerber, Myths of the Northern Lands:

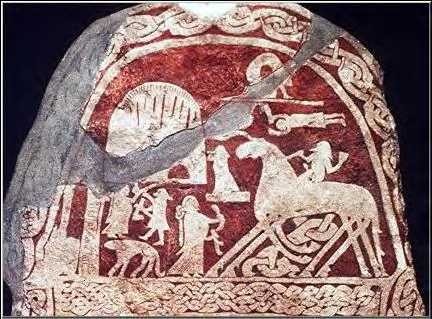

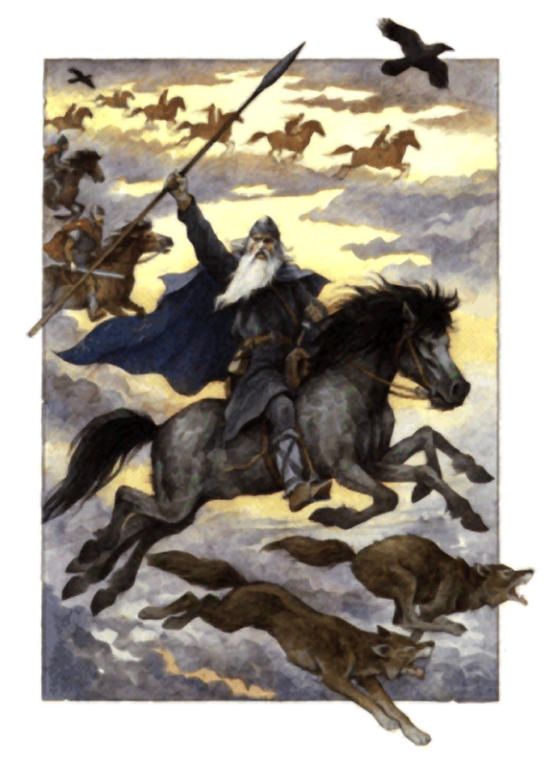

Odin, as wind god, generally rode about on his eight-footed steed Sleipnir, a habit which gave rise to the oldest Northern riddle, which runs as follows: “Who are the two who ride to the Thing? Three eyes have they together, ten feet, and one tail; and thus they travel through the lands.” And as the souls of the dead were supposed to be wafted away on the wings of the storm, Odin was worshiped as the leader of all disembodied spirits. In this character he was most generally known as the Wild Huntsman, and when people heard the rush and roar of the wind they cried aloud in superstitious fear, fancying they heard and saw him ride past with his train, all mounted on snorting steeds, and accompanied by baying hounds. And the passing of the Wild Hunt, known as Woden’s Hunt, the Raging Host, Gabriel’s Hounds, or Asgardreia (Asgard Ride), was also considered a presage of misfortune of some kind, such as pestilence or war.

People further fancied that if any were so sacrilegious as to join in the wild halloo in mockery, they were immediately snatched up and whirled away with the vanishing host, while those who joined in the halloo with implicit good faith were rewarded for their credulity by the sudden gift of a horse’s leg, hurled at them from above, which, if they carefully kept until the morrow, was changed into a solid lump of gold.

Even after the introduction of Christianity the ignorant Northern people still dreaded the on-coming storm, declaring that it was the Wild Hunt sweeping across the sky.

Sometimes it left behind it a small black dog, which, cowering and whining upon a neighboring hearth, had to be kept for a whole year and carefully tended unless the people succeeded in exorcising it or frightening it away. The usual recipe, the same as for the riddance of changelings, was to brew beer in egg-shells, which performance so startled the spectral dog that he fled with his tail between his legs, exclaiming that, although as old as the Behmer, or Bohemian forest, he had never yet seen such an uncanny sight. “I am as old As the Behmer wold, And have in my life such a brewing not seen.” (Thorpe's tr).

The object of this phantom hunt varied greatly, and was either a visionary boar or wild horse, white-breasted maidens who were caught and borne away bound only once in seven years, or the wood nymphs, called Moss Maidens, who were thought to represent the autumn leaves torn from the trees and whirled away by the wintry gale. In the middle ages, when the belief in the old heathen deities was partly forgotten, the leader of the Wild Hunt was no longer Odin, but Charlemagne, Frederick Barbarossa, King Arthur, or some Sabbath breaker, like the squire of Rodenstein or Hans von Hackelberg, who, in punishment for his sins, was condemned to hunt forever through the realms of air.

As the winds blew fiercest in autumn and winter, Odin was supposed to hunt in preference during that season, especially during the time between Christmas and Twelfth-night, and the peasants were always careful to leave the last sheaf or measure of grain out in the fields to serve as food for his horse.

This hunt was of course known by various names in the different countries of northern Europe; but as the tales told about it are all alike, they evidently originated in the same old heathen belief, and to this day ignorant people of the North still fancy that the baying of a hound on a stormy night is an infallible presage of death.

The Wild Hunt, or Raging Host of Germany, was called Herlathing in England, from the mythical king Herla, its supposed leader; in northern France it bore the name of Mesnée d’Hellequin, from Hel, goddess of death; and in the middle ages it was known as Cain’s Hunt or Herod’s Hunt, these latter names being given because the leaders were supposed to be unable to find rest on account of the iniquitous murders of Abel, of John the Baptist and of the Holy Innocents.

In central France the Wild Huntsman, whom we have already seen in other countries as Odin, Charlemagne, Barbarossa, Rodenstein, von Hackelberg, King Arthur, Hel, one of the Swedish kings, Gabriel, Cain, or Herod, is also called the Great Huntsman of Fontainebleau (le Grand Veneur (la Fantaz'nebleau), and people declare that on the eve of Henry IV.’s murder, and also just before the outbreak of the great French Revolution, his shouts were distinctly heard as he swept across the sky.

1900 The International Cyclopaedia: A Compendium of Human Knowledge, Volume 15:

WILD HUNT (Ger. wilde or wüthende jagd; also wildes or witthendet heer, wild or maddening host; nachtjäger, night huntsman, etc.), the name given by the German people to a fancied noise sometimes heard in the air at night, as of a host of spirits rushing along over woods, fields, and villages, accompanied by the shouting of huntsmen and the baying of dogs. The stories of the wild huntsman are numerous and widespread: although varying in detail, they are uniform in the essential traits, and betray numerous connections with the myths of the ancient gods and heroes. The root of the whole notion is most easily discernible in the expression still used by the peasants of lower Germany when they hear a howling in the air, '' wode hunts" (Wodejaget), that is, Wodan or Odin marches, as of old, at the head of his battle-maidens, the Walkyries, and of the heroes of Walhalla; perhaps, too, accompanied by his wolves, which, according to the myth, along with his ravens, followed him, taking delight in strife, and pouncing upon the bodies of the fallen. The heathen gods were not entirely dislodged from the imagination of the people by Christianity, but they were banished from all friendly communication with men, and were degraded to ghosts and devils. Yet some of the divine features are still distinctly recognizable. As the celestial god Wodan, the lord of all atmospheric and weather phenomena, and consequently of storms, was conceived as mounted on horseback, clad with a broad-rimmed hat shading the face, and a wide dark cloak; the wild huntsman also appears on horseback, in hat and cloak, and is accompanied by a train of spirits, though of a different stamp—by the ghosts of drunkards, suicides, and other malefactors, who are often without heads, or otherwise shockingly mutilated. One constant trait of the stories shows how effectually the church had succeeded in giving a hellish character to this ghost of Wodan—when he comes to a crossroad, he falls, and gets up on the other side. On very rare occasions, the wild huntsman shows kindness to the wanderer whom he meets; but generally he brings hurt or destruction, especially to any one rash enough to address him, or join in the hunting cry, which there are many narratives of persons in their cups having done. Whoever remains standing in the middle of the highway, or steps aside into a tilled field, or throws himself in silence on the earth, escapes the danger. In many districts, heroes of the older or of the more modern legends take the place of Odin; thus, in Lusatia and Orlagau, Berndietrich, that is, Dietrich of Bern; in lower Hesse, Charles the Great; in England, King Arthur; in Denmark, King Waldemar. The legend has also in recent times attached itself to individual sportsmen, who, as a punishment for their immoderate addiction to sport, or for the cruelty they were guilty of in pursuing it, or for hunting on Sunday, were believed to have been condemned henceforth to follow the chase by night. In lower Germany, there are many such stories current of one Hakkelberend, whose tomb even is shown in several places. Still, the very name leads back to the myth of Wodan, for Hakkelberend means literally the mantle-bearer (from O. H. Ger. hakhul; O. Norse, häkull or hekla; Ang.-Sax. haeele, drapery, mantle, armor; and bär, to bear). The appearing of the wild hunter is not fixed to any particular season, but It occurs frequently and most regularly in the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany.

Another version of the wild hunt is to be found in the legend prevalent in Thuringia and the district of Mansfeld. There the procession, formed partly of children who had died unbaptized, and headed by Frau Holle or Holda (see Berchta), passed yearly through the country on holy Thursday, and the assembled people waited its arrival, as if a mighty king were approaching. An old man, with white hair, the faithful Eckhart (see Tannhauser and Venusberg), preceded the spirit-host, to warn the people out of the way, and even ordered some to go home, so that they might not come to hurt. This is the benign goddess, the wife of Wodan, who, appearing under various names, travels about through the country during the sacred time of the year. This host of Holda or Berchta also prefers the season about Epiphany. In one form or other, the legend of the wild hunt is spread over all German countries, and is found even In France and Spain.1900 Harriet Murray-Aynsley, Symbolism of the East and West:

“The name Woden or Wuotan denotes the strong and furious goer: Gothic, Wods; Norwegian, ódr, enraged. According to this view, the name may therefore be closely allied to the Lowland Scotch word wud, mad or furious. A Jacobite song of 1745 says, ‘the women are a' gane wud.’ There is also a Scotch proverb, ‘Dinna put a knife into a wud man's hand.’ Odin, as the storm god, may well be supposed to have ridden like one wud: he has been considered to be the Wild Huntsman of the German legends. If so, the legend of the Erl King or Wild Huntsman probably came from the same source as Odin's Wild Hunt. He, and his wife Frigga, are fabled to have had two sons, Baldr and Hodr. The tale runs thus: Frigga had made all created things swear that they would never hurt Baldr, ‘that whitest and most beloved of the gods; ‘however there was one little shoot ‘that groweth East of Valhalla, so small and delicate that she forgot to take its oath.’ It was the mistletoe, and with a branch of that feeble plant, flung by the hand of the blind Hodr, Baldr was struck dead. He then descended into the gloomy snake-covered Helheim, whither Hermod (Baldr's brother) made a violent but unsuccessful ride, mounted on Sleipner, his father's horse, in order to obtain his brother's body. The Hel Jagd, as it is called in some parts of Germany, has by others been styled the English Hunt. Both refer to the nether world; we have already seen that Great Britain was formerly supposed to be the Land of Departed Souls.”

ODIN THE MASTER OF THE WILD HUNT |

Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology, Chapter 7:

The highest, the supreme divinity, universally honoured, as we have a right to assume, among all Teutonic races, would in the Gothic dialect have been called Vôdans; he was called in OHG. Wuotan, a word which also appears, though rarely, as the name of a man: Wuotan, Woatan. The Longobards spelt it Wôdan or Guôdan, the Old Saxons Wuodan, Wôdan, but in Westphalia again with the g prefixed, Guôdan, Gudan, the Anglo-Saxons Wôdan, the Frisians Wêda from the propensity of their dialect to drop a final n, and to modify ô even when not followed by an i. (1) The Norse form is Oðinn, in Saxo Othinus, in the Faröe isles Ouvin, gen Ouvans, acc. Ouvan. …It can scarcely be doubted that the word is immediately derived from the verb OHG. watan wuot, ON. vaða [to wade through, to rush], ôð [óðum - rapidly, vehemently]; …the ON. óðr [frantic, mad, furious, eager or mind, song, poetry] has kept to the one meaning of mens or sensus. (3) According to this, Wuotan, Oðinn would be the all-powerful, all-penetrating being, qui omnia permeat; as Lucan says of Jupiter: Est quodcunque vides, quocunque moveris, the spirit-god.Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology, ch. 29:

How early this original meaning may have got obscured or extinguished, it is impossible to say. Together with the meaning of wise and mighty god, that of the wild, restless, vehement, must also have prevailed, even in the heathen time. The christians were the better pleased, that they could bring the bad sense into prominence out of the name itself. In the oldest glosses, wôtan is put for tyrannus, herus malus; so wüeterich, wüterich is used later on, and down to the present day. …The form wuotunc seems not to differ in sense; an unprinted poem of the 13th century says 'Wüetunges her' apparently for the 'wütende heer', the host led as it were by Wuotan; and Wuotunc is likewise a man's name in OHG., Wôdunc. The former divinity was degraded into an evil, fiendish, bloodthirsty being, and appears to live yet as a form of protestation or cursing in exclamations of the Low German people, as in Westphalia: O Woudan, Woudan!; and in Mecklenburg: Wod, Wod!

I have already affirmed a connexion between this wütende heer and Wuotan, the god being linked with it in name as in reality. An unprinted poem of Rüdiger von Munir contains among other conjuring formulas 'bî Wuotunges her.' Wuotunc and Wuotan are two names of one meaning. Wuotan, the god of war and victory, rides at the head of this aërial phenomenon; when the Mecklenburg peasant of this day hears the noise of it, he says 'de Wode tüt (zieht),' Adelung sub v. wüthen; so in Pomerania and Holstein, 'Wode jaget,' Wodan hunts. Wuotan appears riding, driving, hunting, as in Norse sagas, with valkyrs and einheriar in his train; the procession resembles an army. Full assurance of this hunting Wode's identity with the heathen god is obtained from parallel phrases and folktales in Scandinavia. The phenomenon of howling wind is referred to Oðin's wagon, as that of thunder is to Thôr's. On hearing a noise at night, as of horses and carts, they say in Sweden 'Oden far förbi' (‘Odin fares nearby’). In Schonen an uproar produced perhaps by seafowl on November and December evenings is called Odens jagt, Odin’s Hunt. In Thuringia, Hesse, Franconia, Swabia, the traditional term is 'das wütende heer,' (‘furious host’) and it must be one of long standing: the 12th century poet of the Urstende uses 'daz wuetunde her' of the Jews who fell upon the Saviour; in Rol. 204, 16 Pharaoh's army whelmed by the sea is 'sîn wôtigez her,' in Stricker 73b 'daz wüetunde her'; Reinfr. v. Brnswg. 4b 'daz wüetende her'; Mich. Beheim 176, 5 speaks of a 'crying and whooping (wufen) as if it were das wutend her'; the poem of Henry the Lion (Massm. denkm. p. 132) says, 'then came he among daz wöden her, where evil spirits their dwelling have.' Geiler v. Keisersperg preached on the wütede or wütische heer. H. Sachs has a whole poem on the wütende heer, Agricola and Eiering relate a Mansfeld legend. It is worth noticing, that according to Keisersperg all who die a violent death 'ere that God hath set it for them,' and according to Superst. I, 660 all children dying unbaptized, come into the furious host to Holda, Berhta and Abundia, just as they turn into will o' wisps: as the Christian god has not made them his, they fall to the old heathen one. This appears to me to have been at least the original course of ideas.

…In Lower Saxony and Westphalia this Wild Hunter is identified with a particular person, a certain semi-historic master of a hunt. The accounts of him vary. Westphalian traditions call him Hackelbärend, Hackelbernd, Hackelberg, Hackelblock. This Hackelbärend was a huntsman who went a hunting even on Sundays, for which desecration he was after death (like the man in the moon) banished into the air, and there with his hound he must hunt night and day, and never rest. Some say, he only hunts in the twelve nights from Christmas to Twelfth-day; others, whenever the storm-wind howls, and therefore he is called by some the jol-jäger (from yawling, or Yule?). Once, in a ride, Hackelberg left one of his hounds behind in Fehrmann's barn at Isenstädt (bpric. Minden). There the dog lay a whole year, and all attempts to dislodge him were in vain. But the next year, when Hackelberg was round again with his wild hunt, the hound suddenly jumped up, and ran yelping and barking after the troop. Two young fellows from Bergkirchen were walking through the wood one evening to visit their sweethearts, when they heard a wild barking of dogs in the air above them, and a voice calling out between 'hoto, hoto!' It was Hackelblock the wild hunter, with his hunt. One of the men had the hardihood to mock his 'hoto, hoto.' Hackelblock with his hounds came up, and set the whole pack upon the infatuated man; from that hour not a trace has been found of the poor fellow. This in Westphalia.

…I am disposed to pronounce the Westphalian form Hackelberend the most ancient and genuine. An OHG. hahhul [Goth. hakuls], ON. hökull m. and hekla f., AS. hacele f., means garment, cloak, cowl, armour; (25) hence hakolberand is OS. for a man in armour, conf. OS. wâpanberand (armiger), AS. æscberend, gârberend, helmb., sweordb. (Gramm. 2, 589). And now remember Oðin's dress: the god appears in a broad-brimmed hat, a blue and spotted cloak (hekla blâ, flekkôtt); hakolberand is unmistakably an OS. epithet of the heathen god Wôdan, which was gradually corrupted into Hackelberg, Hackenberg, Hackelblock. …That the wild hunter is to be referred to Wôdan, is made perfectly clear by some Mecklenburg legends.

Often of a dark night the airy hounds will bark on open heaths, in thickets, at cross-roads. The countryman well knows their leader Wod, and pities the wayfarer that has not reached his home yet; for Wod is often spiteful, seldom merciful. It is only those who keep in the middle of the road that the rough hunter will do nothing to, that is why he calls out to travellers: 'midden in den weg!'

A peasant was coming home tipsy one night from town, and his road led him through a wood; there he hears the wild hunt, the uproar of the hounds, and the shout of the huntsman up in the air: 'midden in den weg!' cries the voice, but he takes no notice. Suddenly out of the clouds there plunges down, right before him, a tall man on a white horse. 'Are you strong?' says he, 'here, catch hold of this chain, we'll see which can pull the hardest.' The peasant courageously grasped the heavy chain, and up flew the wild hunter into the air. The man twisted the end round an oak that was near, and the hunter tugged in vain. 'Haven't you tied your end to the oak?' asked Wod, coming down. 'No,' replied the peasant, 'look, I am holding it in my hands.' 'Then you'll be mine up in the clouds,' cried the hunter as he swung himself aloft. The man in a hurry knotted the chain round the oak again, and Wod, could not manage it. 'You must have passed it round the tree,' said Wod, plunging down. 'No,' answered the peasant, who had deftly disengaged it, 'here I have got it in my hands.' 'Were you heavier than lead, you must up into the clouds with me.' He rushed up quick as lightning, but the peasant managed as before. The dogs yelled, the waggons rumbled, and the horses neighed overhead; the tree crackled to the roots, and seemed to twist round. The man's heart began to sink, but no, the oak stood its ground. 'Well pulled!' said the hunter, 'many's the man I've made mine, you are the first that ever held out against me, you shall have your reward.' On went the hunt, full cry: hallo, holla, wol, wol! The peasant was slinking away, when from unseen heights a stag fell groaning at his feet, and there was Wod, who leaps off his white horse and cuts up the game. 'Thou shalt have some blood and a hindquarter to boot.' 'My lord,' quoth the peasant, 'thy servant has neither pot nor pail.' 'Pull off thy boot,' cries Wod. The man did so. 'Now walk, with blood and flesh, to wife and child.' At first terror lightened the load, but presently it grew heavier and heavier, and he had hardly strength to carry it. With his back bent double, and bathed in sweat, he at length reached his cottage, and behold, the boot was filled with gold, and the hindquarter was a leathern pouch full of silver. Here it is no human hunt-master that shows himself, but the veritable god on his white steed: many a man has he taken up into his cloudy heaven before. The filling of the boot with gold sounds antique.

ODIN'S WIFE

THE MISTRESS OF THE WILD HUNT

Alongside Woden, we also find a woman riding at the head of the Furious Host. She is most often portrayed as his wife, Frau Gode (Gauden, Woden) or Mrs. Odin.

Jakob Grimm's Teutonic Mythology, ch. 29:

There was once a rich lady of rank, named frau Gauden; so passionately she loved the chase, that she let fall the sinful word, 'could she but always hunt, she cared not to win heaven.'' Four and twenty daughters had Dame Gauden, who all nursed the same desire. One day, as mother and daughters, in wild delight, hunted over woods and fields, and once more that wicked word escaped their lips, that 'hunting was better than heaven,' lo, suddenly before their mother's eyes the daughters' dresses turned into tufts of fur, their arms into legs, and four and twenty bitches bark around the mother's hunting-car, four doing duty as horses, the rest encircling the carriage; and away goes the wild train up into the clouds, there betwixt heaven and earth to hunt unceasingly, as they had wished, from day to day, from year to year. They have long wearied of the wild pursuit, and lament their impious wish, but they must bear the fruits of their guilt till the hour of redemption come. Come it will, but who knows when?

During the Twelves (for at other times we sons of men cannot perceive her) frau Gauden directs her hunt toward human habitations; best of all she loves on the night of Christmas eve or New Year's eve to drive through the village streets, and wherever she finds a street-door open, she sends a dog in. Next morning a little dog wags his tail at the inmates, he does them no other harm but that he disturbs their night's rest by his whining. He is not to be pacified, nor driven away. Kill him, and he turns into a stone by day, which, if thrown away, comes back to the house by main force, and is a dog again at night. So he whimpers and whines the whole year round, brings sickness and death upon man and beast, and danger of fire to the house; not till the twelves come round again does peace return to the house. Hence all are careful in the twelves, to keep the great house-door well locked up after nightfall; whoever neglects it, has himself to blame if frau Gauden looks him up. That is what happened to the grandparents of the good people now at Bresegardt. They were silly enough to kill the dog into the bargain; from that hour there was no 'säg und täg' (segen bless, ge-deihen thrive), and at length the house came down in flames. Better luck befalls them that have done dame Gauden a service. It happens at times, that in the darkness of night she misses her way, and gets to a cross-road. Cross-roads are to the good lady a stone of stumbling: every time she strays into such, some part of her carriage breaks, which she cannot herself rectify. In this dilemma she was once, when she came, dressed as a stately dame, to the bedside of a labourer at Boeck, awaked him, and implored him to help her in her need. The man was prevailed on, followed her to the cross-roads, and found one of her carriage wheels was off. He put the matter to rights, and by way of thanks for his trouble she bade him gather up in his pockets sundry deposits left by her canine attendants during their stay at the cross-roads, whether as the effect of great dread or of good digestion. The man was indignant at the proposal, but was partly soothed by the assurance that the present would not prove so worthless as he seemed to think; and incredulous, yet curious, he took some with him. And lo, at daybreak, to his no small amazement, his earnings glittered like mere gold, and in fact it was gold. He was sorry now that he had not brought it all away, for in the daytime not a trace of it was to be seen at the cross-roads. In similar ways frau Gauden repaid a man at Conow for putting a new pole to her carriage, and a woman at Göhren for letting into the pole the wooden pivot that supports the swing-bar: the chips that fell from pole and pivot turned into sheer glittering gold. In particular, frau Gauden loves young children, and gives them all kinds of good things, so that when children play at fru Gauden, they sing:

fru Gauden hett mi'n lämmken geven,

darmitt sall ik in freuden leven.

"Frau Goden, a little lamb, has given me,

so that I may live happily."

Nevertheless in course of time she left the country; and this is how it came about. Careless folk at Semmerin had left their street-door wide open one St. Silvester night; so on New-year's morning they found a black doggie lying on the hearth, who dinned their ears the following night with an intolerable whining. They were at their wit's end how to get rid of the unbidden guest. A shrewd woman put them up to a thing: let them brew all the house-beer through an 'eggshell.' They tried the plan; an eggshell was put in the tap-hole of the brewing-vat, and no sooner had the 'wörp' (fermenting beer) run through it, than dame Gauden's doggie got up and spoke in a distinctly audible voice: 'ik bün so old as Böhmen gold, äwerst dat heff ik min leder nicht truht, wenn man 't bier dorch 'n eierdopp bruht,' after saying which he disappeared, and no one has seen frau Gauden or her dogs ever since.

This story is of a piece with many other ancient ones. In the first place, frau Gauden resembles frau Holda and Berhta, who likewise travel in the 'twelves,' who in the same way get their vehicles repaired and requite the service with gold, and who finally quit the country. Then her name is that of frau Gaue, frau Gode, frau Wode who seems to have sprung out of a male divinity Mrs. Woden, a matter which is placed beyond doubt by her identity with Wodan the wild hunter. The very dog that stays in the house a year, Hakelberg's as well as frau Gauden's, is in perfect keeping.

…In the Harz the wild chase thunders past the Eichelberg with its 'hoho' and clamour of hounds. Once when a carpenter had the courage to add to it his own 'hoho,' a black mass came tumbling down the chimney on the fire, scattering sparks and brands about the people's ears: a huge horse's thigh lay on the hearth, and the said carpenter was dead. The wild hunter rides a black headless horse, a hunting whip in one hand and a bugle in the other; his face is set in his neck, and between the blasts he cries 'hoho hoho;' before and behind go plenty of women, huntsmen and dogs. At times, they say, he shews himself kind, and comforts the lost wanderer with meat and drink.

… But in Swabia, in the 16th century they placed a spectre named Berchtold at the head of the wütende heer, they imagined him clothed in white, seated on a white horse, leading white hounds in the leash, and with a horn hanging from his neck. This Berchtold we have met before: he was the masculine form of white-robed Berhta, who is also named Prechtölterli.

Here we get a new point of view. Not only Wuotan and other gods, but heathen goddesses too, may head the furious host: the wild hunter passes into the wood-wife, Wôdan into frau Gaude. Of Perchtha touching stories are known in the Orla-gau. The little ones over whom she rules are human children who have died before baptism, and are thereby become her property. By these weeping babes she is surrounded (as dame Gaude by her daughters), and gets ferried over in the boat with them. A young woman had lost her only child; she wept continually and could not be comforted. She ran out to the grave every night, and wailed so that the stones might have pitied her. The night before Twelfth-day she saw Perchtha sweep past not far off; behind all the other children she noticed a little one with its shirt soaked quite through, carrying a jug of water in its hand, and so weary that it could not keep up with the rest; it stood still in trouble before a fence, over which Perchtha strode and the children scrambled. At that moment the mother recognised her own child, came running up and lifted it over the fence. While she had it in her arms the child spoke: 'Oh how warm a mother's hands are! but do not cry so much, else you cry my jug too full and heavy, see, I have already spilt it all over my shirt.' From that night the mother ceased to weep: so says the Wilhelmsdorf account. At Bodelwitz they tell it somewhat differently: the child said, 'Oh how warm is a mother's arm,' and followed up the request 'Mother, do not cry so' with the words 'You know every tear you weep I have to gather in my jug.' And the mother had one more good hearty cry. Fairy tales have the story of a little shroud drenched with tears, and the Danish folktale of Aage and Else makes flowing tears fill the coffin with blood; but here we have the significant feature added of the children journeying in Perchta's train. The jug may be connected with the lachrymatories found in tombs.

With Berchta we have also to consider Holda, Diana and Herodias. Berchta and Holda show themselves, like frau Gaude, in the 'twelves' about New-year's day. Joh. Herolt, a Dominican, who at the beginning of the 15th cent. wrote his Sermones discipuli de tempore et de sanctis, says in Sermo 11: “There are some who say, that during the 12 nights the goddess, Diana, which some call in the vernacular 'die Frawen unhold,' walks with her army.” The same nocturnal perambulation is spoken of in the passages about Diana, Herodias and Abundia. …Berhta-worship in the Salzburg country became a popular merrymaking, so a Posterli-hunt, performed by the country-folk themselves on the Thursday before Christmas, is become an established custom in the Entlibuch. The Posterli is imagined to be a spectre in the shape of an old woman or she-goat. In the evening the young fellows of the village assemble, and with loud shouts and clashing of tins, blowing of alp-horns, ringing of cow-bells and goat-bells, and cracking of whips, tramp over hill and dale to another village, where the young men receive them with the like uproar. One of the party represents the Posterli, or they draw it in a sledge in the shape of a puppet, and leave it standing in a corner of the other village; then the noise is hushed, and all turn homewards. At some places in Switzerland the Sträggele goes about on the Ember-night, Wednesday before Christmas, afflicting the girls that have not finished their day's spinning. Thus Posterli and Sträggele resemble to a hair both Berhta and Holda. …In Thuringia the furious host travels in the train of frau Holla. At Eisleben and all over the Mansfeld country it always came past on the Thursday in Shrove-tide; the people assembled, and looked out for its coming, just as if a mighty monarch were making his entry. In front of the troop came an old man with a white staff, the trusty Eckhart, warning the people to move out of the way, and some even to go home, lest harm befall them. Behind him, some came riding, some walking, and among them persons who had lately died. One rode a two-legged horse, one was tied down on a wheel which moved of itself, others ran without any heads, or carried their legs across their shoulders. A drunken peasant, who would not make room for the host, was caught up and set upon a high rock, where he waited for days before he could be helped down again. Here frau Holda at the head of her spirit-host produces quite the impression of a heathen goddess making her royal progress: the people flock to meet and greet her, as they did to Freyr or Nerthus. Eckhart with his white staff discharges the office of a herald, a chamberlain, clearing the road before her. Her living retinue is now converted into spectres.

| CONCLUSION |

… If we now review the entire range of German and Scandinavian stories about the Furious Host, the following facts come to the front. The myth exhibits gods and goddesses of the heathen time. Of gods: Wuotan, and perhaps Frey, if I may take 'Berhtolt' to mean him. We can see Wuotan still in his epithets of the cloaked, the bearded, which were afterwards misunderstood and converted into proper names. …We see both the name and the meaning [m. or f.] fluctuate between Frau Wôdan and Frau Gôda. A goddess commanding the host, in lieu of the god, is Holda, his wife in fact. I am more and more firmly convinced, that 'Holda' can be nothing but an epithet of the mild 'gracious' Frigga; Frekka. And Berchta, the shining, is identical with her too; …The dogs that surround the god's airy chariot may have been Wuotan's wolves setting up their howl.

…These divinities present themselves in a twofold aspect. Either as visible to human eyes, visiting the land at some holy tide, bringing welfare and blessing, accepting gifts and offerings of the people that stream to meet them. Or floating unseen through the air, perceptible in cloudy shapes, in the roar and howl of the winds, carrying on war, hunting or the game of ninepins, the chief employments of ancient heroes: an array which, less tied down to a definite time, explains more the natural phenomenon. I suppose the two exhibitions to be equally old, and in the myth of the wild host they constantly play into one another. The fancies about the Milky Way have shown us how ways and wagons of the gods run in the sky as well as on the earth.

With the coming of Christianity the fable could not but undergo a change. For the solemn march of gods, there now appeared a pack of horrid spectres, dashed with dark and devilish ingredients. Very likely the heathen themselves had believed that spirits of departed heroes took part in the divine procession; the christians put into the host the unchristened dead, the drunkard, the suicide, who come before us in frightful forms of mutilation. The 'holde' goddess turns into an 'unholde,' still beautiful in front, but with a tail behind. So much of her ancient charms as could not be stripped off was held to be seductive and sinful: and thus was forged the legend of the Venus-mount. Their ancient offerings too the people did not altogether drop, but limited them to the sheaf of oats for the celestial steed, as even Death (another hunter) has his bushel of oats found him.

[HOME]

ODIN'S WIFE:

Mother Earth in Germanic Mythology